Arts

GOD (Awful) Actor

It is important to remember that Amitabh is a star, despite the BBC poll of the Millennium that accuses him of being an actor.

| Every desi has been a victim of Bollywood’s charm. Some experience goose bumps; others dismiss the industry as lowbrow. In fact, to take a position on Hindi movies, or what has come to be called Bollywood, is to find and assert your own position on the culture divide.

Stars in the film industry are created for their glamour and entertainment value. We are all caught up in its eternal charm without asking ourselves if it has any connection of reality. It is hard to complain, because it is easy to be one with the dreamy world and too harsh to wake up. Amitabh Bachchan has ruled the world of stardom in India for over four decades. A BBC poll on the star of the Millennium voted him at the top, besting Lawrence Olivier, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and even Govinda! The best star of the last 1,000 years! Surely the phenomenon warrants our attention.

Amitabh has won higher accolades, actually. Many have called him God already, and surely we can’t do better than that! Several contestants at his Kaun Banega Crorepati? an Indian franchise version of Who Wants to be Millionaire?, were less fervent about becoming a crorepati as they were about wanting to touch his feet or simply be in his presence. Sharing the stage with him allowed them just that privilege. It was darshan of god. For those who came to the United States before the 1980s, his name means little and they can rightfully wonder what the hullabaloo over him is all about. Those who arrived later watched his early films and contributed in some ways to his popularity. To most second generation Indians or recent immigrants, he is a “has-been,” but notwithstanding the rise of the newer stars, his appeal ensdures. The cultural critic Richard Dyer once wrote that stars are created to cushion us against harsh social realities and to make identification with good possible. They are also vehicles to our desires, ones that cannot be unloaded easily in our personal lives. That is why, for years, we have the intellectually inexplicable appeal of Marilyn Monroe, who gave this country (and the rest of the world) a sense of idealized female sexuality for over five decades. It is easier to take her into the private temples of worship than deal with the reality of our everyday lives. Amitabh did exactly that. Among all the reasons for his enduring fame, perhaps the most central is his appeal to Indian masculinity. Most early Indian male stars, from Bharat Bhushan and Dilip Kumar to Dev Anand and Rajesh Khanna, were crying, moaning melancholy wimps. They did little to channel our masculine desires, other than run around trees and weep or sing in difficult situations. They had to have a woman and the main pursuit of their lives was to satisfy two arch-women in the lives of Indian men, their lovers (wives) and their mothers. Outside of these women, the men and their stars had little existence. We were beaten by China in a war, got into bloody fights with Pakistan, could not win any medals of any kind on the international stage and the best man we had was our prime minister, who actually was a woman.

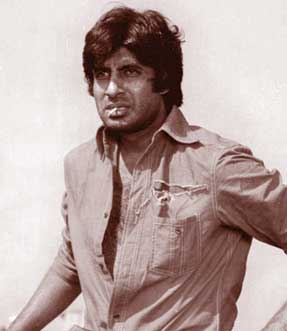

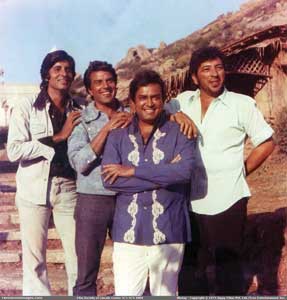

Amitabh arrived on the scene in mid-1970s and knew how to “kick ass.” He was a real man, who was odd looking (like the rest of us), had a physique that was hardly romantic, knew how to get into a brawl and had a voice that was deep and yes, manly. He got angry with the gods, he knew how to get drunk and make an adorable fool of himself. He knew city life well and looked completely at home in it. He did not chase after women. He was comfortable being a loner. His most frequent co-star at the time, Parveen Babi, was more like him than the chaste bahus that walked into our dreams. She smoked and she was a loner too. She did not mind going to night clubs and there was everything urban about her. All things bad in Indian life came from urban life and the two of them carried it well. You could not fit Talat Mahmood’s voice onto this fella, lovely as Talat has been all along. Awkward but timely for the needs of manhood in a culture deprived of it for a long time, Amitabh achieved his fame not because of the inherent quality of his work, his results. One presumes it was easier for audiences, the proverbial “masses,” to identify with him. And they did. Amitabh hits kept coming and acquired their own formula. The stars that came after him, from Govinda to Shah Rukh Khan, followed his formula for the most part, mixing some other elements of the complex Indian manhood into their stardom. Actors rise to their scripts, stars mold the scripts, often leave them out to hang, and use them to enhance their own public image. Stars are stars in all films while actors are different. They get wider acclamation for their work. They last longer, even longer than online polls, which are populated by people who have too much time on their hands. Once Amitabh realized that his persona attracts audiences, he refined it, honed his skills and made sure that he carried himself publicly and visibly to fit the image of a star. From Dewaar (1975) to Mukkadar Ka Sikandar (1978) or from Don (1978) to Amar, Akbar Anthony (1977), it was always Amitabh, with some variations in scripts, locations and the babes who made his life tolerable. No wonder movies are considered “star vehicles” and not acting opportunities. It is a shame, really, that this able human being, perhaps more literate than most of his early predecessors or his contemporaries, was so shaped permanently by the tastes of Bollywood. Despite making millions, he did not take much risks, not so much in his image (because that was teflon all along) but in his acting abilities.

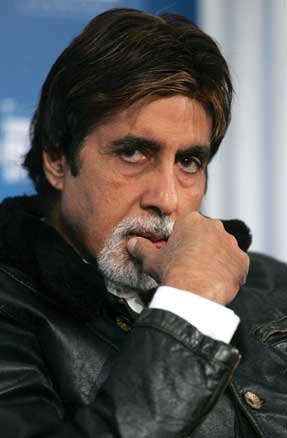

He is omnipresent in India. Once a member of parliament, a controversial owner of land, an investor with ambitions both at home and abroad (including here in the U. S.), a father-in-law of another attractive material from Bollywood, father of a son who sticks to his coattails, a divine presence at most events and god permitting, when he appears on the street, Amitabh can be found everywhere. When he catches a cold, the whole country shivers. There are lines outside the hospital where he is recuperating and temples invoke the Gods to render this God whole. His voice plays a large part in what we think of Indian popular culture today. He is everywhere, from commercials to commentaries at temples and holy places. In a country with millions of gods, he is another addition. And no one minds it at all! Amitabh offers an opportunity to examine ourselves, deeply and seriously. The fact that television sustained his fame and in some ways returned it to him after some hiccups in his career simply underscores the fact that the culture likes to embrace the phenomenon regardless of the quality of the experience. One should not complain because the audience he commands tends to neutralize any critique of him. May be! Usefulness can lull us in sleep and meaning keeps us awake!

It is important to remember that Amitabh is a star, despite the BBC poll of the Millennium that accuses him of being an actor. After a while, he got settled into being himself on screen. And we went to see how he looked in his new role instead of for his acting potential. The myth of Amitabh’s acting prowess is a problem of confusing the power of his presence on the screen with the attendant help he gets from the camera, some gifts of script and the publicity machine that makes him look larger than life. Consider Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Black (2005), which shows Amitabh’s painful attempt at depicting a stage of Alzheimer’s. It is a role that cannot seem to convey much more than a few gestures from a good actor and yet Amitabh repeats the same tantrums for a long time. The Guardian newspaper in the U. K. recently dubbed his most recent film The Last Lear (2008) the most “god-awful film ever.” These observations may seem sacrilegious directed at the god of acting or the best actor of the Millennium, but most of us have the need to carry the myth in our minds. After all, it makes the reality much less harsh. |

You must be logged in to post a comment Login