Life

The Rediscovery Of The Kamasutra

Kamasutra is not a book on positions in sexual intercourse. It is a book about the art of living -- about finding a partner, maintaining power in marriage, committing adultery, living as or with a courtesan, using drugs -- and also about the positions in sexual intercourse.

|

The greatest pleasure of revisiting an old classic is the discovery of its fresh aspects, which have been missed in an earlier, more superficial reading. This, of course, is what makes a book a classic instead of the more effervescent offerings of writers who may excite passing interest, stimulate some discussion, but are soon forgotten. This was also our experience when Wendy Doniger, the distinguished Indologist and historian of religions at the University of Chicago and I did a new translation of the Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra for the Oxford World Classics (2002). The best known earlier translation of the Kamasutra is by Richard Burton. Its first version was prepared by two Indian Sanskrit scholars Bhagwanlal Inderjit and Shivaram Bhide and the book should be rightfully known as Inderjit-Bhide-Burton translation of the Kamasutra. Burton polished the text prepared by the Indian pandits and his main contribution was less in the translation than in his courage and determination to publish the work in a sexually repressive Victorian era with its strict laws on obscenity. Widespread public knowledge of the Kamasutra, in both India and Europe began with the Burton translation of 1883 which was extensively pirated and printed in underground editions till 1962 when it was formally published in England and the United States. Burton Translation:

There are many serious flaws in the Burton translation which Doniger has detailed in our book. The text is padded in the sense that it includes passages from a much later commentary masquerading as Vatsyayana’s original text. Direct quotes are made indirect, depriving the original of its animating force. There are several mistranslations, some of which downplay the woman’s agency in the erotic enterprise, evident in the original. The translations for male and female sexual organs as lingam and yoni are inappropriate, if not blasphemous, since these terms have strong religious overtone for Hindus, referring, as they do to the sexual organs of the god Shiva and his consort Parvati. Vatsyayana, in the original, rarely uses lingam and never yoni. He prefers, instead to use such terms as jaghana (which can be translated as genital, pelvis or ‘between the thighs’) and yantra or sadhana (‘the instrument’)’. But let me leave Burton aside and move to aspects of the Kamasutra which are still highly relevant, even almost 1,700 years after the text was first composed. More than sexual intercourse:

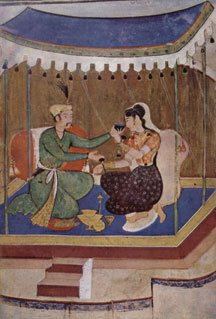

But first, one needs to clear the widespread misunderstanding that Kamasutra is a book about sexual intercourse. This impression is mostly due to the persisting emphasis on only one of the seven “books” or chapters that comprise the Kamasutra: Book Two, which discusses sexual typology, sexual positions, kissing, biting, slapping, oral and unusual sex and so on. Book Two, perhaps also because of the raunchy illustrations in innumerable versions of the Kamasutra, has overshadowed the rest of Vatsyayana’s text in the popular imagination. To put it bluntly, Kamasutra is not a book on positions in sexual intercourse. It is a book about the art of living – about finding a partner, maintaining power in marriage, committing adultery, living as or with a courtesan, using drugs – and also about the positions in sexual intercourse. The Kamasutra has attained its classical status because it is at bottom about essential unchangeable human attributes – lust, love, shyness, rejection, seduction, manipulation. Little wonder that it is the most famous textbook of one of the three principal human sciences or shastras in ancient India, kama (desire/love/pleasure/sex), the other two being dharma (duty/morality/law/ religion) and artha (money/political power/material success). These three shastras were part of every cultivated person’s education. It is sad that today, in our contentious debate over introducing sex education in schools in India, we tend to forget the vital place our ancestors accorded to the study of kama, although we must not forget, and perhaps can learn from them, that ancient sex education was not limited to matters purely sexual, but was more broadly also an education in sensuality. I cannot share all my discoveries in this limited, but will only talk of two of the most pleasant surprises as we engaged with Vatsyayana’s text. The first discovery was the Kamasutra’s treatment of woman as a subject and full participant in sexual life. The text bothreflects and fosters the woman’s enjoyment of her sexuality. Vatsyayana expressly recommends the study of Kamasutra to women, even before they reach puberty. Two of the book’s seven parts are addressed to women: the fourth to wives and sixth to courtesans. Women and Kamasutra: Woman is very much a subject in the erotic realm, not a passive recipient of the man’s lust. Of the four embraces in preliminary love play, the woman takes the active part in two. In one she encircles her lover like a vine does a tree, offering and withdrawing her lips for a kiss, driving the man wild with excitement. In the other – familiar from its sculpted representation in the temple friezes of Khajuraho – she rests one of her feet on the man’s and the other against his thigh. One arm is across his back and with the other clinging to his shoulder and neck she makes the motion of climbing him as if he was a tree. In the final analysis, though, given the fact that the text was composed by a man primarily for the education of other men, the fostering of a woman’s sexual subjectivity is ultimately in the service of an increase in the man’s pleasure. The Kamasutra recognizes that a woman who actively enjoys sex will make it much more enjoyable for him. Women in the Kamasutra are not only presented as erotic subjects, but as sexual beings with feelings and emotions which a man needs to understand for the full enjoyment of erotic pleasure. The third part of the text instructs the man on a young girl’s need for gentleness in removing her virginal fears and inhibitions. “For the first three nights after they have been joined together, the couple sleep on the ground, remain sexually continent, and eat food that has no salt or spices. Then, for seven days they bathe ceremoniously to the sound of musical instruments, dress well, dine together, attend performances, and pay their respects to their relatives. All of this applies to all the classes. During this ten-night period, he begins to entice her with gentle courtesies when they are alone together at night. The followers of Babhravya say, “If the girl sees that the man has not made conversation (i.e. sex) for three nights, like a pillar, she will be discouraged and will despise him, as if he were someone of the third nature (i.e. a homosexual).” Vatsyayana says: “He begins to entice her and win her trust, but he still remains sexually continent. When he entices her he does not force her in any way, for women are like flowers, and need to be enticed very tenderly. If they are taken by force by men who have not yet won their trust they become women who hate sex.”

Erotic pleasure demands that the man be pleasing to his partner. In recommending that the man not sexually approach the woman for the first three nights after marriage, using this time to understand her feelings, win her trust and arouse her love, Vatsyayana takes a momentous step in the history of Indian sexuality by introducing the notion of love in sex. He even goes so far as to advance the radical notion that the ultimate goal of marriage is to develop love between the couple and thus considers the love-marriage (still a rarity in contemporary Indian society), ritually considered as “low” and disapproved of in the religious texts, as the pre-eminent form of marriage. The Kamasutra is a radical advocate of women’s empowerment in a conservative, patriarchal society in other ways, too. The dharma law books of the time come down hard on women contemplating divorce: “A virtuous wife should constantly serve her husband like a god, even if he behaves badly, freely indulges his lust, and is devoid of any good qualities.” Vatsyayana, on the other hand, views the prospect of wives leaving their husbands with equanimity; he tells us that a woman who does not experience the pleasures of love may hate her man and leave him for another. He is equally subversive of the prevailing moral order between the sexes when he advises courtesans (and by extension, other women readers of the text) on how to get rid of a man she no longer wants. “She does for him what he does not want, and she does repeatedly what he has criticized… She talks about things he does not know about… She shows no amazement, but only contempt, for the things he does know about. She punctures his pride. She has affairs with men who are superior to him. She ignores him. She criticizes men who have the same faults. And she stalls when they are alone together. She is upset by the things he does for her when they are making love. She does not offer him her mouth. She keeps him away from between her legs. She is disgusted by wounds made by nails or teeth when he tries to hug her, she repels him by making a ‘needle’ with her arms. Her limbs remain motionless. She crosses her thighs. She wants only to sleep. When she sees that he is exhausted, she urges him on. She laughs at him when he cannot do it, and she shows no pleasure when he can. When she notices that he is aroused, even in the daytime, she goes out to be with a crowd. She intentionally distorts the meaning of what he says. She laughs when he has not made a joke, and when he has made a joke, she laughs about something else…..” It is not that Vatsyayana idealizes women; only that he is equally cynical about men and women as far as sex is concerned. The law books are traditionally patriarchal in discussing why women commit adultery: “Good looks do not matter to women, nor do they care about youth; ‘A man!’ they say, and enjoy sex with him, whether he is good looking or ugly.” The Kamasutra, on the other hand, is more egalitarian: “A woman desires any attractive man she sees, and, in the same way, a man desires a woman. But, after some consideration, the matter goes no further.” Eroticism: My second discovery had to do with Kamasutra’s central agenda of transforming sexuality into eroticism. Vatsyayana makes us realize that the ferocity of unchecked sexual desire can easily overwhelm erotic pleasure, a devastating loss for our humanity and the way we should lead our lives. Today, when what were once called “perversions” are normal fare of television channels, video films and internet sites, where small but specialized professions exist for the satisfaction of every sexual excess, Kamasutra’s project of rescuing the erotic from the rawly sexual would find many supporters. In today’s post-moral world, the danger to erotic pleasure is less from the icy frost of morality than from the fierce heat of instinctual desire. Kamasutra’s most valuable insight, then, is that pleasure needs to be cultivated, that in the realm of sex, nature requires culture. The Kamasutra is a classic of world literature in its singular cultivation of eroticism, in infusing sexuality with playfulness. Alone among other classics of erotica in the world, Kamasutra proclaims an ethic of the erotic, combines sense with sensuality. Mad and Divine: Spirit and Psyche in the Modern World Sudhir Kakar’s new book, Mad and Divine: Spirit and Psyche in the Modern World, to be released this summer, looks at the interplay between the psyche and spirit in the healing traditions, both Eastern and Western, religious rituals and in the lives of some extraordinary men such as Osho (Rajneesh), Gandhi and Drukpa Kunley. Kakar argues that to neglect either the spirit or psyche in understanding the person is to ignore the wholeness that makes us human. In Vatsyayana Kamasutra: A New Introduction, you speak of the richness of flexible and merged genders in all of us. We let go of our feminine sides while at times, we engage with our masculine aspects. I kept wondering what is the place for homosexuality in Kamasutra. If love is erotic, then (genital) sex should matter less. Am I right in thinking that? The Kamasutra is not independent of the Dharmashastras, but seeks harmony with it. The space for the erotic is carved out of the Dharmashastras’ territory of reproduction. Homosexuality then becomes a problem although it is very different from what we understand by homosexuality today. A homosexual in Kamasutra is anyone unable or unwilling to reproduce. You can actively engage in oral sex with the “masseur” and not be considered a homosexual. There is enormous erotic sensibility in Indian religion and later in Indian temple architecture. Does this all come from the same tradition? Or, expression of that tradition in Kamasutra allowed for a more visual, sculptural expression?

I would say both, the one feeding into the other. Are the Khajuraho temples directly inspired by Kamasutra (as some films and several books imply today) or are they more inspired by the traditions and place of sensuality, eroticism within Indian traditions? The inspiration is the high place accorded to sensuality in India at the time, but some of the actual friezes are direct representations of the sexual embraces described by the Kamasutra. Your defense and explanation of the place of women in Kamasutra is very instructive. The general impression, however is that it is still patriarchal and therefore somewhat misogynist toward women. The immigrants are often taken to be the inheritors of this great tradition of sexuality in Kamasutra. Popular culture here is replete with jokes about the assumed prowess of Indians in matters sexual. Some of that embarrasses us and films don’t quite help. Kamasutra is still the most famous Indian text in the West. Do Indians have at least theoretically and traditionally, the richest heritage in the erotics of love? As Indians and Indian immigrants, we live in two worlds about sexuality. We are still prudent in our public lives and at least in the realm of private that extends to the family, we are still rather coy and reserved. I don’t know about our deeper personal spheres. On the other hand, there is the public world of Bollywood films, the gyrating dancers, the explicitly and exhilarating erotic sculptures in spaces of religion. How do you see this chasm? How did a culture of such sensuality become so prudish and orthodox in its practice of sexuality? This is a question that requires a long answer, beginning with the dialectic of the ascetic and erotic in Indian tradition, and going on to discuss the influences of Islam and British colonial values. I would direct the interested reader to the chapter on sexuality in my book The Indians: Portrait of a People. |