Arts

Hot And Cold

The hottest new thing on Indian grocery shelves is frozen

|

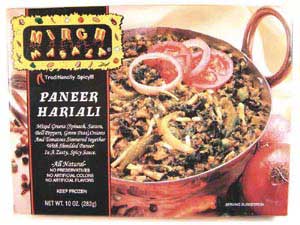

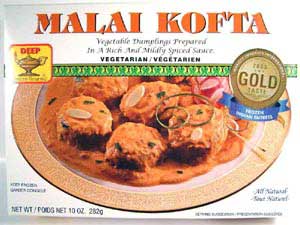

Over 22 million Indians have migrated to different parts of the world, but there’s another migration that’s taking place and few people have realized just how momentous it is. The mass migration of millions and millions of samosas, kachoris, dosas and idlis – made in India and quick frozen – delivered to your door in California, London or Dubai, almost as fresh as those made by your dear Amma! Who would have thought that there would be a virtual kitchen in your freezer? It’s indeed a Cold Revolution – walk into any Indian grocery store in the United States and you will be amazed by the variety in frozen dinners with everything from gourmet specialties like Paneer Hariyali to Malai Kofta to Uttappam. Some of the major manufacturers and distributors of frozen Indian food in the United States include Deep Foods, headquartered in New Jersey, House of Spices and Rajbhog Foods in New York, Raja Foods in Chicago, Dishanka Gourmet Imports in Texas and Kostos International in California.

Each is doing its bit in getting frozen ready to eat dinners, ice-creams and snacks to hungry and harried South Asians across America – and some are even winning over converts from the mainstream. And they are certainly Each isringing it up at the cash register – frozen foods are a cash cow. While the Indian frozen foods comprise just a small part of the multibillion-dollar American frozen food industry, the sales figures are quite respectable. According to Neil Soni, vice president of House of Spices, “Wholesalers to retailers, it’s possibly a $15 million market, while for the retailers it could be a $25 million market. It’s a good component with lots of growth opportunities.” Soni believes that with the tight scheduling of working families, time is at a premium and so the Indian market is evolving into what the mainstream consumers already expect from their supermarkets. Few mainstream customers would go to a supermarket to buy flour to make bread from scratch; in the same way many Indian consumers are skipping the raw material to get the ready-made chappatis and naans because everyone’s so time-deprived.

House of Spices is a major distributor of several brand names from India, including products like Vadilal frozen vegetables as well as ready-to-eat dinners like Vadilal’s Sarso ka Sag, Bhindi Masala, Dum Alu, Punjabi Chole, Dal Makhani and Navratan Korma. It also imports frozen snacks like samosas and kachoris under its own brand name Lakshmi, and the Lakshmi line is expanding to include more South Indian snacks, because Soni feels there is a big demand from the South Indian community which hasn’t been met. Probably the biggest player in frozen foods is Deep Foods, which actually manufactures most of its frozen items in the United States. Pressed on the magnitude of the demand frozen foods, Deep’s Archit Amin says, “You’re still going to have more basmati sales than frozen foods, there’s no doubt about it. The groceries are still the No. 1 product that people go to these stores for. What we do see a pick up in is in entrees, not as much as we’d like to see, but we do see a lot of potential there.”

Indeed, it must be hard for Indian families to give up the cultural tradition of cooking fresh food every day, but in this new world you don’t have the retinue of servants nor do you have the time to always whip up an elaborate meal from scratch, weeping as you chop the onions. Amin is quick to defend the benefits of frozen food: “Most Indian people have the impression that frozen food is not fresh and that’s the biggest misconception. I can’t emphasize that enough.” He says the freshest food you’ll find in the market is frozen unless you’re going to prepare it yourself. He adds, “Think of what frozen really is, it’s actually time-trapped and frozen. Frozen in time and you’re not going to get anything fresher then that.” For most manufact-urers of frozen food, that probably is the challenge, to convince Indian consumers that they can get a premium dish for a few dollars instead of goiing to a good restaurant for that taste. In its light hearted advertisement, Deep Foods has tried to convey that message: you see a bachelor eating a frozen dinner and as he takes each successive bite, the room is transformed into a fancy restaurant and he morphs every step of the way as he gets five star treatment.

As Indian families adapt American lifestyles with both spouses working and the children involved in scores of extra-curricular activities, there’s less time to prepare food. Says Amin, “Most households that I talk to are eating more out than not; it doesn’t have to be that way. There is an in-between way and you don’t have to spend that kind of money nor do you have to spend time cooking.” Deep Foods has a 100,000 square feet facility in Union, NJ, where it produces several lines – Mirch Masala, Deep and Curry Classics, as well as the Green Guru International Cuisine line. It also distributes other frozen food lines such as Maharani and Kawon Malaysian parathas. The company first started its frozen foods business by manufacturing Reena Cce Cream with such Indian flavors as pistachio and mango. Amin recalls, “The Indian community was growing so we realized there was a need. We recognized that more and more couples were working and had less time to spend in the kitchen.Now we get so much fan mail saying that these meals are a lifesaver.” The company, which was started in 1977, today churns out 20,000 frozen meals in each shift. “One of the newest things we are doing is we’ve actually put up a facility in India for making items that are hand-made and we are proudly employing about 300 people in Gujarat,” says Amin. So now we have the outsourcing of samosas!

Another big player is Raja Foods, based in Skokie, Ill, a suburb of Chicago. The company has been in business since 1992 and imports frozen foods from India under the Swad label. According to Swetal Patel of Raja Foods, Swad has the largest variety of frozen vegetables in the market, especially ethnic products like tindora, papdi lilva, valor papdi, chauri and tandal jo ni bhaji, which is a leafy root vegetables which is a part of traditional Gujarati cuisine. These come fresh from the farms in Gujarat and are much easier to prepare since they are already cleaned and cut. Says Swetal Patel, “All you need to do is heat your oil, put the vegetables in and ten minutes later, and it’s done. For people who are looking to make authentic dishes this is great. Fresh produce may be available here, but only in certain seasons and may be more expensive.” Another example he gives is that of drumsticks, which if fresh, could go for about $4.99 a pound, since they have to be flown in from the Dominican Republic; the frozen drumsticks from India retail from $1.39 to a $1. 99. He says, “The price point is very attractive. There are certain cities were fresh is not so easily accessible and frozen products become a solution.” The owners of Raja Foods also have a chain of Indian grocery stores and five restaurants in Illinois, and the chefs formulate many of the entrees for the frozen line. He says, “If you had the Swad Dal Makhani and restaurant Dal Makhani, you’d probably pick ours over it. Asked to identify the best-selling the products in Chicago, Patel lists the Swad frozen samosas, kachoris and the Asian Indian spring rolls – people tend to stock up on them as Diwali approaches. Currently Raja Foods is making more shelf-stabilized dinners than frozen, but will be adding several new products in a month. We’re also coming out with paneer and potato wraps. These will be great for people on the go, like college students and the taste is really good. It’s solid Indian paneer which tastes delicious.” Another player in the frozen food business is Rajbhog, Inc., established in New York, and whose name is synonymous with sweets and snacks. Sachin Mody, one of the owners, says, “For us, the frozen foods was a new line we started about two years ago, but it has significantly increased. The demand is there, basically both husband and wife are working. The younger generation has grown up and they are all working, and even the ones who are married are both working. So for them, this is a fast way to eat.”

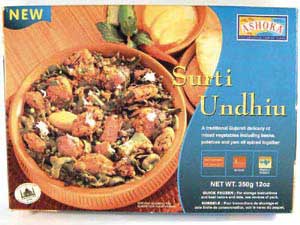

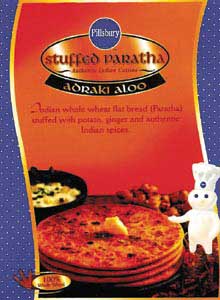

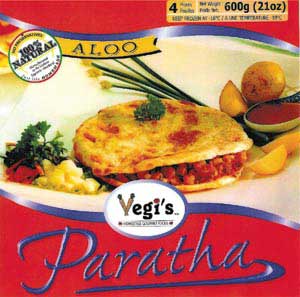

Rajbhog manufactures about 45 frozen items from matter paneer to Punjabi chole to party samosas, and all their frozen entrees and appetizers are manufactured in New York in an 18,000 square foot factory and are shipped all over the United States. Undhiyu, a traditional Gujarati item that is an authentic mix of Indian vegetables and many different beans, is one of Rajbhog’s dishes. Says Mody, “There are people who like Undhiyu, but their wives don’t know how to make it. Our whole concept when we started making frozen food was like bringing mother’s food back into your home.” Out in California, Kostos Internat-ional entered the frozen foods arena seven years ago with its Vegis brand of parathas, which until then had only been available in the form of Malaysian parathas. Vegis Homestyle Gourmet Foods include specialized breads like naan, Toast-A-Roti, paratha, chapatti, poori and flaky parathas. While some of the Vegie breads are made in an automated bakery in California, the majority of the products come from India. The lineup includes five types of naan – garlic, onion, Sher -e-Punjab, tandoori and roghani. This is a truly global world and Pillsbury, the American company, is actually making naans in India, and Kostos International is national distributor for the Pillsbury line. So why is Pillsbury’s Doughboy, usually busy with cakes and pastries, making frozen naans and parathas? Says Kostos Vice President Jay Parikh, “Pillsbury has many ethnic lines, and one of them is Indian.

Though it’s an American company, the outfit which manufactures the frozen flat breads is completely Indian. They have a factory near Bombay and they have the experts in the field of Indian food and that’s how they developed the recipes.” Pillsbury has seven frozen products coming into the United States – a ready to puff roti, spring onion parathas, layered Malabar parathas, Adraki Alu parathas, tawa whole wheat parathas, stuffed spicy alu masaledaar naan and a paneer-filled naan. That’s more variety than you see in the breadbaskets of many Indian restaurants! Kostos International distributes to 1,300 stores nationally, mostly Indian and Pakistani, and some Middle Eastern stores. Says Parikh: “We have a few mainstream outlets at the moment. Indian foods are not as famous as Chinese and other foods, but are getting known, and the frozen samosas and spring rolls are very popular.” So America is finally waking up to the joy of zapping a microwave button and retrieving sizzling malai koftas in minutes! Why so late in the day in the United States, when the Brits have long made Indian food a national favorite, available in the frozen and chilled sections of mainstream stores like Mark and Spencer’s and Selfridges? He points out that even in a cosmopolitan city like New York there might be many affluent Americans who don’t know about Indian food and don’t want to try it because they’ve never been exposed to it. He says: “I think there’s a very big opportunity, but it has to be marketed properly. Right now I find that only the younger, college educated Americans – from the ages of 18 and 25 have the most potential to try Indian food.” Swetal Patel of Raja Foods says of the chilled foods that are such a rage in London: “More than frozen, they have what is called chilled foods. When you go to the deli here in American stores you really are finding a lot of the same products you found 30 or 40 years ago. It hasn’t really evolved but in London because of the Indian influence these foods are readily available.” He says that the Indian influence hasn’t been here that long while Chinese and Italian foods have been here much longer. “Italian food finally made it to the deli counter about seven years ago and Chinese food is slowly making its way – so it’s going to be some time before Indian food make it to the chilled section. You’ve got to remember England is about the size of Illinois so to distribute food like that is simple. There’s no complication. Here’s it’s a monster, we have four time zones!” He finds that in India the frozen trend has not yet caught on with consumers and people tend to eat fresh. One of the stores he visited had just one small freezer while as he explains, all the Patel Brother grocery stores in the United States are equipped with large freezers: “As a company we’ve invested the most amount of money in freezers. Any new store we open, we put in $100,000 worth just in freezers.” The frozen food revolution is happening mainly because of great transportation, but a huge infrastructure is needed in this country as well. Swetal Patel says that a lot has to be invested in the freezers and they have 6000 sq foot freezers in both their facilities in Chicago and New York: “The initial investment in the units isn’t that much, but the cost to run them on a monthly basis can be $6000 a month.” So with all the costs and transportation, is it worth all the trouble, bringing frozen foods in from India? Says Swetal Patel, “Oh, yeah, why not? Everyone’s still making a profit. Trust me, it would have been dead in the water if it weren’t profitable!” Has he thought of selling to the mainstream? He says, “Raja Foods is a company which sells to many supermarkets in the country – Whole Foods, Jewel and AP. However the whole frozen aspect as a business is new to us and selling frozen to supermarkets isn’t as easy as everyone thinks. It costs more to do business with supermarkets.” The company has warehouse and freezer facilities and partners with various distributors selling every brand from Ashoka to Deep Foods and Pillsbury. The main alliance is with Dishaka Gourmet Imports in Houston, who are the manufacturers and distributors of Chirag brand of food items. So we’ve developed a process where people can contact us off our website and we have people on our staff who will actually walk the customers through the ingredients and the processes in which they can use the foods.” I think there will still be time needed for the adaptation process to happen, because there are so many grocery stores for Indian products in American cities now.” Asianfoodcompany.com finds more potential in the affluent mainstream market that chooses to look at Indian food as gourmet. Patel says that in the course of a year, business has grown risen ten fold. He adds: “We see a lot of business for frozen food, currently it accounts for 40 percent of what we send out. It’s popular with the mainstream; they’ve had Indian food in restaurants and they’d like to be able to recreate it at home but if they can’t, the next best thing is to be able to buy it.” Presently most of the frozen entrees are vegetarian but Deep Foods’ Curry Classics line has several chicken entrees too, including chicken curry, pad thai, basil curry, samosas as well as Tandoori chicken with spinach. Considering that India has such a vast variety of non-vegetarian and seafood dishes, the surface has barely been scratched in replicating these for the frozen sector. Interestingly enough, all the large manufacturers that Little India spoke to have the second generation involved in the family business – and surely these American born and educated entrepreneurs will be all the more receptive to innovative ideas and new challenges. So the next time you’re on deadline and have no time to cook and don’t have the desire to eat yet another turkey sandwich or slice of pizza, holler for your invisible personal chef. No need to chop and cut; all the exercise your fingers have to do is open up the boxes and zap the microwave button. Huge succulent samosas stuffed with cheese and jalapeno peppers, plates of steaming daal makhani, palak paneer and an array of crisp parathas, rotis and naan. Or perhaps you’d prefer fluffy idlis, golden dosas, uttampams and some spicy rasam? No problem, it’s all in the box. Spread out your fit for a king feast on the dining table and then say a silent prayer of thanks to your Indian grocer! |