Life

Retirement: An Iconic Struggle

I watched with young and startled eyes as my grandfather stormed into my house, gave my quiet father a mouthful and stormed away. It was the first time I witnessed a big deal being made about retirement.

|

I watched with young and startled eyes as my grandfather stormed into my house, gave my quiet father a mouthful and stormed away. It was the first time I witnessed a big deal being made about retirement. My grandfather was upset that his obedient son had, against his wishes, decided to take voluntary retirement from his company to focus full time on teaching. Although my father didn’t fall into the category, I figure smart companies try to get rid of dead wood by tempting older, self-serving and often mulish liabilities to leave the ship. The employee does not usually complain, because the severance package is designed to offset the risk inherent in taking a new job. Today, I am convinced that the virtue of retirement lies in its timing. You know you got it right when most people around you openly wish you stayed. Looking at several icons around me, I have noticed with regret that the right timing, unfortunately, often loses the battle to an aversion to relinquish.

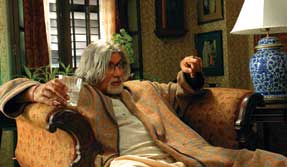

Take Lata Mangeshkar: the sweetness of her voice sets off a wave of goose bumps as she sings for Nargis, “Aaja sanam madhur chandni mein hum,” in Chori Chori, a 1956-remake of It Happened One Night. Its mellifluousness and effortless charm that makes me cringe when I listen to Lata in movies like Dil To Pagal Hai. “I love this song,” remarked a friend, referring to a number from the 2004 mega-hit Veer Zaara, “till the part when Lata joins in.” Many of her fans may not agree, but in my assessment she should have quit in the early to mid-1980s when Bollywood music was afflicted with insipid and pedestrian scores. Amitabh Bachchan is another icon who has outlived his career. I had to turn off the DVD even before the film took off, because I couldn’t bring myself to witness the degeneration of the stylish and nifty Vijay of the 1970s as his hoary eyes lusted for an 18-year old squirt in Nishabd. Some of his fans argue that he is doing roles now that he couldn’t have essayed during his peak. But I, for one, don’t feel the urge to rush to his movies, first day first show, as I did in his heydays. True, there are rare gems like Cheeni Kum, but they lie so deeply buried in an avalanche of lamentable fare that with every passing movie, my adoration turns into sympathy for the man who refuses to withdraw from the glare. Then there is Sachin Tendulkar. I have skipped classes to watch him bat, and have converted idle conversations into raging debates on his contribution to Indian cricket. But that was then. Today, Sachin might still be looking for that one last glory knock (which, I hope, for his sake, came at long last in his match-winning inning during the Chennai Test against England), but in the process he is trampling upon his carefully crafted image as a cricket terror every time he walks on to the field. Every time he loses his timber tamely, shabbily nicks one to the keeper, or crumples to the ground after a single, holding his calf in pain, the image blurs a little more. These days, he is falling apart physically as rapidly as an American car that has clocked 100,000 miles. During most of the calendar year, he is injured, resting, or in Australia for treatment. The agony of his fast-depleting fan base, he should understand, is a sobering blow to the very game he pledges he loves. Even the great Kapil Dev protracted his presence in Indian cricket just to become the world’s highest wicket-taker. It was saddening to see Kumble bowl wide outside the stumps to tail-enders so that Kapil could get his wickets from the other end. The Hindu lamented that Kapil’s last years “reminded one of a weary veteran past his prime and not of the enthusiastic Haryanvi who came in like a breath of fresh air.” His drawn out denouement hurt Indian cricket by delaying the grooming of bowlers like Javagal Srinath.

The famous Indian columnist, MV Kamath, while defending the dragged out Bachchan’s career, attacked cricketers like Sachin for their unwillingness to retire, noting that “Cricket is not Bollywood.” Despite some forgettable films, Kamath said, Bachchan has turned out to be bigger than the films heacted in. “The success or failure (of Bollywood stars) on the silver screen or in television channels is strictly their business,” he commented. “(But) if the Indian team performs poorly it hurts the average psyche.” Kamath is giving short shrift to the pain that millions of Bollywood enthusiasts like me must endure by witnessing the harrowing decline of their idols. This iconic struggle with retirement is a worldwide phenomenon and is not restricted to sports or glamour. Robert Mugabe, a once popular leader, has violently overstayed his welcome as Zimbabwe president, to the world’s chagrin. Then there are bewildering stories of stars coming back from retirement. Brett Favre, a Green Bay Packers quarterback whose name is mentioned in the same breath as other American Football legends, turned misty eyed as a somber nation watched him bid goodbye to the game. He reversed his decision as dramatically, following up with even more unfortunate choices, and now plays for the New York Jets. Michael Jordan, a basketball genius, came back twice from retirement; while the first created some melodramatic moments, the second soiled his legacy.

So, what prompts these heroes to corrupt their illustrious careers with feeble epilogues? Or overstay their vocation to the point of mustiness? A two-time Ironman Triathlon champion, Scott Tinley, in his book, Racing the Sunset; An Athlete’s Quest for Life After Sport, talked about how he recovered from a devastating post-retirement depression that threw his life into chaos, “You just have to let the old you die in order to let a new person grow.” Most superstars are so habituated to public adulation and attention that sudden obscurity kills their psyche. The delay in retirement is likely related to the mortification of being relegated into a nonentity, fear of having nothing to do with an occupation that defined them. Many continue to perform because they think they are still good; others because the money is good. The inability to answer the “what next” question prompts them to defer the inevitable. They don’t realize or don’t care that their selfishness has repercussions on the very people they are so dearly holding on to: an attenuating fan base, frustration among the management and colleagues, and growing despair among the new talents who await their turn. Even those who find success doing something else, experience the tug. “I’ve been successful with a lot of business things, but if I told you that took the place of boxing I’d be lying,” said George Foreman, the oldest boxer to become heavyweight champion. “The thrill of a crowd roaring for you after just winning a boxing match, nothing touches that.” Sachin Tendulkar probably gets the same thrill from watching his bat arch gracefully and the ball fly through the covers. But he should spare fans like me the agony of witnessing their slow death. What these self-serving icons need is an intelligent, but painless execution of a golden handshake.

|