Magazine

The Most Beautiful Woman In The World

When I see the way Naina looks at me i am reminded of the way i still look at my mother.

|

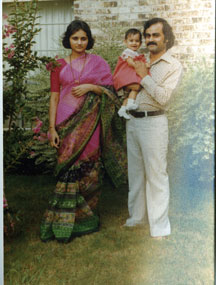

One of my most evocative childhood memories is sitting cross-legged on the edge of my parents’ bed watching my mother, Sandhya, putting on her sari before an evening party. Deftly folding the fabric still warm from my father’s expert ironing job, she would transform the long cloth into a garment. Pink, orange, gold, the intricate threadwork would catch the light as she pleated and wound the sari around her body. With a satisfied flourish she would toss the ornate pallu over her shoulder as my father, younger brother, and I admired her handiwork. Determined to help I would pick out matching bangles and a bindi. When at last she carefully positioned the bindi between her eyebrows she was ready, hopelessly glamorous, a Bollywood heroine of my very own.

The birth of my own baby girl this past July has had me pondering the unique relationship between my mother, an Indian immigrant, and myself, her daughter, born and raised here. Unfortunately, the theme of generational and cultural conflict has come to dominate Indian American explorations of female identity and familial relationships. The tired cliché of tradition versus modernity is very often played out in literature and film, particularly through the clothing choices of women. One has only to think of the common stereotype of the “Westernized” daughter who rebels against her family by hiding her tank top and miniskirt under bulky clothing, surreptitiously changing in the car before going out. Or the mother making yet another cup of chai in the kitchen dressed in a drab salwar kameez, a dupatta modestly covering her head. The prevalence of such images points to the importance of clothing as a marker of identity and belonging, but reduces mothers and daughters to ciphers of so called tradition and modernity, of East and West. As Indian American women navigate our way among the intersecting cultural norms that make up our lives as diasporic subjects, clothing and beauty rituals are one of the most powerful ways we define ourselves. Practices like threading, mehndi, or wearing a sari are not simply reproduced here in the U.S., but continue to change and evolve, as they do in India itself. Mothers do not just pass down traditions to their daughters. They involve them in a dynamic process of interpreting these practices to make them relevant to their everyday lives. Sharing in this process gives us ownership of the stylistic modes by which we perform our racial and gender identities. Growing up desi in the Bay Area in the 1980s presented certain challenges. As an Indian American girl I was bombarded with idealized images of femininity in the pages of the books and magazines I devoured (I’ll never forget the Sweet Valley High twins: tall, blond, green-eyed, “the perfect size 6”) and later from the Bollywood pop culture I became obsessed with in my teens. Nevertheless, my mother was my first and most influential model of femininity, of what it meant to be an Indian American woman.

She was always effortlessly chic even in jeans and a shirt, but when she wore Indian clothes she dazzled me. Far from being embarrassed when my mother would wear saris or salwar kameez to school functions or out to dinner, I felt like I had the most beautiful mother in the room. This perception of beauty developed my sense of what Indianness could mean: a brand of glamour and cosmopolitanism to ameliorate the provincial nature of small town America. By sharing her comfort in pulling from the sartorial traditions and stylistic sensibilities of the many cultures in which we moved, my mother imparted to me a sense of self-confidence as I shaped my own version of Indian American femininity. Part of the richness of the relationship between mother and daughter is its symbiotic nature, something I am only really beginning to understand after the birth of my own daughter, Naina. Just as a mother imparts confidence to her daughter, a daughter’s gaze, full of love and admiration, provides her mother with a renewed sense of her own intrinsic beauty. Our society is one that prizes youth above all else. Becoming a mother and turning thirty all within a span of three months, I suddenly felt old for the first time in my life. But when I see the way Naina looks at me I am reminded of the way I still look at my mother. I like to think that while she always modestly brushes off my effusive praise my mother is able to see herself through my eyes for even a moment, duniya ki sabse badi haseena — the most beautiful woman in the world. |

You must be logged in to post a comment Login