Magazine

The White Complex

What's behind the Indian prejudice for fair skin?

|

Is this fair?

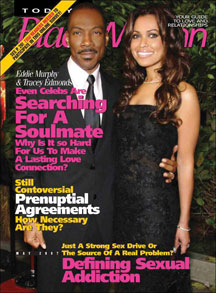

Shah Rukh Khan, the undisputed Bollywood King and role model for millions in India, is touting Fair and Handsome, a whitening cream from Emami for men in commercials that hit the market this month. King Khan, whose charisma could sell just about anything to anyone, is telling hordes of young people in India and the Diaspora, most of them dark skinned, that fairness is somehow crucial to success. Well, at least one can say that racial stereotypes are now genderless, an equal opportunity offender! For decades South Asian women have been drilled with the message that fairness equates to beauty and that a whiter complexion is key to getting ahead in life, in marriage and at work. Since 1978, Hindustan Unilever’s Fair & Lovely has sold its magic potion to millions of women, monopolizing a majority share of the skin whitening market in India, which is growing at a steady clip of 10-15 per cent per year. Several cosmetic companies have jumped on the bandwagon, including Emami, Nivea, Ponds, Garnier, the Body Shop, Jolen, Avon, L’Oreal, Lancome, Yves Saint-Laurent, Clinique, Elizabeth Arden, Estee Lauder, and Revlon. A recent article in The New York Times noted, “Skin-lightening products are by far the most popular product in India’s fast-growing skin care market, so manufacturers say they ignore them at their peril.”

Euromonitor International, a research firm, estimates the $318 million India market for skin care has grown by 43 percent since 2001. Didier Villanueva, country manager for L’Oreal India, told the Times that half of this market is fairness creams, with 60-65 percent of Indian women using these products daily. “I think the color bias among Indians is mostly a sexist issue,” says Aneel Karnani, associate professor of strategy at the Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan and the author of a business study on Fair & Lovely. “It is true that even men feel they need to be ‘whiter’ and Unilever does market some products targeted at men. This is probably due to racist biases from colonial times, but the bigger issue is the sexist bias. There is much greater pressure on women to be fairer, because this is society’s and men’s notion of beauty.” Indian immigrants, living far from home, seem to export their white fixation, along with their achaars, papads and Alphonso mangoes, when they migrate to the New World. “I think the color bias persists among overseas Indians, especially those who have not integrated into the local culture or society,” says Karnani. “You can easily buy Fair & Lovely in Indian shops in the U.S. and Canada, but not in mainstream shops. This bias is not unique to India as many countries in Asia and the Middle East suffer from the same bias.”

Walk down the aisles of any Indian grocery store in the U.S., and you are bound to come across an old friend – or nemesis – from India: the innocuous, very bland looking Fair & Lovely cream. It promises a fairer skin in days, and more than that, a perfect life: a sure-shot at a husband, a super job and instant acceptance. Yet one could also say it is a tube full of stereotypes, of racial undertones. Does one have to be fair to be successful or loved? The ads for the cream always depict a dark, unhappy and self-conscious woman, shut off from opportunities. The moment she starts applying the cream, she turns several shades lighter, gets the plum job and supreme self-confidence. So where did this fairness-fetish come from? It has most frequently been blamed on the British Raj and identification with the colonizers, but historians also trace the prejudice to Vedic times, when the ideals of feminine beauty included a fair skin. Miniature paintings have a rainbow of complexions, but the darker skins are of attendants and servers, while the royalty and privileged class are fair. In India’s bazaar art the mighty Gods and Goddesses, except Krishna, who is the blue-skinned, are rosy pink. Poems and shayari across the ages celebrates sangemarmar sa badan (marble-like body) and chand sa mukhda (moon-faced). “Indian culture is deeply marked by two experiences: caste and colonialism,” says Vijay Prashad, professor of South Asian Studies at Trinity College, Hartford, Conn., and author of several books including The Karma of Brown Folk. “The former, as a system, pushed down certain communities, either through untouchability or else the idea of hierarchy itself, so that even those who were not untouchables had to reckon with being seen as inferior to others.”

He adds: “Race-thinking and racism came to India via colonialism, and they marked the hreformulation of caste. In other words, when race-thinking came to India, the worst elements of caste were re-cast, as it were, on racial lines. The meaning of varna, for instance, was seen as a hreference to skin color rather than to feudal standards. European racism entered India through the hierarchy of caste; European racism ‘modernized’ the worst aspects of the caste system.” Historians, anthropologists and psychologists may well argue over the reasons, but there is no dispute that the preference for white is entrenched in the India mindset. Gori (white) is a compliment and Kalia (black) is a put down. But what is something as archaic as Fair & Lovely doing in America, land of the free, home of the liberated woman? Surely, women of South Asian origin aren’t still hooked to the mantra of white skin to solve all of life’s problems? Every Indian store Little India called all over the country stocked Fair & Lovely and some also offered a range of ayurvedic skin whitening creams as well, such as Shahnaz Husain’s Shafair and Fair One Cream, all promising a fairer skin in weeks. Indian men are now being lured with the same color motivations. The men’s fairness market is booming in India, with Hindustan Unilever (HUL) and Emami battling it out with products like Fair & Lovely’s Menz Activ and Fair and Handsome respectively. Writes Gopalkrishna Seshan in Business Standard: “When Emami was studying the market for ways to break HUL’s stranglehold on the fairness products market – HUL’s Fair & Lovely has been the undisputed market leader since its launch in the 1970s – it experienced an epiphany: over a third of Fair & Lovely’s customers were men.” It is to capitalize on this large hidden market that Emami has come up with Fair and Handsome, a $10 million brand, which is reputed to be growing at 25 percent a year.

So now the Indian man is being held to the standards of the color code: not only is he expected to be brainy and bright – a surgeon, engineer or a call center worker at the very least – but now he has to be fair too! On its website, Fair and Handsome asks, “Why there is need for fair skin?” The answer, it says, “To look attractive, else not good looking, people will not want to talk, it affects our confidence.” Khubsoorti hai shakti (Beauty is strength) is the slogan of many of these whitening creams, but of course, beauty is code for a fair skin. The men’s product tagline is Badal do apni kahani (change your story) and here too it’s a whitening agent that helps transform destiny. The ads are a bit over the top, as darkish stuntmen become star heroes once they use the cream and simple, cowering women transform into self-confident divas astride jets as the paparazzi go wild with their cameras. Given the surging demand, scores of imitators of Fair & Lovely have cropped up in India: Fair & Natural, Fair & Sweet, Famous & Beauty, Famous & Lovely, Face and Lovely, Fure & Beauty, Fair & Care, Fairy & Lovely, Fain & Lovely, Fresh Look, Fine Love. Hindustan Lever even offers Fair & Lovely Body Fairness Milk, which takes care of the entire body and “its gentle formulation gives fairness all year round.” No point in having a fair face if the rest of your body is dark. The color preference seems to cut across the country’s geography. Even South Indians, who are darker than North Indians, show a distinct bias toward fairness. Most of the top heroines in Southern cinema, Hema Malini, Vijayantimala and Sridevi, are fair. All the great heroes, MGR, NTR as well as the current hot favorite Rajnikant, are fairer than their audience.

Since the fairness complex is so deeply entrenched in the Indian psyche, it is no surprise that profiles on popular Indian matrimonial website, such as Bharatmatrimony.com or Shaadi.com, almost uniformly paint women as fair – or, at the very least, “wheatish” in complexion. All want a partner who is very fair, fair, wheatish or wheatish medium – whatever that is! It is the rare individual who elects “doesn’t matter” when selecting the choice of complexion in a preferred partner. Still, almost no one admits to being dark. Roksana Badruddoja Rahman of Rutgers University, who studied skin color and marriage choices among Indian women in New Jersey, concluded that “feelings related to beauty and attractiveness and marriage marketability are partially determined by the lightness of their skin.” Another researcher, Zareen Grewal of the University of Michigan, similarly found that South Asian immigrants covet whiteness: “Particular physical qualities are always fetishized in constructions of beauty. However, in these communities, the stigma attached to dark color intersects with broader racial discourses in the U.S. That’s why a Desi mother of three daughters in their twenties, explicitly hrefers to dark coloring as a physical abnormality and deficiency.’ Atleast one such “dark and ugly” bride became a cause celebre in the U.S. media last year. Vijai Pandey of Belchertown, Mass., who traveled to India to meet a prospective bride, judged her too ugly and dark for his handsome and light-skinned son. He sued her U.S. relative for fraud and conspiracy for misleading him about her looks and complexion! In the Indian media you’ll be hard-pressed to find a dark face, be it in an ad for cell phones, bridal fashions or insurance. Everyone is fair or pleasantly “wheatish.” In Indian television serials, so hugely popular in India and now a staple in the U.S., everyone from daughters-in-law to mothers-in-law, not to mention children and male family members, is extremely fair. They all must be using Fair & Lovely.

Bollywood has long been obsessed with the fairness mystique. Says Anupama Chopra, a noted film journalist: “Films are a hreflection of society. So Bollywood, like much of Indian society, did believe that fair is beautiful. The heroines especially were expected to be fair, have big eyes and long hair. I recall one particularly nasty film in which Rishi Kapoor had a very dark wife. The wife actually encouraged and understood his affair with the much fairer girlfriend, because she felt she was too ugly to merit his love.” This characteristic carries over to recent films, like the hugely successful Vivah, in which the fairer girl, Amrita Rao, gets the rich, city boy, but her dark skinned cousin isn’t as fortunate. “Audiences always aspire to ape the stars, so I’m sure many women were made even more hungry for fair skin. The look of actors, however, has drastically changed. Of the contemporary leading ladies, many have dusky complexions – Kajol, Bipasha Basu, Rani Mukherjee, and Priyanka Chopra – and yet they are very successful. Only Kareena Kapoor is strikingly fair. The king of Bollywood, Shah Rukh Khan, isn’t fair at all. Neither is John Abraham or Arjun Rampal. In fact, in Dhoom 2, everyone including the very fair Hrithik Roshan and Aishwariya Rai had put on lots of tan make-up. So I don’t think color is some sort of pressing issue.” Chopra adds, “In the recently released film Hattrick, Paresh Rawal plays a London-based NRI. His daughter falls in love with an African American, which is the ultimate taboo. At first, he’s horrified but in the end, he accepts them both.”

Mira Nair explored the issue of inter-racial romance in her powerful film Mississippi Masala several years ago, building in the experiences of Indian immigrants who had lived in Kenya and Uganda before coming to the UK and the U.S. In the film, Denzel Washington plays Demetrius, a black carpet cleaner who falls in love with Mina, daughter of Indian immigrants in the motel industry. In one memorable scene, after he’s forced to break up with her because of the outrage of the Indian community, he confronts her father and states a simple fact: “Your skin is just a few shades lighter than mine.” Therein lies the crux of the matter. Many Indians, no matter their skin color, tend to perceive themselves as white. Mira Nair told Little India in an interview at the time: “This film is about the human condition. In seeing the two communities interact, I hope that the unexpected similarities will be seen and the amazing echoes from one to the other will be heard, even though the two communities rarely think of one another as similar or close. Both have preconceptions about the other, and it is my hope that they will see that it is really myopia that is the basis of so much prejudice.” Sarita Choudhury the beautiful, tawny actress who played the role of Mina in Mississippi Masala is hardly fair. She says: “I am very aware of the whole favoring of the ‘fair’ but I personally feel safe, and outside the whole issue. It is not relevant to me on any level. I think maybe because I had a mother who was a fair English lady and a father who is Bengali. As a family all color variations seemed normal, personality was more the winning factor.”

Choudhury grew up in London and Rome, where she was definitely darker than the local community. If anything, she was exoticized, which, she says, is also not a nice feeling, because you feel like “the other.” She says: “But I remember as a teenager I would go to the beach and get a tan. I would love the sparkly feeling of being healthy, but I remember the Indian community would frown on such a thing.” Choudhury, who recently starred in M. Night Shyamalan’s Lady in the Water, recalls the brouhaha when Mississippi Masala came out. “I just remember thinking how normal it was to me the whole idea of an Indian girl going out with an African American man. But when the film came out so many Indian girls came up to me and thanked me for showing a life they felt was normal, but somehow they still couldn’t explain to their communities or parents.” She adds, “I understood, because family and tradition is so dear to me even when the issues are unfair, like color of skin. You have to be so delicate in sharing your point of view with your own family…. We are not all revolutionaries.” Observes Prashad: “I think that the way anti-Black racism, or the way South Asians of certain sections easily adopt anti-Black attitudes is the best example of how the consciousness persists among overseas Indians. Hierarchies of caste are mapped onto the hierarchies of race that permeate U. S. culture. This does not mean, however, that all South Asians are anti-Black. Far from it.” He adds: “There is a considerable interchange between South Asian Americans and African Americans, not just as neighbors or in romance, but also in politics and in academia. There is an important dynamic within Asian American Studies, for instance, to seek these connections and study them. Many South Asian Americans are part of the movements that struggle for, among other things, Black liberation. Also, the women’s movement within the South Asian American community has seen the danger of color consciousness and its misogyny.”

However, ask first generation Indians living in America about race and color preferences and they tend to offer up muted, politically correct answers. A few will mention friends who worry about their daughters being too dark for the marriage market or are concerned about their own complexion if they go into the sun. A more honest and raw discussion on the dynamics of color can be found on blogs, which are the often the mirror of the soul. Not surprisingly, the topic of Fair & Lovely sparked heated debates on sites such as Sepia Mutiny and Vislumbres. One respondent noted: “How many Indians have complexions like Preity Zinta or Hrithik Roshan? How many Indians have green eyes like Aishwarya Rai? Probably less than 0.5% of Indians. If one looks at the Bombay Times, Bollywood films, or Indian models, you will notice that the paragon of beauty is that of a light-skinned person with aquiline features. Indian movie stars do not resemble the men and women on the streets of Bombay or other Indian cities. India’s movie stars look like light-skinned Iranians, Turks, or Spaniards who speak Hindi.” Another suggested that skin lightning wasn’t such a novel idea for Indian men: “A lot of men back in India, especially amongst the older generation, rub white talcum powder all over their faces in order to ‘freshen up’ when going out, with the actual intention of making their faces look lighter.” One blogger described a telling incident, which exposes the double standards of some parents: “All this talk about ‘fairness’ reminds me of a friend whose parents tried to arrange him. One of their criteria was fairness, and they obsessed over it. What is funny is my friend started dating some white girl and when his parents flipped, he said, ‘At least she is very fair.'” Yet another wrote: “I’m dark and I lived the first 18 years of my life in a part of India, where kalua/kali is considered as abuse, while my mother tried hard to make my skin lighter by slapping on sandalwood paste on my face. I’ve been in America for a year now, and here they tell me that they love my skin and they love my complexion and would kill for it. I tell them that I know that roughly a billion people in India might kill for their Caucasian skin too. I guess mankind just wants what it does not have.”

Laila Samtani, a beautician in Paramus, N.J., has seen hundreds of Indian women clients of all hues over the years at her salon. She believes attitudes are changing among Indian Americans. When she was growing up in India, it was common to bleach one’s face simply because Indian women have dark facial and body hair, which gives the skin two tones. Women’s beauty regimens always included bleach or hair removal. Now they turn to waxing, threading or laser treatment to give the skin a single tone. Samtani says the fairness fad persists among the older generation. “You will never see any youngsters or college graduates using any of that kind of stuff on their face. Nowadays the younger girls are into tanning and don’t ask about whitening creams. They are into a healthy, one tone skin. I haven’t come across any clients wanting a fairer skin. Nowadays people value what they have and as a nation, we have the best skin.” A woman who’s experienced both sides of the field is psychiatrist Dr. Vidushi Babber, currently medical director at the Institute of Neuropsychiatry in Louisiana, host of a talk show, “Winning with Wellness” on VoiceAmerica Women’s network and co-author of A Healthier You and Rising to the Top. She too finds that attitudes are changing in the Indian American community. “When I was younger it was more of an issue, but now that we’ve mixed with the American community it’s no longer an issue that people focus on much anymore. They have so many different colors and cultures in America that everyone sort of blends in just by being different.” Indian youth seem far less prejudiced: “The new generation has been accepting of people of different colors and races, because we have been more in touch with people outside of our own color and race and I think people have started to realize that it’s more than just what’s on the outside and now that we have more interaction between male and female, it’s been understood that it’s more about the personality than what you see on the outside that defines the person, not your color.” Babber doesn’t have a problem with whitening creams, but quibbles with the motivations of some people who apply them: “I think if people are using them, because society wants them to or their family wants them to, then it’s an issue. If they as individuals feel they want to be lighter, it gives them more self-confidence, if that’s something they personally want, then it’s a healthy choice to make for themselves. Otherwise it’s an unhealthy choice, because they are struggling with somebody else’s view of how they should be, a change from the outside being foisted on them.” Of course, Indians are not alone in their color biases. Creams like Fair & Lovely are doing a rip-roaring business in countries as diverse as Mexico, Malaysia, China, Brazil and Korea. Even in America, many African Americans use whitening creams, peddled euphemistically as treatments for blotchy skin and hyper-pigmentation. It’s as if the whole world has enrolled in a white seminary or madrassa to chant the virtues of fairness. Color may be just a matter of pigmentation, but cultures everywhere seem to attach a special cachet to whiteness, an almost unconscious belief in its magical power to open doors, to make life better. It will likely take generations to undo the brainwashing.

|

You must be logged in to post a comment Login