Arts

Ravi Shankar Unplugged

Sukanya and Ravi Shankar on their music, life and love.

|

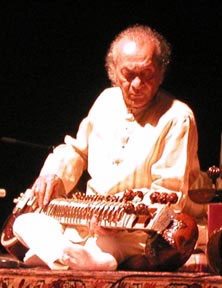

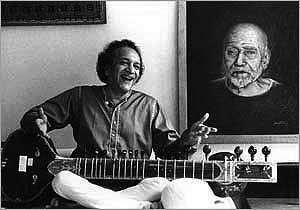

As he enters the stage, the atmosphere is electrified. The roar of the crowd and an endless standing ovation seems to move him as he clasps his hands together in acknowledgment at a recent sold out concert in Michigan. Elegantly clad, charismatic, he remains an amazing musician at 84, in spite of ill health that has dogged him in recent years. In Hindu mythology, the origin of classical music began with the first sound of the Nada Brahma or Om. The Nada Brahma was believed to be the purest sound ever made, a representation of divine power, and it is the ultimate goal of every classical musician to attain that level of purity. Ravi Shankar at 84, still creates divine music.

The first thing that strikes you about Ravi Shankar is his child like smile and beautiful deep eyes brimming with warmth and sweetness. There is humility and innate honesty with which he talks about his life. His life story has all the ingredients of a masala movie, and being a TV and movie junkie, he probably would enjoy seeing it enacted on celluloid. Uprooted at the tender age of 10 by brother Uday, Ravi Shankar moved to Paris to join his brother’s troupe of exotic dancers who had made a great name for themselves. He got a taste of glitz and glamor at a very young age and loved it, not to mention dazzling innumerable women that were spellbound by his charm and musical genius. Then he gave it all up to train for 18 hours every day, under Sarod maestro Baba Allauddin Khan. With him was Baba’s son Ali Akbar Khan, and Baba’s gifted daughter Annapurna Devi whom he married and had son Shubho. Ali Akbar Khan went on to achieve world fame in the Sarod and today operates a music school in California.

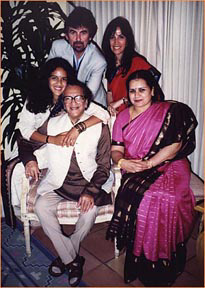

Raviji’s daughter Anoushka is a spitting image of him. Anoushka says she has to stare at her father all the time when they perform together, because they never rehearse and 90 percent of the time it is all improvised on stage. Anoushka was born to Sukanya Ranjan a Carnatic vocalist and her famous father while Sukanya was still married to another man. Ravi Shankar married Sukanya when Anoushka was 7 years old and they moved to California, where they have been living ever since though they have been spending a lot of time in India recently. The love bonds of Raviji and Sukanya are still strong after three decades, despite the 34 year age difference between the two. “They are such a beautiful couple,” says Anoushka. “It’s so cute. They still don’t know that we all know that they still hold hands under the table, and my dad will never go to sleep without saying good night to my mom and they still leave these little I love you notes for each other. It is so amazing, and after so many years!” Sukanya’s smile can light up the darkest interiors, and every time you meet the Shankars you feel like you’ve just been enveloped in a huge blanket of warmth, simplicity and genuine affection. In a candid and exclusive interview with Little India, that began after a concert in Michigan and ended in Illinois, Ravi and Sukanya Shankar talk about making music, their life together, Anoushka and Norah Jones, his two wonderfully gifted daughters, his son Shubho, and the state of classical music today. What are the earliest memories of music?

Ravi: I was lying in Benaras on the roof at night, watching the stars and hearing my mother sing thumris to me as she put me to sleep. My father was highly educated and in the service of the Maharaja of Jhalwar, a small native state in Rajasthan. But he was never there while I was growing up. My mother had become a close friend or sakhi of the queen, among the ladies in the queen’s court. She was not a trained musician, but she heard many famous lady musicians like Gohar Jan, Zohra jan and others who visited the zenana (ladies court). She had a very sweet melodious voice and sang a variety of folk songs, thumri, kajra and dadra, apart from telling me mythological stories and the names of all the stars and about her childhood. I was very close to her and she was a strong, but short, influence in my life. I was barely 12 when we parted and 16 when she died. Sukanya: I come from a family of musicians and music lovers from both sides. My father didn’t like us singing outside, but loved music and I saw all these musicians coming home. I was a child prodigy at four but hated music, because as soon as I would come from school the music teacher would always be sitting there waiting for me. My father however loved to hear me sing so I had to continue my training whether I liked it or not. I first saw Raviji perform live at the music academy in Madras when I was about 10 or 11. It was a mesmerizing experience. It was so electrifying and fantastic it seemed like Maya, an illusion, not real or of this world. But after it was over, I forgot about it. It was much later when I went to London and heard Raviji’s music again that I started liking music.

I met him at 17, in the early 70s, when my friend Viji, Lakshmi Shankar’s daughter, asked me to play tanpura with Raviji at a concert. I still remember the first time I saw him. He was coming down the stairs, he was so handsome and godlike, that I was just frozen to the spot. I even forgot to do pranam, until Lakshmi aunty nudged me and asked me to do namaskaram! It took 5 more years and the rendition of raga Yaman Kalyan, I hear that did it for you! You chose to have Anoushka with Raviji even while married to your ex husband. That took a lot of courage, especially since you came from a traditional and conservative background. How did Raviji respond to your decision? Sukanya: I was so much in love with him, and maybe that is what gave me the courage. He was involved with other women too and had hrefused many times to have the baby with me. The one thing that Raviji has always had is honesty. Almost all his ex-girlfriends are friends with him to this day. He never misled anyone. He was traveling a lot and there were always women, but they knew what to expect. He is also a deeply caring person. All the women he has been with agree when I say this, he made them feel very special. At one time I was one of those women, but he made me feel as if I was the only one, the most precious thing in his life. He felt he could not participate or accept responsibility as a father or give the baby his name and he told me that upfront. He wasn’t sure he wanted to get married. He was also told it was not good for his reputation. But I was adamant. I felt that since I couldn’t have him, his baby would be a part of him, that would always be with me. But Anoushka from the time she was a child had this deep attachment for him. Once when she was little she saw him on TV and said baba looks like me doesn’t he?

She would always want to run to him and dip her biscuit in his tea and I was petrified she would do it in public. Anoushka has always been mature for her age and somehow there is this deep bond between them and you tend to gravitate to where you belong. Raviji, your brother Uday Shankar was way ahead of his times. Not only was he a wonderful painter he also took Europe by storm bringing Indian dance and music to audiences abroad. I read that James Joyce said of him, “He moves on stage like a semi-divine being. Believe me there are still some beautiful things left in this world.” Ravi: Indeed, he was the first person who taught me that our art and cultural heritage was to be revered .He was not a trained dancer and mostly self taught. He could simply visualize movements while looking at photographs and sculptures and he also had seen folk dances at different festival and came up with brilliant, original and unique work. Of course later on he did study art, dance and history of different regions of India. He was also the first person to understand the importance of presentation. In the old days the musicians were supported financially by royalty and had to perform only before royalty. When the time came to perform before the regular audience neither they nor the audience knew how to go about things. Even the legendary musicians did not know how to present themselves before the public, what and how much to talk. Unfortunately there are still those who come up on stage and start bragging about their gharana and lineage and put other musicians down. I deplored that, and made it a point to focus on the music and the elegance of presentation. Luckily the younger generation has embraced that as well and most of them let their music speak for itself. My brother was the person who taught me a lot about the right stage setting, lighting, placing incense, and all the rules of decorum, and how to present the performance with elegance. As a result I have been very strict about certain things at my concert. I always ask for a proper stage, I don’t allow smoking and drinking and unnecessary chattering. I was criticized for that and told oh you are too westernized, this is not a western concert where every one has to stay quiet. We like saying wah wah. I said its okay to wah wah at the appropriate moment, but I will not allow business talk and women discussing their ornaments and people drinking and eating peanuts during a performance. You were initiated into this world of glitz and glamour at the tender age of ten, when your mother agreed to go with your brother and other family members with your brother’s troupe to Paris. How did that affect your development and how have you managed to keep a straight head through the years of such tremendous fame and celebrity? Ravi: I think my one regret is that I grew up far too quickly. I was surrounded by celebrities and beautiful women, all through the growing years so it was a way of life and something very normal for me. All the so called celebrities be it the great classical performers or people like Marlon Brando or Peter Sellers, were very sweet to me. It was exciting being surrounded by music, dance and being pampered, but I really didn’t have a childhood as such. It was when I was a little over 12 years that I started participating in dance and music in a more involved way. My brother was forever creating all these ballets on Shiva, Krishna and we all had to read a lot. I had read Mahabharata and Ramayana while I was in Paris itself, along with the literature of Tagore and was deeply engrossed in history and culture of our country from the very beginning. You met the legendary Rabindranath Tagore. Tell me about that meeting. Ravi: I still remember it very vividly. I was around 13 or 14 and to this day I have never met anyone like him. He was the Leonardo Da Vinci of India, so multi-talented.

Looking at him was like looking at the sun. He had blazing dark eyes, and when we met, he remembered my father who had been in the committee working on Tagore’s Nobel prize nomination along with the famous poet W.B. Yeats. He put his hand on my head and said in Bengali, “babur mauto hawo, dadar mauto hawo.” It meant “be like your father, be like your brother.” I felt a shiver go through my entire being. It was an electrifying moment. You were doing very well abroad, living the good life, and yet you chucked everything up to go to a remote village of Maihar and study music under the very strict and austere guru, the legendary, unpredictable Sarod maestro Baba Allauddin Khan. I believe you saw him perform under strange circumstances and were very intrigued! Ravi:I met him in Calcutta in 1934 at one of the music festivals. I don’t think I will ever come across a personality like him in this lifetime. He had a band of orphan boys called the Maihar band. He was a genius. He had two sides to him, the sweet loving side and then the Shaivite side where if he saw a student making a mistake his temper was legendary. He was never unkind to good students, but had no patience with the dumber ones. It was amazing to see how he had taught the band so many different instruments. I believe he had even made an instrument out of steel household pipes and something that was a combination of sitar and banjo. Ravi: Indeed. He played the violin brilliantly, but strangely used his right hand for writing and playing most instrument except the violin and sarod. He was also an amazing drummer and if anyone played the tabla badly God help him. It was very strange to see that he was getting upset and beating up his musicians on stage with his bow. He was a very simple man, a sadhu. In fact I would be reminded of stories of the sage Durvasa and his temper when I saw baba. He had the same saintliness as well. He was vaishnav most of the time and a shaivate when he was teaching!

Baba Allauddin Khan, joined my brother’s troupe in 1935 and that immediately shifted my focus from dance to music, as I was more of a dancer then. I used to fiddle with all the instruments including sitar without really being serious, but baba’s genius bowled me over totally. After a year he went back to India, when I was 16. But 2 ? years later I followed him to his village of Maihar, leaving my wonderful luxurious life with my brother. I heard you had to undergo rigorous training for 18 hours and tried to run away once, when Baba yelled at you, and it was his son, the Sarod maestro Ali Akbar Khan who persuaded you to come back! What do you remember most as you look back fondly. You dedicated the first sitar concerto with the London Symphony Orchestra to his memory. Ravi: Yes that’s very true. I had been very spoilt by the glamor and glitz of the life in Paris, where everyone fawned over me. In Maihar, everything was so Spartan and Baba was so strict, although he never raised his hand on me, while he mercilessly beat his other disciples. He even tied his son Ali Akbar to a tree and beat him. That strict discipline got to me and I did try to run away. But better sense prevailed and I am glad I came back. Baba was the only guru I had and I learnt a lot from him. He loved me deeply and had promised my mother to look after me and had adopted me as his second son. He taught me that no doubt today we had to earn money from music since the royalty was no longer there to support us, but music for us is devotion, meditation and prayer and we must always preserve its sanctity. That is why I did not even spare the then Prince of Jodhpur, Hanumant Singh who was drinking with his friends at the Tajmahal Hotel. I told him I would not play until he stopped. The same thing happened with the Maharaja of Nathadwara. I saw the famous singer Heera Bai sitting on a durree, next to the maharaja, and his cronies singing as they drank. I insisted on a platform above the audience and that every one stops drinking. There were times I left without playing if I saw the atmosphere was not right. This was something I insisted on as early as returning from Maihar and starting my public career.

Baba was unlike any classical traditional musician I know. He was deeply rooted to tradition, but also so brilliantly innovative and creative. When he came to Europe, I took him to all the western classical music concerts and he listened to records as well. He experimented with so many things within the Maihar band and was far ahead of his times, but never got to showcase that brilliance on stage because he was a very nervous performer. He would get very agitated if even a little thing went wrong and lose control. He would have enjoyed the first concerto and the others I wrote subsequently. Contrary to popular belief that the Beatles introduced Ravi Shankar to the West, you undertook your first tour of Europe and United States in 1956. Ravi: It was actually Yehudi Menhuin, whom I had met in 1952 and struck a friendship with, who asked me to come over and talked a lot about my talent and Indian music. I met George Harrison almost 10 years later in 1966. I was already very well known in Europe and USA by then, playing in all the famous auditoriums. The only thing that happened was that my meeting George and the first part of the hippie movement happened simultaneously. They called themselves the flower children, there was freedom of everything, the youth revolution. It was very sweet and innocent then and it helped people become more open minded towards music of other nations. Suddenly the younger generation took to my music in a big way, and I became a super star in the pop sense. Even though the hippie movement had started, there were a lot of good things that I saw. It was at the beginning of the flower children era, with sincere messages of love and peace and spirituality. There was a lot of innocence, and I enjoyed performing at the Monterey Pop festival. However, 2 years later when I played in Woodstock I saw everything going downhill. Apart from drugs, I heard there was violence, even rape, theft and robbery. The superficiality with which these people were treating India, the clichéd scenario with the so-called Kamasutra Parties with hashish, the mockery of Buddhism really upset me. I would constantly admonish these people whenever they came to my concerts to stop taking drugs, smoking, to behave themselves. I’d tell them, “You wouldn’t be doing this if you went for a western classical music concert. Indian classical music too cannot be heard like pop and rock.” After my unpleasant experience at Woodstock, I stopped playing at all pop and rock concerts, much to the dismay of my managers who were trying to cash in on my popularity, but I’m very proud to say I stood my ground and went through that period with dignity. Now I meet some of those middle-aged people, the hippies of yesterday and thankfully, they have sobered down. Of course nowadays I only play in closed auditoriums like Royal Albert Hall, or Carnegie Hall where smoking or misbehavior is not allowed. Ravi: You are one of those very rare people who has pointed that fact out. It was like walking on a thin edged sword. On one hand I was receiving so much love and appreciation abroad, and I would have become a multimillionaire many times over and won many more Grammies, if I had jammed with all these musicians from the west. I composed the raga and talas for Menhuin and Jean Pierre Ramphal and they played my compositions. I never wanted to play Bach or Beethoven with them because I felt I was not trained in western classical music and hence it would be inappropriate for me to try a hand at it. The Indian musicians and critics, on the other hand, were very unkind misrepresenting what I was doing. They claimed I was Americanizing and commercializing our music, that I had become part of the pop and rock culture. My music, tantra, kamasutra, sex and drugs all were being lumped together. It was a strange atmosphere for almost 10 years Even the late Ustad Vilayat Khan, a wonderful musician, God bless his soul, would take digs at me. In the first 20 minutes of his recital he would say something to the effect of this is not the ” Beatley Sitar” that I’m playing this is the real sitar!

In fact I hated that loud and drug infested aspect of music. I had walked away from watching Jimi Hendrix because he was being obscene and set fire to his guitar. It was such disrespect to the instrument. Discordant music makes me physically ill. I have been a composer myself and I love to experiment all the time, but whatever I composed or experimented with was based on Indian music, be it classical or contemporary. But you will notice that I have never jammed with any jazz or rock artist. I am personally not interested in fusion music. It is very fashionable and popular today, but it will be forgotten soon. It is more of a gimmicky thing to sell records. I don’t want to criticize, but personally it’s not my thing. It was exhausting work, but I would go back to India and play the same raga for 5 hours, concert after concert, to prove to my critics that I was still as immersed in tradition and all I was trying to do was create an appreciation and understanding of our music. Today a lot of those musicians who criticized me have reaped the benefits along with their children, by finding fame and appreciation here. Since you mentioned the western artists and your collaboration with them, could you touch on those exceptional creations. Your West meets East CD with Yehudi Menhuin, the concerto for Sitar with the London Symphony Orchestra, and one of my personal favorites, The Chants of India, to name a few. Ravi: The first Concerto for Sitar was commissioned to me by the London Symphony Orchestra. Initially I thought that it would be difficult to handle sitar with the whole symphony orchestra. That is why I insisted on having amplification for the sitar. There are sections where the sitar and the orchestra perform separately, and again where they blend. It did require practice, but the end result was satisfying, as it was a unique thing to have done at that time. Of course, Indian classical music is all about improvisation. I had written the piece for sitar with enough space to improvise, especially the piece where I play coming in to lead the orchestra. The album with Yehudi Menhuin came out of a deep friendship and love that we shared. He was the director of one of the famous festivals, The Bath Festival in England at that time, and I had once mentioned to him that we should do a violin-sitar duet together. The opportunity arose in 1966. I wrote the entire composition and taught him everything. He was such a great musician, but what humility and sweetness, and he had such a deep admiration for different cultures, and so it worked out very well. Of course, I collaborated with others too, but whatever I have written has all been based on our ragas and talas. The Chants of India was something I had always wanted to do, and I want to do many such similar experiments. If you go to Chennai, you’ll find so many CDs on similar lines. They are so many people who have done chanting for years, others have tried to do it with classical music, and some have even tried to do it with pop music! So, I wanted to do it as traditionally as possible, and yet not to make it exclusively for just the Indians, because there is so much interest in the west in our Vedic culture now. I wanted to make it more international but without the influence of western instruments or orchestra. I wanted the album to be a genuine creation of Vedic mantras but with a universal appeal. This remains one of my favorites. Sukanaya: We were staying at George’s house and the recording was going on downstairs. I was not well that day and he dragged me downstairs to sing on it with him in spite of my hrefusing. Anoushka too was involved. George was really a true friend. Anoushka and Raviji and he would do a lot of fun things especially punning on words. Raviji, what are your memories of George Harrison and who would you say was the most gifted of the Beatles. Ravi: Well it is a popular perception that John Lennon was the best. I don’t think he was the best musically, but I think he was a wonderful writer. I introduced George to the philosophy of Vivekananda, and gave him the book Autobiography of a Yogi, to read. In later years George’s work took on a deeper, very philosophical meaning and musically he had become fantastic. He attributed it to my influence in his life. Whatever it was, he did develop a very deep appreciation of Indian culture and philosophy and it showed in his work and his life. The famous Jazz musician John Coltrane was also very deeply influenced by your music. He even named his son Ravi after you. When his hit album Meditations came out every one was agog, but you said that CD disturbed you. Ravi: Yes I had heard that he had been very influenced by my music and when I met him he had given up drugs, turned vegetarian and had been reading books on Indian philosophy. He met me a few times, studied with me and was fascinated by our music and the improvisation. In spite of the turn around in his life, the CD was full of pain and shrieks, a cry for help maybe and while others were going gaga over it I told him it disturbed me deeply. I didn’t hear music, I heard pain and screams. He died soon Talking of the Beatly sitar brings me to the late sitar maestro Vilayat Khan. There was always this perceived rivalry between the two of you. You were both opposites in personality. You were this elegant charmer and he was the chameleon who could be as charming and generous, but also unpredictably brash and outspoken. There was this famous incident in Delhi in 1950 where you both played, Allauddin Khan too was in the audience and then things took a turn for the unpleasant. Ravi: Vilayat Khan was a wonderfully gifted musician, and he passed away recently after a great career. The incident that you mentioned happened when we were playing at Red Fort and Ali Akbar Khan, and tabla maestro Kishan Maharaj were also on stage with us. All the famous musicians were there. I used to organize these musical events under the Jhankar Musical Circle Series and had been doing so for three-four years. That day I was also running a fever of 102 degrees. I was told we want to have all three of you Ali Akbar myself and Vilayat Khan, together on stage. I was a bit skeptical, but said fine. Vilayat Khan was very cordial and said, “dada prem se bajayenge” (we will play with love and affection) and I said fine. I also went along with whatever he wanted: let’s play raga Manj Khamaj, he said, and I said fine, and played in whatever beat he wanted, just to keep the warmth and camaraderie. Nothing really happened that was unsavory, but the musicians from Delhi started cheering as he was tuning his sitar. The next day it all started off with the musicians from Delhi claiming Vilayat Khan had overshadowed me completely, his jhala was superior, I couldn’t keep up with him etc, etc. I still didn’t dwell much on it until it came out in the newspapers in Bombay. I was very irritated then and in fact challenged Vilayat Khan openly to a rematch at a friend’s house. The legendary classical vocalist Amir Khan was there as were Ali Akbar Khan and Kishan Maharaj. Vilayat Khan immediately appeased me by saying dada let’s not get in to this. People indulge in idle talk and unless you hear me say something in person, don’t go by hearsay. I let it go. He was such a wonderful musician, but whenever he played, the first thing he would do would do would be to make digs at me! I smile about it now, but it was a bit trying. His son Shujaat Khan did say in an interview that his father had the utmost respect for you and perhaps would not have attained the heights that he did if it wasn’t for competition from you. Ravi: Yes, Vilayat Khan did say that to me also in person also. I have no ill will against him really. Ravi: Unfortunately no. Our collaboration from the 1950s to the early 60s was indeed amazing. We had learnt from the same teacher and there was a lot of affection between us, so our juglabandi or duet was very novel, because before that there were rarely any instrumental collaborations and that two between two different instruments. As time passed we grew and developed differently and grew apart somewhere down the line. Then there were personality clashes too. He is a wonderful musician, but it’s too late to bridge the gap. Tell me about your association with Satyajit Ray. Though you have given music for several of his films he wasn’t happy and said that as a writer of music for ballet and stage you were unique, but film music was something else! Ravi: I met Ray sometime in the mid forties and I consider him a friend. He was again very multi-talented and his first film Pather Panchali for which I composed music was in my eyes the most perfect film I have seen. Everything about it, editing, direction, acting, the story line was just so perfectly balanced. The reason why Ray said the above was because around the time that I started composing music for his films I was exceedingly busy and I used to quickly come in, see the film, compose the music and run. Most musicians would stay for editing, mixing and making improvements, but the fact is whatever I come up with the first time is really my best offering. It’s true for all my compositions, not just film music. You have had a long association with both Ustad Allah Rakha and his son Zakir Hussain. Tell me about them. People say Zakir reminds them of a young Ravi Shankar in terms of presentation, versatility and talent. Ravi: That is nice to know. Ustad Allah Rakha was no doubt the greatest tabla player of his time, but it was like taking a baby with me, especially the first 10 years or so, since he didn’t speak English. I had to do all his paper work and take care of all his needs. He and I were both TV junkies! What can I say of Zakir. He is his father and more. Not only has he carried the art of the Punjab gharana to greater heights, he is very familiar with other gharanas as well. He can take any thing-nakkara, dholak, bongo, jazz, African drums and come up with amazing sounds. His stage is the world and it’s a much wider, more global world today for him than it was for his father. You are one of the rare musicians who has combined both the Carnatic and Hindustani classical music to create a very rich repertoire. Ravi: Well it has been very exciting and I have also managed to introduce ragas that are of Carnatic origin to north Indian musicians. Of course the versions are based on the Hindustani style and my own interpretations. What most people don’t realize is that before the outside influences came into India, both systems of music followed the same Bharat natya shastra and we had no problems understanding and developing our music, or keeping the same tempo or counting beats on our fingers. Even the old Pakhawaj players from the south maintained the same system and we had so much in common technically. But with the advent of the emperors came the gold coins and the musical wrestling matches where the tabla player was pitted against the vocalist, and people started playing to the galleries. As a result the two styles of music became more and more distant from each other, and today it’s more of a competition, rather than appreciation for each other. I have tried hard to bridge that gap and I think I have been fairly successful in showing the unique similarities between both genres. But with the infiltration now of jazz and rock and pop, Indian classical music is facing greater neglect in India. You see the young musicians playing and speaking the same language in big cities, all that technology and loud sounds and Bollywood type music and lack of clothing. Abroad, it’s the opposite. Sukanya: I think Raviji has grown so tremendously as a musician. His music was always amazing. He has so much more to offer today. His music is so colorful and multidimensional. It is because his life has been so multidimensional if you see his journey. Uprooted from Benaras to Paris to all over the world, the emotional ups and downs, the pain in his life, it has all enhanced and enriched his work tremendously. The only thing I find irritating is that all the new South Indian musicians have adopted the ragas from Carnatic music that he introduced, and play them in his style and not in Carnatic style. Only the old music stalwarts understand the difference. I wish they wouldn’t do that and keep his style and the old style separate. It takes away the uniqueness from both. You both have started the Ravi Shankar Center for the Arts in Delhi to combat the neglect that classical music is facing. It has been a grand but exhausting project from what I hear. Sukanya: When I married him I realized how non-materialistic he is. His awards were lying all over the place and with friends, and I’m sure there are still some lying around somewhere. That is why I laugh when people crib about him getting this or that award. It means so little to him. He is so careless. A lot of his compositions are lost because he keeps writing them on scraps of paper and forgets about them. I really believe that ours is a living tradition and we must do everything to preserve it. No matter where we live India is always home and there is no place like home. People have been very helpful, but I think the left hand doesn’t know what the right hand is doing, so one eventually ends up doing everything oneself and it’s a lot of work. Finally the building is complete and functioning. I just hope that while the young musicians are dabbling in other things they still stay close to their roots. Ravi:I have poured in a huge chunk of my own money in it. The government and other organizations have helped, but it’s not like Russia used to be where they funded everything, but then of course they controlled everything too. The center is not going to be a school. There are plenty of music schools being run by others as it is. My focus is to have seminars, invite intellectuals and like-minded people who are keen to preserve our music, to have discussions and also offer higher studies in music. It has also been gratifying to have schoolchildren visit the center and be acquainted with their cultural heritage, and hopefully get interested in music. But we have just started after the building was finally ready and more things will be added on. There is also some talk of composing for a big production in 2006. Let’s see how that works out. Let’s talk about Anoushka, Norah and your late son Shubho. There are so many distractions these days for children of celebrities. In fact your disciple and friend Harihar Rao had mentioned that your son Shubho was multitalented just like Anoushka. He could play the sarod, the surbahar and the sitar and was also an awesome painter, but he was pulled in too many different directions and by the time he did start getting it all together, he passed away tragically at a young age. Do you worry about Anoushka being pulled the same way? Ravi: Shubho was not as strong minded as Anoushka is. Shubho was a very gifted painter indeed, but he also had such a wonderful touch on the sitar and was an amazingly talented composer. He performed on all my tours in the USA, but it was the wonderful music he gave for dancer Viji Parkash’s Indian stage productions that stand out in my mind. He was very creative and had a fantastic voice. If you listen to the cd Tana Mana he has sung a short piece in Khamaj, with Lakshmi Shankar and you can hear the rich timbre of his voice. As far as Anoushka is concerned, she is very strong minded and has her mother to ground her. She so multi-talented it’s amazing. I’m not saying this because she is my daughter. She picks up things so quickly, but more than that has the ability to go into it deeply. Whether its writing, or western music or Indian classical, or acting, she is exceptional in everything from the sublime to the ridiculous. Seeing her develop from the age of 9 ? to what she is today is a great joy for me. Of course, the times have changed. I learnt music the old traditional way. It was easy to be involved, learning from a strict guru, as I had, in a small village where there were no distractions, no entertainment. As my childhood was spent in Europe and America, that strict discipline was quite tough for me. Anoushka, on the other hand, has never had to face such difficulties. Everything has been served to her on a platter. There is a 61 years difference between her and me. The world has changed so fast, the whole lifestyle of the young people of today is so different. You cannot expect them to live the strict, disciplined lifestyle of the ancient gurukul system. It is sad, but having said that I think we have to capture the essence, which is the basis of the music, and pass it on properly. By God’s grace I have done it and it has worked. The good thing is today the younger generation is so sharp that there is no need to learn for 18 hours as I used to do. All they need is planned training, but no matter how talented you are, you have to remain focused. That is why I have told Anoushka to take a year off and decide what is it that she really wants to do and then focus on it. She is getting offers for so many different things. She is working on an album which I would describe as one based on Indian classical music and some “mirch masala.” Norah is so lucky and her stars are so powerful, I’m glad she is focused on what she is so good at, and that is the way I would like to see her continue. Sukanya: Anoushka is very sharp, and she was always very advanced for her age. Raviji and she are very similar in temperament. If they have to explain something more than once they both get frustrated. She will be very professional on stage even if something is bothering her, then come backstage and kick everything out of the way. I have taught myself and her to be honest. I used to lie a lot as a kid, because I was so afraid of my father: did you do this? No I did not, was my ongoing reply. When I left for England, I said, I am not afraid of anything and I am never going to lie. Fear makes you do so many things that are dishonest. Anoushka is also a die hard romantic like Raviji and very sentimental. To this day, and she has seen Mahabharata so many times, she cries every time Karna dies! I will shake my head and say you know the story, why are you crying again, but she will. Geetu (Norah Jones’s Indian name is Geetali) is very talented also and the girls are close. One time Raviji, Geetu and Anoushka were sitting together and it was so strange to see their shoulders are shaped exactly the same. In Kerala people saw us and said oh the older daughter (Norah) looks like the mom and the younger one looks like the father. We didn’t correct them! Anoushka’s new album has a lot of techno effects. She doesn’t play much of it for us, but whatever I have heard sounds really good. I believe it’s your dream, Raviji, to compose something for Norah and Anoushka where they could play together, though Anoushka joked that they tried something but it sounded so silly they started laughing and gave up. Ravi: Well there is no pressure. I would like to create a composition, if it happens it happens, if it doesn’t work out that is okay too. In my entire life I have never come up with anything with either commercial success in mind or just to make it click. Is it true that the your greatest inspirations and musical creations are not born in a serene room with burning incense but in the toilet! Ravi (amidst laughter):Well the answer is yes. It’s very peaceful and you have your own space! If you were to relive your life again would you change anything? Ravi: I would want to be born again as an Indian musician, but I would be far less lazy, start at a younger age and work harder to better myself. Is there anything we don’t know about Ravi Shankar? Sukanya: That he is traveling with his cat who has his own suitcase full of toys! Can you believe this? We are staying in downgraded hotels and are doing a bus tour because he will not travel without his cat! He also cannot let me out of his sight. One time he was teaching and usually it is for two hours. I went to Home Depot to pick up some things for the house and returned two and a half hours later to find that he had panicked, the police had been summoned and my car was being flashed all over the place! He also has to work constantly. People say why he is working so hard. Why don’t you stop him? If I do he will fall sick! He gives also gives a hundred percent in every relationship, but there are very few people who we know to be genuinely his friends. Others show up when they need something. He is one of the kindest, most caring, totally romantic people I know. I tell him he should be giving workshops on love and romance instead of music! |