Food

The Elusive Indian Aam

India, the world’s largest mango grower, cannot seem to crack the U.S. market.

Pennsylvania-based dentist Bhaskar Savani, who has been at the vanguard of the Indian mango movement in the United States, says that for anybody who grew up in South Asia, mango is much more than just a fruit — “It’s a story, a memory.”

Well, Savani definitely has his own very compelling mango story to tell.

Bhaskar Savani with his dad whose love for mangoes prodded him to get into the mango import business.

In 2000, Savani was waiting to receive his father, who was coming from India, at JFK Airport in New York. As scores of passengers drifted by, Savani became worried about his dad’s no-show. Wondering what could have gone wrong, Savani finally spotted his dad arriving three hours late and smelling heady of mangoes.

He laughs at the recollection: “My dad used to smuggle a few mangoes from India in his luggage like many Indians would do. But this time he went overboard and decided to bring along a whole bag.

Caught by immigration officials, when he was asked to trash the fruit, he chose to eat as much of his prized possession that he could, standing right there at the airport.”

This hilarious episode drove Savani, then a full time practicing dentist, to dig deeper into the ban that stalled the journey of Indian mangoes into the United States.

Although the ban on Indian mangoes in the United States was lifted in 2007 after years of serious lobbying, in which Savani played no small part, curiously, Indian mangoes still remained a rarity in the country. The import of Indian mangoes had been banned in the United States since 1989 over concerns about pests spreading onto American crops.

Savani says: “The ban was actually more to do with the fear of competition from Indian mangoes amongst Americans involved in the trade than the stated phytosanitary reasons. But sadly, even after its overturning, Indians were scarcely able to promote and propagate their storied mangoes to America.”

Indian mangoes which are revered for their superior taste, come in a mindboggling 1,500 different varieties, each with its distinct sight, smell, characteristic and taste. India accounts for 40 percent of the world’s production of mangoes.

Most fruit experts maintain that anyone who has tasted an Indian mango would instantly know the difference between it and Latin American or other varieties around the world.

Will Cavan, executive director of the International Mango Organization, based in Vista, Calif., distinctly recollects his first Indian mango experience: “I remember, it was a hot August day in Delhi back in 1973. I had my first taste of Indian mango as a 13-year old over breakfast at the InterContinental Hotel and it was more delicious that anything. And by this point in my life I had already eaten mangoes in Colombia, Brazil, Mozambique, Taiwan, Vietnam and Thailand.” During his several later visits to India, Cavan also discovered that the love and the very special relationship that Indians have with mango is uncommon in any other culture. He says: “Even the leaves are treasured and play a ceremonial role. There are also several legends associated with the fruit and mango tree.”

Cavan who describes his nonprofit as the ombudsman for the global mango community regrets that the first attempts to plant Indian mangoes in the United States in the late 19th century were unsuccessful. He says, “The tragedy is that the trees landed in Florida’s hostile environment. If it were in the desert of California, we would be eating Indian mangoes in the U.S.”

Lovers of the fruit insist that most Americans, who have been eating the hot water ripened mangoes from South America, do not really know what they are missing out on.

Indian American Fans

Most Indians in America either flock to Indian stores as the season arrives in hopes of finding Indian mangoes, such as ratnagiri and alphonso, which sell out as fast as they arrive, or turn to online sources, such as Mangozz Online, Mangowale, Yum Mangoes and Savani Farms, an initiative run by Bhaskar Savani himself.

Savani says Indian Americans eagerly await the arrival of mangoes, which are shipped to customers soon as they arrive. In the spring of 2018, one of the first shipments of this year’s mangoes arrived from India on the East Coast. Kay Bee Exports sent across three metric tons of mangoes on a British Airways flight to its mostly Asian American clientele. The exporters are hopeful that with an increase in demand and USDA approval of three more irradiation facilities in India, it is likely that we will see more of kesar, chausa, baganpalli and alphonso mangoes in America.

But outside of the patronage it enjoys in the community, the Indian aam remains mostly undiscovered in America Ken Love, executive director, Hawaii Tropical Food Growers and a true-blue mango aficionado, admits that he has never met a mango he hasn’t liked.

Of Indian mangoes, he says, “I’ve enjoyed mangos from almost all countries where they are produced and certainly they are among the best.”

Love’s non-profit is aimed at expanding the production and diversity of Hawaii grown tropical fruits and he is working toward growing Indian mangoes in the United States. He says: “We have about 800 members statewide and our focus is on research and promotion of locally grown fruit. That said, with regards to mango, import is not something we want to see, but we recognize the desirability of the Indian mango once they are grown here. Currently we are grafting varieties like jumbo kesar, alphonso, totapuri, himayudin, malika and many others.”

Savani, after years of exporting mangoes from India, also now wants to try growing Indian varieties in America, although, this is not the first such attempt.

In the 1880s, mango seeds and saplings from alphonso and mulgoa were planted in Florida, which failed to yield desirable results and were abandoned, according to Plant-O-Gram Nursery in Florida.

But Savani, who has acquired 45 acres of land in Captain Cook, Big Island in Hawaii, is hopeful that he will be able to grow the top 10 varieties of Indian mangoes locally. With ambitious intenttions, Savani is also negotiating another 230 acres of land in Oawo. He blames the earlier failed attempts on the wrong demography: “Florida is a sub-tropic area. The weather conditions are not suitable for mangoes that require sun and long, dry spells. Florida is humid. Mango is a sensitive fruit that cannot sustain fog and frost.”

Mexican Mangoes Dominate

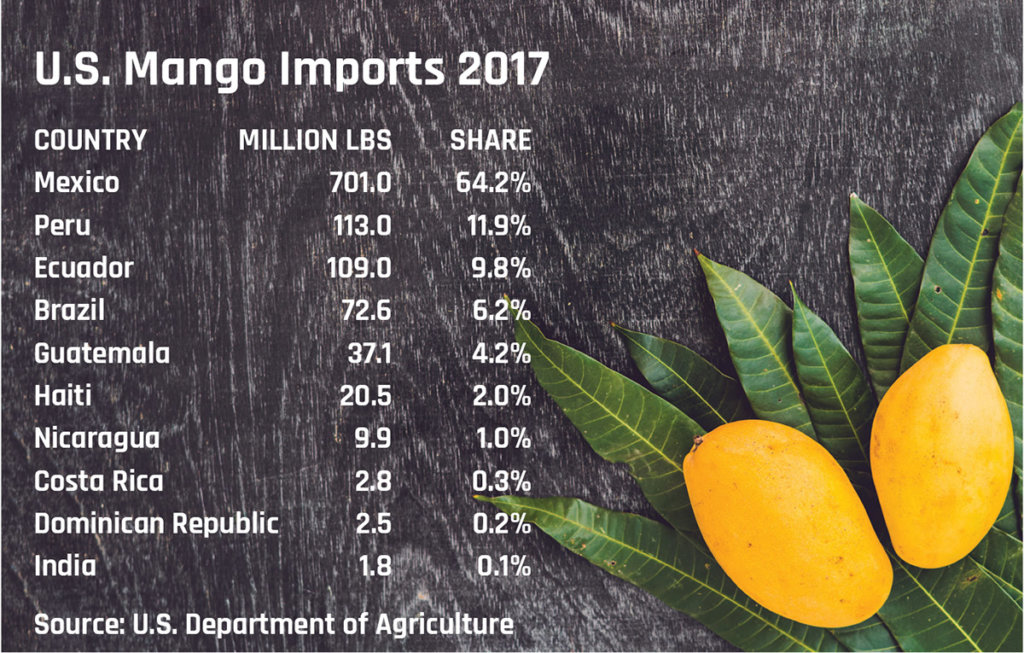

According to 2017 USDA data, Mexico accounts for 62 percent of mango imports to the United States. India accounts for just 0.6 percent — and that is even after imports of Indian mangoes more than doubled since 2015. India, the world’s largest mango grower, is also beaten out by Peru (15 percent), Ecuador (10 percent), Brazil (9 percent), Guatemala (4 percent), Haiti (3 percent) and Nicaragua (1 percent).

The value of Indian mango imports in 2017 was just $3.8 million, a fraction of the $279 million in mangoes imported from Mexico.

Savani blames the weak demand for Indian mangoes on regulations: “The problem we have is that it is illegal to bring mango scion for grafting from India so we can only get them from within the U.S. in Florida. Fortunately, they have many in the collection there. This law makes no sense to us as seeds are allowed, but they are different from the mangos. Often with mango, diseases are in the seeds and not in the wood themselves. Once our approved for quarantine greenhouse is finished early next year, we plan to petition the USDA to change this so that we may be able to bring in additional varieties.”

Phytosanitary restrictions also play a big role on the scarcity of Indian mangoes in the United States, Savani says: “Mangoes are susceptible to fruit flies and there are not enough gamma radiation facilities to cater to the USDA requirements of pesticide free fruits. Also, we currently ship the fruits in passenger airlines and space is always a constraint.”

International Mango Organization’s Cavan concurs: “The primary obstacle is the distance from the USA marketplace and phytosanitary restrictions in that order. The higher brix (sweeter) fruit have a shorter shelf life making less expensive freight routes such as ocean freight virtually impossible.”

Love adds: “There is also a problem getting the Indian government to give a phytosanitary certificate so that we can export from India. I’ve tried a number of times to bring in approved trees and different jackfruit varieties, but with no luck. Currently, from India, we can only bring in seeds to try. Last year for example we produced our first kokum.”

Cavan says that Indian cultivations should be planted in suitable zones closer to the North American market. He adds, “IMO has lobbied for the use of irradiation as a phytosanitary protocol as the more popular method of hot water treatment ruins the flavor of the fruit which must be harvested immature and denies consumer access to optimum flavor.”

As the Indian American population grows, the demand for Indian mangoes is bound to escalate. Those in the trade say that India needs to do much more to introduce and popularize their mangoes in the US.

Love says: “Distribution of Indian mangoes is minimal when compared to South American and Mexican fruit. There needs to be taste tests and promotions within the large grocery stores. When visiting the mainland U.S., I’ve never seen them for sale. So, it is always hard to buy when you can’t find them. India also must compete with the Philippines (also excellent mangos), Vietnam, elsewhere in South East Asia and even Australia and Taiwan. Of course, local California mangoes are a major part of the market in California. As a new player, India must fight hard for a share of the growing market which means a much more proactive program with chefs, grocery stores and large international food markets. Even in our tiny newspaper food section we see mango recipes, but the mangoes are always from Ecuador or Peru or Mexico.”

Savani argues that mango festivals, mango pop-ups and events around Indian mangoes would eventually establish how he likes to describe the fruit — “Mangoes from rest of the world are salad fruits, while Indian mangoes are gourmet.”

1 Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment Login