Magazine

Reverse Take

We return to the villages in India visited by US. presidents after the camera lights have turned off and the make-up washed away.

| Like three of the five previous U.S. presidents to visit India before him, Pres. Barack Obama took the customary pilgrimage to an Indian village. Unlike his predecessors, however, he did not actually set foot in one. Instead, in a tip of the hat to India’s vaunted high tech sector, he visited with the residents of Kanpura — a non-descript village, 40 kms. from Ajmer in Rajasthan — via a video link from Mumbai.

The video conference purportedly allowed Obama to observe firsthand the IT revolution powering grassroots democracy in rural India at the gram panchayat level, the smallest unit of democratically elected bodies in India. Obama was suitably impressed by “this terrific experiment in democracy,” raving: “One of the incredible benefits of the technology we’re seeing right here is that in many ways India may be in a position to leapfrog some of the intermediate stages of government service delivery, avoiding some of the 20th century mechanisms for delivering services and going straight to the 21st.” Unbeknownst to Obama, the real efficiency of the hi tech experiment — possibly the most important one for Indian officials — lay in the fact that it prevented real life village conditions from intruding upon the shining and spectacular, ready-for-business India on display for the world’s preeminent visitor and his accompanying international media entourage. Far from the range of prying foreign cameras, the marvelous technological efficiency of the

videoconference masked the lack of the very transparency and accountability that the U.S. president was at that moment extolling. For this investigation, Little India reporters fanned out to the villages blessed with U.S. presidential visits during the past half century to report on what happens after the camera lights have been turned off and the cosmetics and make-up washed away. Barack Obama Kanpura, Rajasthan November 2010 In contrast with previous U.S. presidential visits, the India that greeted Obama had

transformed from a developing country begging for American largesse to an economic juggernaut, one the U.S. was courting as a business partner, for in Obama’s rousing words to parliament “India is not simply emerging; India has already emerged.” The painful realities of 700 million rural Indians, half of whom subsist on under $1 a day in the nation’s 650,000 villages, did not quite square with the economic power theater Indian officials wanted to project. What better to discourage embarrassing images from being beamed by village trotting journalists from the global media than to plan the presidential visit via video satellite, showcasing India’s IT prowess to boot. Almost no journalist actually visited the village that heard Obama’s “Namaste.” Enroute to Kanpura, this reporter encountered scores of stray cattle grazing around people sleeping along the road. Fortunately, neither human nor animal ran any risk of being run over as the unpaved roads are so dangerously unkempt that few automobiles would dare venture on them. Perhaps that is one of the “leapfrogging” advantages of the internet — bypassing 20th century infrastructure development along the path to the 21st century. Stationary webcams don’t move along the lanes of the village and a single frame can make even the grubbiest place look spectacular. Shiv Shankar Singh, the gram sewak at the panchayat office in Kanpura, is the happiest man in the village with the optical-fiber-connectivity: “My task of coordinating various administrative certificates, registrations and enrollments for the villagers has become easier and faster.” Shankar may be happy with the broadband, but an aide, Satya Narain Chippa, scoffs: “The groundwater in and around the place is hard and undrinkable. Supply lines, that bring drinkable water, are opened for not more than an hour once every few days. And each tap of such lines is shared by scores of families. Power supply needed to pump ground water too

remains scant and comes only for a few hours in a day.” The latest IT infrastructure, including the broadband internet connectivity showcased to Pres. Obama, is of dubious value to villagers. Veer Singh Kachawaha, the principal of the Government Secondary School in Kanpura, says: “I don’t know a single person in this village who knows how to operate a computer. I am not sure how the people around would get to use internet. Moreover, electricity is so scarce how would the system run?” Manak Chand, a senior teacher at the school, waves to a computer that is no better than scrap:

“This was provided to us 10 years ago. Since long it is lying unused. The scheme terminated and the contractual instructor stopped coming. Since then we are trying to preserve it in the best possible manner.” That is the added burden for Shiv Raj, the headmaster at Kanpura’s primary school, which received three new machines in the wake of Obama’s visit. The glittering systems stand packed and untouched in his office. “But then I have a different set of problems. Already facing a crunch of teachers, who would teach the kids and how?” says Raj. The building and premises of his school are so barren that one wonders how it could impart even basic education to children, much less computer training. Open drains overflow around the school and in a sort of warm up before class kids vault over open sewers. One student quips, “If you can’t jump and cross the drain, you wouldn’t get admission here.” Raj has already ordered a trunk for safekeeping the computers as he juggles costs to reinforce the school’s falling gates, “That’s all I could do with the meager budget in my hands.”

Raj, of course, had no opportunity to explain his real dilemma to Pres. Obama. Instead, it was left to Sam Pitroda, Advisor to the Prime Minister on Public Information Infrastructure and Innovations, who prattled on about a million kilometers of fiber optic cable that connect 250,000 local governments in 650,000 villages via broadband for education, accountability and open government. After taking in the brief videoconference performance, Obama raved about just how impressed he was with Kanpura: “I want to congratulate all of you for doing the terrific work. And I look forward to watching this terrific experiment in democracy continue to expand all throughout India, and you’ll be a model for countries around the world.” Bill Clinton

Naila, Rajasthan March 2000 Bill Clinton became the fourth U.S. president to visit India in March 2000 and his five-day India trip was the longest by a U.S. president. His successor Pres. George W Bush’s two-day visit in March 2006 was all business, charged with the drama surrounding a nuclear deal and he did not visit a village. But Clinton’s itinerary included Naila, a small village on the outskirts of Jaipur. Pres. Clinton walked around and matched steps with Rajasthani women in Naila.

The one-hour drive to the village from Jaipur is promising. The connecting roads are relatively decent and the village looks clean. Swamps and marshes festering with garbage are noticeably absent. But that is only because there’s an acute scarcity of water in the village. Running water is available for less than an hour daily and groundwater levels are too low to tap easily. In addition, the power supply required to run water pumps is available for just a couple of hours a day. Ten years ago Naila was introduced to the global stage during Pres. Clinton’s visit. The highlight was a rural women-run dairy cooperative, where he chatted up the women and was gifted a membership card. The cooperative does not exist in the village and the building is now used as a rural health training center. There is nary a trace of the much-ballyhooed cooperative showcased to Pres. Clinton. The walls of the rooms in Fatehgarh Naila building, constructed in 1875, still don beautiful and intricate golden paintings. The courtyard in the center of the mesmerizing structure offered a floor for Clinton to dance to Rajasthani

tunes. Kishan Lal, elder brother of the present sarpanch of Naila, says: “Most of the women who danced around Clinton didn’t even belong to the village. They were simply roped in from neighboring villages for the show. No dairy co-operative was ever run in the village. It was all staged for the day.” Mohini Bai, whose claim to fame is that she tied a rakhi around the wrist of the world’s most powerful man, recalls: “I run a women society in the village and was offered a chance to showcase the concept before Clinton. We hoped that with the event, our work will be highlighted and the villagers would get some support from the government or any organization. A ball-point-pen with American government stamp on it is all that I got. Haven’t used it yet. I don’t know it will write or not.” At the time though, Naila was smitten with Clinton and there is even a girl named after the former president’s daughter Chelsea in the village. Inspired by the presidential visit, a local zari craftsman renamed his daughter Chaitanya Kumari, who was born just a few days prior

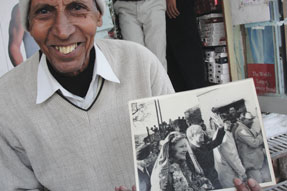

to Clinton’s visit, as Chelsea Chaturvedi. Ironically her elder sister is named Monica, as in Monica Lewinsky, the infamous intern with whom Clinton admitted to having an “improper relationship.” The shy girls are local celebrities as every media person visiting Naila desires to interview them. But the world famous Chelsea and Monica of Naila do not have a school, beyond secondary, to attend in Naila. Shankar Gupta, the village’s gram sewak, shares his fond memories of Clinton’s visit and has carefully preserved photographs and newspaper clipping of the day’s coverage. He regrets the fact that the girls’ school in Naila still awaits upgrading, which was promised when the president visited the village. “Most benefited of Clinton’s visit after my mother who got a pen, was this Rajkiya Balika Madhyamik Vidyalaya,” says Shankar, Mohini Bai’s son. “The school rose to secondary level, got a few chairs and four computers. A decade gone by, there doesn’t seem to be any further entry in the school’s inventory. The machines too lie defunct waiting for an instructor. There

is an alarming scarcity of teachers, the building is falling, and the girls are forced to study under the open sky.” The government health center, which is run out of the haveli where Clinton shook a leg is rudimentary. Devki Nandan Sharma, a Naila resident who works as a journalist in a neighboring town, says: “The center is fine for pregnancy related counseling and the normal delivery at the max. Other than treating the basic ailments like cold-cough-fever and vaccination, the best you could expect from the center is a referral to government hospital in Jaipur, which is more than 20 kilometers from village.” Jimmy Carter Carterpuri, Haryana

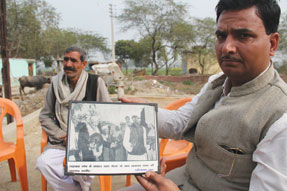

January 1978 Pres. Jimmy Carter was the third U.S. president to visit India. His predecessor Pres. Richard Nixon’s 23-hour stopover in India in 1964 did not allow time for a rural visit. Carter undertook an emotional journey to Daulatpur Nasirabad, a small village near Gurgaon in Haryana, where his mother Lillian Carter had befriended the village Lambardar (headman) during her time in India. Kartar Singh, 70, who was postmaster in the village during Carter’s visit, says: “Ours is no ordinary village. A boy from our village went on to become the president of America. Name any city of India which could boast of something like that.” Kartar, like other elderly men in the village, is convinced that Carter was born in the village. The quaint and wildly popular myth in the village is, of course, untrue. Jimmy Carter, Lillian

Carter’s eldest child, was born in Plains, Ga., on Oct 1, 1924, long before Lillian Carter visited India as a Peace Corps volunteer in 1966 at the age of 68. Indeed, had Carter been born in Daulatpur, as some villagers contend, he would have been ineligible to run for U.S. president, the very reason the villagers desire to stake a claim to him. Fortunately for Carter, there was no Tea Party around during his presidency, which would surely have dogged him over his eligibility to serve as president, much as the Birther movement has stoked controversy around Pres. Barack Obama, falsely alleging he was born in Kenya and therefore ineligible to run for president. Pres. Carter and First Lady Rosalynn Carter visited the home where Lillian Carter had stayed and presented the village with its first television set. His eyes glittering with the fond memories of the past, Singh said, “When Carter was leaving, he asked Morarji Desai, the then prime minister, if he could do anything for the village. Desai declined the offer saying that India would take care of it.” Daulatpur was re-christened as Carterpuri, permanently

imprinting Carter’s legacy, but the village remains neglected, although creeping urbanization around Gurgaon might yet touch it in the coming decades. For now though, the roads remain unpaved and the village lacks basic amenities. Kartar Singh recalls wistfully: “In my 70 years of life in Carterpuri, of which I spent 40 years serving as the postmaster of the village, I don’t remember any other day when the village has been groomed so diligently. The roads were all brushed and sprinkled, the administration generously whitewashed all around and it was the first and the last day we saw all those vehicles, workers and machinery.” With a wide grin, he adds, “They didn’t spare even the cow-dung-cakes used for fuel from painting white, seems as if they wanted to paint a ‘White House’ picture of the village for Jimmy.” His brother Awrar Singh adds: “For the villagers, it was the homecoming of an old local. We didn’t expect anything from him, all that we wanted then and now is that the government

builds some educational institute or hospital in Carter’s name, the place will find a better relevance for the generations to come.” The villagers remain emotionally attached to Carter. They celebrate the day he won the Nobel Prize. And they organize a gathering on the annual village holiday every Jan. 3, the day Jimmy Carter came calling. However, one village shopkeeper rues Carter’s visit: “We gained nothing and lost our identity too. What good is it to lose an age-old name? We were better off with the former. As it is, nothing else changed with Carter’s visit.” Three decades after Carter’s visit, the village has yet to see the hospital that was promised to villagers. Awtar’s son points to the vacant plot with a dilapidated boundary adorning the sign board of a “Health Dispensary,” painfully remarking, “This is how India has taken care of us.”

The village, population 5,000 has just one primary and one secondary school. For higher education, students have to travel to adjacent towns. Says Rama Devi, an elderly woman in the village: “For boys it’s still fine, what to do for the girls? You can’t expect villagers to send their young daughters so far for studies. As it is, the urbanization around has worsened the law-and-order situation. It is not safe at all. The cabbies and migrant workers flocking around find us soft target.” Abutting the village, the hi-tech city of Gurgaon boasts some of the best infrastructural amenities in the country. Gurgaon has developed as one of the prime hubs of outsourcing in India. Complains Kailash, a young shopkeeper in the village: “We get a limited electric supply each day and have to bear with it. All around our village, Gurgaon enjoys uncut power supply 24 x 7. Is the discrimination only because we work for our own citizens and they answer the calls from foreign countries?” Dwight D. Eisenhower Laramada, Uttar Pradesh December 1959

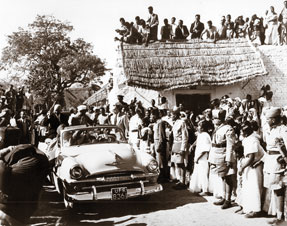

Pres. Dwight D Eisenhower was the first U.S. president to visit India in December 1959. He was proudly escorted to Laramada village, near Agra, by Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. The village now lies deserted, discarded and all too forgotten. Hardly anyone has heard of Laramada and it was difficult to find anyone who knew of the village even 3 miles away from it. Roshan Lal, a village senior, recalls the presidential visit vividly: “Tractors had started coming in months prior to his visit. Loads of beautification was done all around. Roads, lanes, fountains, etc. were built all over. We got the electricity just a few days before his arrival.” Barfi Devi, who was a young woman when the U.S. president and Indian prime minister visited the village, served them a meal. Now almost deaf, she could not understand most of this reporter’s questions, but perked up on hearing the name of Jawaharlal Nehru: “He asked me to remove the ghunghat and show my face. Eisenhower said that I was like his daughter and he wouldn’t ever get a chance to see me ever again. I did show them my face and they clicked my photos too. He was very happy to see me.” Her grandson Mahavir Singh pointed to the stage at the chaupal where the two leaders addressed the villagers and promised them a bright future. Now only overflowing drains and a crumbling panchayatmark the stage. Villagers say that Eisenhower had adopted the village that day and promised to convert it into an education center. Nothing materialized, except a letter addressed to Mahavir Singh’s grandfather, Karan Singh. Laramada, population 4,500, lacks a senior secondary school even today. Thanks to the initiative of V.S. Tomar, 50 years after the U.S. president’s visit, Laramada has a degree college. Tomar, who was a 21-year-old student at the time of Eisenhower’s visit, set up the college with his son Alok Tomar. Says V.S. Tomar: “I went to see the U.S. president and Nehruji all the way to Laramada. The promises and the village looked great that day. However, nothing followed since. My son took it upon himself to make it happen. What Eisenhower and Nehru promised was delivered only by my son.” Alok Tomar dreams of medical facilities for the village and has been plugging the project for years. Has he sought government support? Tomar scoffs: “We built the college eight years ago. To this day, the government has not been able to provide us with an electricity connection, though the building is just a few meters away from the last pole. What could you expect for from the government?” (Achal Mehra contributed to this report.) Photos: Jeet Alexander.

|

You must be logged in to post a comment Login