Business

Their Double Life

For many Indian Americans pursuing their "dream" career is either not practical, or not something they would love full-time. Instead, they pursue their passion part time or as a hobby. One job provides financial security, the other fulfills a passion.

|

Saira Rao was the kind of law student destined for a successful legal career. Several years spent prior to law school as a news producer gave Rao the confidence to speak up in the notoriously intimidating law school environment. Good grades helped her land a prestigious appellate clerkship on the Third Circuit after graduation. Rao settled into an office at one of New York City’s top law firms with an expansive view of downtown Manhattan.

From the outside, her life was enviable. Rao, however, quickly had a revelation about her legal career: not only was she dispassionate about the law, she didn’t feel that she was particularly good at it, either. It’s hard to know whether her perceived workplace failures stemmed from a lack of talent as opposed to a lack interest in the law. Regardless, Rao knew that she had to make a change. “I knew that the law wasn’t right for me, but it’s hard to contemplate a career change after investing so much money and time into a chosen profession,” she says. Though it took her over two and half years to leave her firm, it took nearly seven years for her to realize a dream she had secretly nurtured. “I knew for years that I wanted to write a novel, but it seemed like I never had the perfect idea, the right amount of time, or perhaps the courage to start on an entirely new track,” she says. Ironically, it was Rao’s exposure to the legal system that inspired her first novel that debuted this past summer, titled Chambermaid. The novel follows protagonist Sheila Raj, a recent graduate of South Asian decent from a top law school, to her clerkship for a notoriously mean-spirited judge. The premise seems autobiographical, although Saira maintains that the story was collectively inspired by the experiences of many clerks she met while working for her judge. She wrote the novel’s first draft after taking a position at her firm with fewer hours, giving her time to write, though she admits it was hard to cut back at work. “I knew taking myself off of ‘partner’ track at the firm would give me the chance to pursue what I love, but I still found it hard to actually take that plunge. Just being a lawyer meant I had already succeeded, but writing a first novel meant I had to confront the possibility of failure,” she says.

Now touring across country for Chambermaid and planning a second book, Rao has successfully transitioned from the law to writing. But fellow author Cathy Stocker is not surprised by young adults, like Rao, who never pursue their dream careers. Stocker’s research shows that high-achieving students are often dissatisfied at work, particularly in entry-level positions, but often don’t know how to find a career they are passionate about. As co-author of the Quarterlife Crisis Companion, Stocker has researched the dissatisfaction many adults feel with their jobs and devised practical tools to help people find passion at work. According to her research, one of the main sources of career discontent for high-achieving students is that happiness is unlikely to accompany the most prestigious and lucrative professions. Though it may seem obvious, some of the most vocal complaints of dispassionate employees come from professions like finance and law, where Indian Americans are well-represented. Outsiders have a hard time empathizing with the complaints, believing that money fairly compensates for the work.

She also notes that with college and graduate school admissions more competitive than ever, children are raised not only to be good students, but also community volunteers and enthusiastic hobbyists. “Employers demand resumes that include years of mentoring children and playing an instrument, so it’s not surprising that employees are confused, and ultimately disheartened, when they find that their job allots no time for pursuit of these commitments outside of work.” For some adults, however, the search for a fulfilling career is less about getting off the beaten career track to discover a passion and more about fighting to keep an interest alive. Rising R&B singer Ranjini Ettigi trained in classical Indian song and dance with lessons from her mother during her childhood in Richmond, Va. Singing onstage in a high-musical, however, Ettigi was struck by her overwhelming desire to pursue singing professionally. “I was so nervous before I got onstage, but as soon as the spotlight turned on, the anxiety disappeared and I was so happy. The nervousness was replaced by the realization that I loved performing enough to make it my life.” Her family, however, was adamant that Ettigi delay plans to enter the entertainment industry until after college. She soon found herself a freshman at New York University. It was Ettigi’s unhappiness with college, however, that caught the interest of a fellow passenger she sat next to on a flight during spring break. The casual conversation quickly turned to Ettigi’s passion for singing. The passenger was friends with music producer Quincy Patrick of Qwilite Entertainment and offered to put her in touch. Ettigi didn’t hesitate to audition: “I thought that the chance of meeting someone on a flight like this was a sign that I should take a chance on pursuing what I really love.”

A successful audition led Ettigi to join an all-female singing group that eventually led to a solo career now headed toward the release of her debut album. Ettigi left NYU after two years of college, but says that her parents are fully supportive of her career. “Our community stresses conventional education and careers which works for a lot of people, but it just wasn’t right for me. I know that I can always go back to the school but that the chance to create a singing career was now or never,” Ettigi says in hindsight, satisfied with her decision. For some Indian Americans, however, satisfying the parental expectation of college and even graduate studies contributes to the pursuit of their passion, or at least diminish the risks. Maulik Pancholy an Indian American actor with roles on Showtime’s black comedy hit Weeds and NBC’s primetime 30 Rock, says he knew from a young age that acting was his passion. Nevertheless, his parents encouraged him to acquire “practical” skills at college, so he majored in business at Northwestern University. After graduation, Pancholy found steady, lucrative acting work in Los Angeles, but decided to take a break and enroll as a graduate student at the Yale School of Drama. At the time, Pancholy believed that it was essential to professionally train in his chosen craft, though on reflection he acknowledges a slight cultural significance to his enrollment as well. “I never thought about my time at Yale this way, but a small element may have been the desire to satisfy some cultural requirement of graduate education. My parents were always comfortable with my decision to be an actor, but I think that going to school subconsciously showed how committed I was to the profession,” he says. LEADING A DOUBLE LIFE

For many Indian Americans, however, pursuing their “dream” career is either not practical, or something they would love if they worked on it full-time. Instead, they pursue their passion part time or as a hobby. One job provides financial security, the other fulfills a passion. Sometimes, the dual careers offer ways to blend two diverse interests instead of forsaking one. Marci Alboher, a columnist for the small business section of the New York Times and author of One Person/Multiple Careers: A New Model for Work/Life Success, has coined the terms “slashers” for the people balancing multiple careers. Slashers are all around us, Marci notes: it is commonplace for modern entertainment moguls to sing, act, and design fashion lines. Prominent members of the Indian American community like Sanjay Gupta and Atul Gawande have active medical practices balanced with their television and writing careers, respectively. “Slashers are a personality type,” Marci says, noting that many of the subjects in her book had always excelled at multiple tasks. “They are often the kids in school that could not only be good students, but also be active on school council and play a sport or instrument,” she says. The profiles in her book range from a police officer/landscaper to a Baptist minister/lawyer that can inspire readers to recognize that choosing a profession does not necessarily signal the end of hobbies or passions. Instead, this personality type likely fares better by having multiple outlets, avoiding the “burnout” that results from an intense, singularly focused career. Darshak Sanghavi is a typical slash story. The Johns Hopkins and Harvard-trained pediatric cardiologist is currently assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center. He also regularly contributes to the New York Times, Parents Magazine, NPR’s “All Things Considered,” and the Today Show – and has a critically acclaimed book to boot. His resume may be the cause of professional envy, but ironically Sanghavi never intended to be writer. Instead, he explains that he fell into the profession by accident in 1997, during his first year of medical residency in Boston. He became interested in what he considered the inadequate reporting on the medical aspects of the trial of a British au pair accused and eventually convicted of killing an eight-month old baby in her charge. When the media didn’t get the medical facts right, he decided to tackle the story himself.

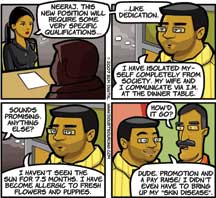

Sanghavi published his article in small journal and began to write more regularly. Later, a chance meeting with an agent led to an unanticipated book deal, which in turn led to more high-profile assignments. Ultimately, the willingness to indulge his curiosity uncovered a latent interest-and talent- in writing. He now balances his medical practice with time dedicated to writing, a special employment arrangement that was created for him enthusiastically by the University of Massachusetts Medical Center. Like other slashers, however, Sanghavi had to search for an employer that would allow him to balance his medical career with time for writing; some medical centers scoffed at the idea. “Some medical centers were only interested in medical research scholarship, not health journalism, so it was a matter of finding the right environment where they were excited to support my writing openly,” he says. In his current job, Mondays are dedicated solely to writing. Alboher says that this is a valuable lesson for slashers: sometimes the ability to pursue multiple career interests comes at the expense of getting off the fast track of their primary career or sacrificing elements of prestige. “You don’t find a lot of company CEO’s leading a slash life for a reason,” Alboher says. Careers that require a singular focus and time dedication do not have the flexibility necessary to lead a second career on the side, though she is careful to note that this does not preclude people pursuing traditional “power careers” such as medicine, law, or finance from leading a slash life. “Medicine is actually a great slash profession since many of the specialties have ‘shift’ work where the hours are fixed in advance, allowing for people to have control over their time off,” Alboher says. Consulting is another profession well suited to the slash life since it often allows for project-based work that provides a measure of independence. Sandeep Sood, co-creator of popular Badmash and new Doubtsourcing online comic strips supports his creations with bcm, a design and development firm based in San Francisco and Chandigarh. Despite the success of Badmash and Doubtsourcing, Sood never intended to pursue comic strip creation full-time, but like many slashers, enjoys having a flexible career so that he can devote enough time to watch it thrive.

Other professions popular with Indian Americans, like finance and law, are only now beginning to accommodate slashers. “These fields have lagged behind medicine in some ways because of the inflexibility of billable hour requirements and client demands,” Alboher says. But she notes that slashers reap the rewards of new part-time and telecommuting arrangements that working mothers demanded a decade ago from these traditional professions, allowing for more reduced work schedules. In fact, women in general are more likely to practice slash careers because they are used to non-linear career paths, Alboher notes. “Women tend to see careers as having periods of time when things are revved up and other times that cool down, often because of family, and therefore they gravitate more naturally to slash careers.” At its core, leading a slash life is one way people can add passion to their careers, but it may also mean reducing hours at the firm or in the research lab to make room for a second career. The arrangement can threaten chances of making partner or chief researcher. For a community full of high-achievers accustomed to continually climbing the ladder of success, it can be hard to step off. But you should trust your instinct, says Navin Kulsheshtra, founder of the visual communications company Devi Studios. He had always dreamed of being a doctor, but knew after spending semesters of college Johns Hopkins that a life of science was not for him. “I knew it was not right for me, but trusted my gut and withdrew my medical school applications,” he says. The decision was in many ways hardest on his mother, who like many Indian parents, valued the stability associated with the medical profession. “I knew, though, from my years at the research lab that being a doctor wouldn’t allow me to travel and that was a priority for me.”

The honesty with himself paid off. He learned to create websites as a mobile way to support his travels across the world. He recently founded Devi Studios as a website design company that also supports his budding documentary filmmaking career and pays off his master’s degree debt. He lived off a small budget and sought out a community of like-minded friends that encouraged him along the way. His mother is now the studio’s proudest supporter. “I couldn’t be happier,” Kulsheshtra says, “when I realized that the answer to career happiness was having the courage to trust that voice inside my head that said to follow my dreams.”

|

You must be logged in to post a comment Login