Books

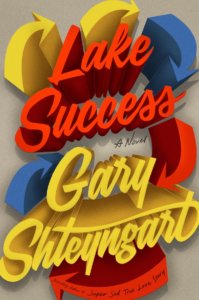

Gary Shteyngart’s ‘Lake Success’ a Comic Tale of a 1-percenter

Gary Shteyngart

Photo: Brigitte Lacombe

Lake Success is often satiric, deploying the same sharp skills as Shteyngart's earlier novels, like Super Sad True Love Story and The Russian Debutante's Handbook

One night young lawyer Seema Cohen went to a Vogue party hosted by billionaire Michael Bloomberg and there met the man who would become her husband. At first, she wasn’t sure she liked the glad-handing middle-aged hedge fund guy who was clearly smitten with her.

So “she went home and Googled Barry’s net worth and found it comforting. A man that rich couldn’t be stupid. Or, Seema thought now, was that the grand fallacy of twenty-first-century America?”

That’s a central question in Gary Shteyngart’s terrific new comic novel, Lake Success, as it follows 1-percenter Barry Cohen on a quixotic Greyhound bus ride across America in flight from his family, at the surreal height of the 2016 presidential campaign and election.

Lake Success is often satiric, deploying the same sharp skills as Shteyngart’s earlier novels, like Super Sad True Love Story and The Russian Debutante’s Handbook: a cool control of tone, a Tom Wolfe-level eye for status markers, a knack for making the outrageous sound all too plausible.

But Lake Success has depths. Barry might be the oblivious poster boy for white male privilege, but Shteyngart makes us feel for the people around him, especially Seema and their son.

That son, a beautiful 3-year-old named Shiva who has never spoken a word or looked another human being in the eye, is the bond and the breaking point of Barry and Seema’s marriage. Both are strivers. Barry, a non-observant Jew, grew up in Queens, raised by a father who ran a pool service, his mother dead in a car crash when he was 5. Seema comes from Cleveland, the daughter of immigrants from India; she has a law degree but shrugs away from working after she marries and has a child.

At first their carefully curated marriage is as dreamy as the vista from their vast Manhattan apartment, with its view from above of the Flatiron Building and, above them, a penthouse owned by Rupert Murdoch.

But when Shiva receives what they call “the diagnosis” — he’s on the severe end of the autism spectrum — curation fails.

The novel opens with the events that send Barry to the bus following a dinner with a couple who live in their building. She’s a doctor, he’s a novelist Barry’s never heard of, but Seema admires his books.

“A writer? In their building?” Barry thinks. “Where even the one-bedrooms with a view of the back side of a taco joint started at three million? Something about that didn’t sit right with Barry, but he let it go.”

When the writer turns out to be a suave and sexy Guatemalan, Barry, no stranger to male dominance displays, goes upstairs to fetch a $33,000 bottle of Japanese whiskey from his collection.

The whiskey is guzzled, the dinner ends badly, and when Barry and Seema go upstairs things get worse. After a physical altercation with his wife and Shiva’s devoted nanny, Novie, he takes off.

Barry packs a bag with “a fistful of underwear” and the contents of his “Watcharium,” his beloved collection of timepieces. Nothing so vulgar as a common Rolex; these are rare and pricey items, and the only possessions he thinks to bring along:

“He couldn’t do this without the watches. He couldn’t live without their insistent ticking and the predictable spin of their balance wheels, that golden whir of motion and light inside the watch that gave it the appearance of having a soul. … The watches would help Barry stay in control.”

Making a Dante-esque descent into the Port Authority Terminal, Barry sets out to find his Beatrice, a.k.a. his college girlfriend. Layla Hayes is now living, Facebook tells him, in El Paso. Before he even boards the bus, he jettisons his smartphone. It’s not long before his Amex black card is gone, too, leaving him dependent on the kindness of strangers and long-lost acquaintances.

Although Barry despises Luis Goodman, the Guatemalan novelist, he fancies himself a literary man, what with his minor in creative writing at Princeton. He thinks of his journey in novelistic terms, comparing himself to Hemingway and Fitzgerald and, in a breathtakingly tone-deaf moment, dreaming of writing about his trip as Kerouac did: “On the Road but in thoughtful middle-aged prose.”

In short, he’s the star of his own movie, as he has always been. He blithely mooches off people with far fewer resources than himself and is shocked when some of them, with good reason, rebuff him.

After stops in Richmond and Baltimore, he visits a former employee, Jeff Park, now living happily in Atlanta. Jeff was fired after making a typo that cost Barry’s hedge fund millions, but he’s still a numbers geek: “The average girl I date is five foot six, or an inch taller than the national average,” he tells Barry. “I have a spreadsheet that lists the attributes of each girl I’ve ever dated. It’s super granular.”

They hang out, but when Barry asks for a “bridge loan,” Jeff turns him down, for reasons reminiscent of the Pharma Bro case — Barry invested hugely in a company that jacked up the prices of lifesaving medications, including one Jeff’s father takes.

It’s just one of the encounters Barry has with people who are feeling the effects of political change, even before Trump has been elected. Not that Barry himself supports the man, even though many of his wealthy friends do.

“Barry had only learned to hate Trump,” Shteyngart writes, “after he had made fun of a disabled reporter at a press conference, fluttering his arms around in imitation of his affliction. Shiva did the same thing — ‘flapping,’ it was called — whenever he tried to express some great unspoken pleasure. Anyone who could make fun of one of his son’s few private joys didn’t deserve to live.”

But the Trump effect seems to go right over Barry’s head when he reconnects with Layla, now a college professor, and discovers that she’s being trolled horribly by Nazis online because she teaches a class on the Holocaust — they’re even threatening her 9-year-old son, with whom Barry (briefly) bonds.

The reunion with Layla goes bust after a nightmarish trip to Mexico, and Barry rolls on toward La Jolla, where his father, a former Democrat, has succumbed to the zeitgeist, sporting a MAGA hat in his retirement: “Barry was a moderate Republican, and his father was a moderate Nazi. They were a moderate family.”

Shteyngart alternates chapters about Barry’s travels with Seema’s life in Manhattan. She tumbles into an affair with the Guatemalan novelist, but quickly realizes that leaving one narcissist for another isn’t a great plan.

She’s so furious with Barry she doesn’t even try to find him; instead, she comes to focus on her son. Her relationship with Shiva is in many ways the opposite of Barry’s: He flees a problem that can’t be solved by throwing money at it, while she refuses to give up on her boy.

Shteyngart writes with humor and empathy about Seema’s efforts and doubts: “Each time Seema saw a gaggle of teenagers sitting cross-legged, absorbed in their devices, tuned out of one another’s physicality, she wondered if the world to come would be slightly more hospitable to Shiva’s condition.” And his depiction of the relationship between the boy and his grandfather after Seema’s parents move in is simply lovely.

Barry’s journey, and Seema’s and Shiva’s, take unexpected turns. Shteyngart’s satire raises timely questions about the state of our nation; his humane story of a family offers answers.

Contact Colette Bancroft at cbancroft@tampabay.com or (727) 893-8435. Follow @colettemb.

Lake Success

By Gary Shteyngart

Random House, 338 pages, $28

Times Festival of Reading

Gary Shteyngart will be a featured author at the 2018 Tampa Bay Times Festival of Reading on Nov. 17 at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg.

©Tampa Bay Times

You must be logged in to post a comment Login