Arts

Hymnals Of Desire

Hindu culture embraced eroticism and sex as an essential ingredient and institutionalized it in the four exalted goals of Hindu life.

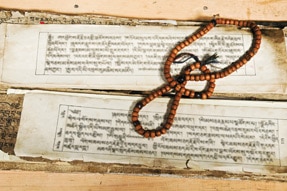

In the Book of Genesis, after creating heaven and earth, God commanded, “Let there be light.” And there was light. By contrast, according to the Rigveda, the most ancient of all Hindu scriptures: “There was no existence and there was no non-existence; there was no death and there was no deathlessness; there was no night and there was no day; there was darkness all around; in such an environment, an element self-manifested out of tapas (heat). That element was desire. (na asat asit no iti sat asit tadanim, na mrityuh asit amritam na tarhi na ratrayh ahnam asit. tamah asit tamasa guhyam agre… tapasah tat mahina ajayat yekam. Kamah tat agre samavartat adhi manasah retah prathamam yat asit (Mandala 10, Sukta 129).

Thus, whereas light was the first element in the Judeo-Christian tradition, it was desire for Hindus. On the surface, this may appear insignificant. But this difference has manifested itself in profound ways in social mores and inhibitions, as well as laws and legal prohibitions, in the countries and cultures shaped by these two different views of the genesis of the universe. While Judeo-Christian culture viewed lust and desire with suspicion and disdain, even judging it sinful (to wit the Adam, Eve and the Apple story), Hindu culture embraced eroticism and sex as an essential ingredient and institutionalized it in the four exalted goals of Hindu life — dharma (duty/righteousness), artha (wealth), kama (sensual/sexual desire) and moksha (spiritual liberation). In Hindu weddings even today, the ceremony of giving away the bride, is accompanied by this exchange between the priest and the groom: “Who is she? Who is giving her away? Whom is she being given away to?” The groom responds, “Kama, desire, is giving her to me so that I may love her. Yeah, verily, Kama is the giver and Kama is the acceptor. Please enter this ocean of Kama, with Kama, I receive you.” Since kama was elevated to the same plane as dharma, artha and moksha, it is no surprise that before the advent of Islamic and Christian rulers, Hindu culture not only tolerated erotic literature, but embraced it. Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra may be the most globally known literary work on sex and erotica out of India, but several other prominent Sanskrit poets and playwrights celebrated the sensual in works that date between the 4th to 7th century. Kalidas, widely regarded as the greatest Sanskrit poet, expounded in copious details on the beauty of Parvati and her romance with Shiva in Kumarasambhavam: “Anyonyam utpidayat utpalakshyah stana dvayam pandu tatha pravridham, madhye yatha shyam mukhasya tasya mrinal sutrantam api alabhayam (Parvati’s eyes had the beauty of a lotus flower and she had large breasts with dark nipples in the middle. Her breasts touched each other so tightly that not even a single thread of a fine fiber from the stalk of the lotus plant could be passed through between them).”

In the same book, he celebrated Parvati’s abdomen: “Madhyen sa vedi vilagna madhya valitrayam charu babhar bala, arohanartham nav yauvanen Kamasya sopanam iva prayuktam (Slender Parvati donned three muscle packs constructed by her youth so that Kamadeva, deploying the muscle packs as a ladder, could climb to the higher reaches of her body.” Parvati is no ordinary woman, she is the incarnation of goddess Kali, worshipped by a billion people today and by millions during Kalidas’ time, 1,500 to 1,600 years ago. According to oral tradition, Kalidas was struck by leprosy for his blasphemous descriptions of Parvati’s physical attributes, regaining his fingers only after writing Raghuvansham. It seems to not have deterred him as he continued his erotic writings, most famously his preeminent work Meghadutam in which he describes Yaksha’s wife, “Shroni bharat alas gamana, stokanamra stanabhyam (She walks lazily due to her large buttocks and she leans forward slightly and bends down a little due to the weight of her large breasts).” In Vikramorvashiyam, he extols Urvashi’s buttocks as well: “Pashchat nata guru nitambataya tatah asya, drishyate charu pada panktih alaktak anka (Maybe, due to her heavy buttocks, she may be heavily leaning towards the ground and she may have left prints of her feet, which were decorated red with the alaktak paste, on the wet soil).” This is the same Urvashi whose love story with the King Pururava was briefly described in the Rigveda, among the most sacred Hindu texts, in which she reminds the king of their good old days, when she was with him before their separation: “Trih sma ma ahnah shrathayah vaitasen ut sma me avyayai prinasi (We used to make love three times a day, there was no other woman I had to compete with either).” Another eminent Sanskrit poet, Harsha, wrote erotic odes to Damayanti, the princess of Vidarbha, a region in modern day Maharashtra, in Naishadh-Charitam. He eulogizes Damayanti’s breasts, “Yauvanayoh khalu dvayoh plavakumbhau bhavatah kuchau ubhau (Dmayanti’s breasts are as large as a big water-pot so that her youth can use them as a floating device to swim across the ocean of the young age).” He adds: “Brahma, himself, held her by her waist when was constructing her abdomen. That is why there is a dimple on her back due to the pressure from his thumbs and, also, that is why there are three abdominal muscle packs, which came out of the three spaces between the four fingers of his hands. Her buttocks are large and round. Her thighs are as tapered as a banana tree; her buttocks are round like a perfect chakra.” Other examples of erotic Sanskrit poetry from this period abound, such as Bhasa’s Swapna Vasavadattam, Bharavi’s Kirat Arjuniyam, Bhavabhuti’s Malati Madhav, Ban Bhat’s Kadambari, Dandi’s Avanti Sundari Katha, Bhatti’s Bhattimahakavyam, and Bhartrihari’s Shringar Shatak, among others.

Even Hindu religious texts celebrated the sexual and erotic escapades of the Gods. Valmiki’s Ramayan, one of the holiest texts for Hindus, relates the story of the God Indra’s seduction of Gautam Rishi’s beautiful wife Ahalya while her husband was taking a bath. Indra appeared at the ashram in the guise of Gautam, pleading: “Ritukalam pratikshante narthinah susamahite, sangamam tu aham ichhami tyava sah sumadhyame (No one who wants to have sex waits till the menstruation time, O Slender One, I want to have sex with you).” After they make love, Ahalya thanks Indra, but pleads with him to leave before her husband returns, “Kritarthasmi surashrestha gachcha shighram itah prabho (I am honored and thankful, O Indra, please leave quickly).” Indra replies, “Sushroni, paritushtoasmi gamishyami yatha agatam (O lady with beautiful buttocks, I am very satisfied and I will go the way I came, very quickly). But none of these Sanskrit poets could match the erotic imagery that brims forth in Kalidas’ Kumarasmbhavam: “The rain drops fell first on Parvati’s eyelids and, then, after lingering there for a moment, they passed over the upper lip and then they fell on her lower lip where they stayed while. The rain drops scattered into million pieces when they fell down from her lower lips on her hard breasts.” Kalidas captured Shiva’s lustful playfulness with Parvati in these immortal words: “Sasvaje priyam uronipidanam prarthitam mukham anen na aharat, mekhala pranay lolatam gatam hastam asya shithilam rurodh sa (She pulled him tightly towards her whenever he embraced her; she moved closer to him whenever he kissed her and whenever he tried to untie her waistband, she pretended that she was trying to prevent him from doing so).” Such erotic playfulness, coyness and coquettishness are among the most enduring and endearing legacies of Sanskrit literature. |