Arts

Meet the New Celebrity: Indian Art

Young collectors, big bucks and emerging diasporic artists.

|

The line of people, mostly in their 20’s and 30’s, stretched around the block. Was it an appearance by a rock star? Was it free giveaways? A new blockbuster movie or perhaps Brad Pitt in the flesh?

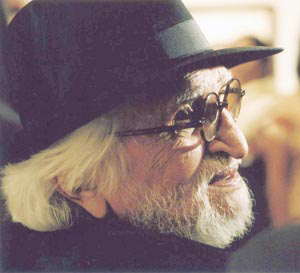

No, it was the opening of Astha Nayak, an exhibition of contemporary Indian art at Gallery Artsindia, and the place was so packed that fire safety codes prohibited any more people from entering unless some came out. But it seemed no one wanted to leave – after all, they were all waiting to catch a glimpse of the Rock Star of Contemporary Indian Art, M.F. Husain. The white maned icon finally arrived and he was mobbed for autographs and photo ops. An unbelievably youthful 90, he looked dapper in top hat and jacket with his trademark paintbrush walking stick. These days he seems to be everywhere, drawing crowds in his visits to Columbia University, Christies and the Tamarind Gallery, where he painted a 45-foot canvas live before an invited audience. Just last year, Husain agreed to paint a hundred paintings for Rs 1 billion ($21.5 million) for an Indian businessman – the biggest art deal ever in India. Both Sotheby’s and Christie’s added a contemporary Indian art portion to their Asian art March auctions last year and Sotheby’s will be including Indian artists in its July auction featuring contemporary Asian art.

At the recent Christie’s auction, Akbar Padamsee’s Mirror Image went for $186,000 while M.F. Husain’s Shatranj ke Khilari fetched $144,000 at a Sotheby’s sale. According to Hugo Weihe, head of the Indian and Southeast Asian Art at Christie’s, “The modern and contemporary section totaled $3.7 million for 94 lots, the highest total ever and was 95% sold. New world auction records were established for Padamsee, Mazumdar, Ramachandran, Bhattacharjee, Barwe and Dodiya.”

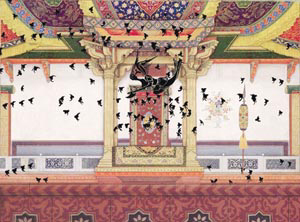

Yes, there’s certainly a buzz about Indian art. A new book titled A Guide to 101 Modern & Contemporary Indian Artists by Amrita Jhaveri was introduced at Christies; large crowds have been visiting the first ever exhibition dedicated solely to Indian contemporary art, Edge of Desire, spread over two museums at the Asia Society and the Queens Museum of Art, which is also showcasing Fatal Love, by Diaspora artists. Mainstream media from The Wall Street Journal to New York Times have carried glowing reviews of these art shows. Participating artists in Edge of Desire include a mixed bag of artists working in many different mediums, such as Sudhir Patwardhan, Atul Dodiya, Nalini Malani, Gulammohammed Sheikh, Nilima Sheikh and Vivan Sundaram. The show includes 80 cutting-edge works of sculpture, painting, drawing, installation, video and interactive media dating from 1993 to the present. “The artworks in Edge of Desire challenge preconceptions of contemporary India, whose presence in Western culture is often limited to Bollywood, yoga and outsourcing,” says Melissa Chiu, Asia Society Museum director

She points out that interest in Asian contemporary art has grown enormously over the last 10 years and there’s a greater acceptance of the fact that “art production of note can happen outside of the major art centers, such as New York and artists such as Nalini Malani and a growing number of artists who have gained international reputations.” Indeed, art is speaking in many tongues and many media, from installation art to digital art. Nalini Malani’s installation and video art are as powerful as any traditional painting could be. While Edge of Desire is about the voice of modern India, Fatal Love, the accompanying exhibition at the Queens Museum of Art is about the voice of the Diaspora and showcases the work of artists living in the United States. Tom Finkelpearl, executive director of the Queens Museum of Art, says. “This exhibition is a step in not only introducing South Asian visual art to the international art scene, but in urging New Yorkers to look closely at emerging communities here and now.”

It had been a week full of Indian art in many different locations and standing amongst the swirling crowds at Gallery Artsindia, one felt something was definitely in the air. So many of the art-lovers were new faces, young people who may not have grown up in India. Projjal Dutta, co-owner of the gallery, explained: “I don’t think this could have happened even three years back. The Indian art world has gone from strength to strength in the last five years and every year has in a way been a marker. There’s been a new high in terms of interest, in terms of appreciation, in term of prices, whatever measure you want to use. I also see a lot of younger people coming in as first time buyers. They don’t buy $100,000 works. They buy younger artists, but there’s a real surge.” M.F. Husain also has his own opinion about art’s sudden celebrity status and the role of the eight pioneers of Indian art represented in the Ashta Nayak exhibition, which include besides him, F.N.Souza, S.H.Raza, Ram Kumar, Tyeb Mehta, Akbar Padamse, V.S. Gaitonde, and J.Swaminathan. He says: “We have dedicated our lives and for the last 50 years we have been working hard, and out of those 50 years for 20 years nobody knew us. But we never left the field – now people have recognized us.”

He too has seen the new audiences, the young people reclaiming their heritage: “The younger generation is so dynamic, they have much more perception, much more feeling for what is being done in our country. In my case, it’s the younger generation that’s very close to me, rather than all the old fogies!”

What is intriguing is that the definition of Indian art may be changing, for what is Indian art? Art that is confined within the borders of India? Art created by an Indian artist in Paris, like Raza? Or by Sohan Qadri, who has lived in India and France, and now lives in Toronto and Copenhagen? Then there’s Anil Revri, who had a major show at the Corcoran Gallery of Art and lives in Washington, but whose roots are in India. Sundaram Tagore, art specialist and owner of a gallery that bears his name, says Indian art is not monolithic, nor is there one kind of Indian-ness. He points out that in today’s global village, Indians are exposed to cross-cultural ideas and the work they produce is influenced by many sources. “To be Indian, there’s no demarcatable identity,” he says. “Your Indianness comes from the genius of possessing a membrane that absorbs – and selectively absorbs – from many cultures and indigenizes it in the process. If you’re able to do that authentically and create an original voice, that means you’re able to extend our vision of the world, then you’re Indian.”

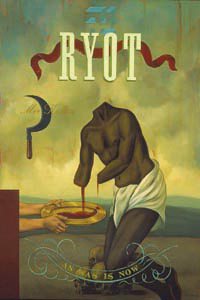

As Jaishri Abichandani, co-curator of Fatal Love points out: “It’s a hreflection of the local dialogue and impact of South Asian cultural production that runs parallel to the movement of Indian artists through the world. Shahzia Sikander, Prema Murthy and Rina Banerjee have already made major contributions to the formation of a radical new international American aesthetic.” “The concerns of the diasporic artists differ vastly from their Indian counterparts not simply in their hreflections on identity. Most of these artists take a multiple complex identity as their starting point,” she says. “Whilst some of the artists do still use their identity as a starting point, most of them have gone beyond this point to engage in much more complex questioning of what that identity means.” Over at the Talwar Gallery, the exhibition is (Desi)re, a group show of cutting edge artists of Indian origin who live in India and abroad: A. Balasubramaniam, Zarina Bhimji, Allan deSouza, Subba Ghosh, Sheila Makhijani, Ranjani Shettar, Anjum Singh and Alia Syed. They use varied media and hrefuse to site themselves or their work, transcending easy categorizations.

Says Deepak Talwar, “My artists may be of Indian origin – that may be the common thread – but when you step into the gallery, it’s the art that counts. Just the passport of the artist is irrelevant, the nationality is only how it filters through the work and it doesn’t have to look Indian to be Indian.” A telling example of this global criss-crossing can be seen in the Edge of Desire exhibit, in Made in England – a temple design for India, by L.N. Tallur. It was made during his postgraduate days in Leeds and this tongue-in-cheek installation work alludes to the NRI mania for temple building and the search for roots in the Diaspora. This inflatable plastic temple comes complete with Nandi, Shiva’s bull-vehicle and is designed for travel – ready to be deflated, boxed, and sent to the next location. An apt metaphor for exportable and inflatable culture in a shrinking world.

|

You must be logged in to post a comment Login