|

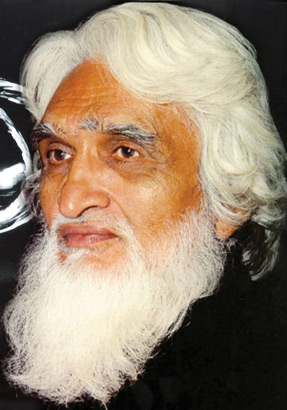

For several decades, the wiry white-haired Maqbool Fida Husain has

pranced barefoot across India and across the Indian art landscape in a more

metaphoric sense, brandishing his giant-sized brush with characteristic panache

and antagonizing the hell out of some people. Along the way, the former

tailoring apprentice and painter of Bollywood marquee-boards has earned for

himself the iconic status implicit in sobriquets like “The Barefoot Picasso of

India” — as well as a financial fortune that remains the envy of his less

flamboyant peers.

My philistine radar first caught him off the media spotlight in the

1970s. Of course, one had heard and read about him cursorily as a leading

painter in the pantheon of the country’s top-notch artists. But I recall being

quite taken in by the news story about a five-star hotel throwing Husain off the

premises because he’d entered its lobby wearing no footwear. Was this man just

another publicity-seeker? Or was he a true-blue iconoclast — masquerading as a

cheery anorexic Santa Claus, if you will — who dared, even if symbolically, to

highlight the country’s rich-poor divide by a simple act of civil disobedience?

Whatever the answer, he had managed to tickle my curiosity about his art.

|

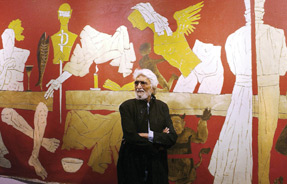

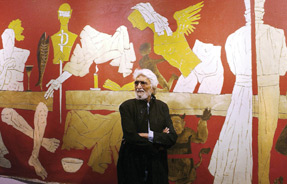

M. F. Husain stands against one of his paintings titled “Last

Supper” at the National Art Gallery in Mumbai in 2004. |

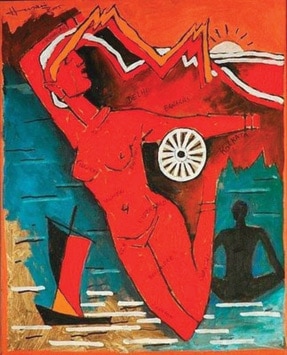

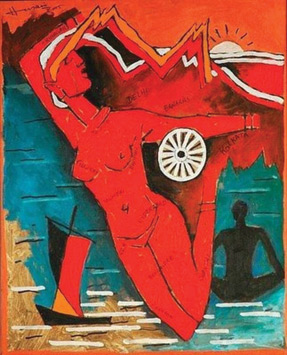

For those like me, utterly ignorant of the intricacies of art — and

especially, of modern art — his personality was a good enough key to pry open

the Husain ouvre for our low-brow art appreciation. Some traits were

unmistakable even if you were no aesthete. His broad strokes were bold and

confident — even muscular — in piquant contrast to his own physique. And there

was something riveting in his choice of stark non-pastel colors, as if the

propagandist in him was yelling out for the world’s attention. That’s how one

has come to decode Husain’s works — as top-of-the-line poster art, always but

always making a clear and preferably provocative statement.

I say “works” advisedly. Because he sometimes kept aside his canvas and

opted for unconventional media. Who can forget Husain’s experiment of using the

sides of his car and the flanks of a real-life horse as surfaces for his line

drawings? Or the time he stuffed a Mumbai gallery with old newspapers, so

visitors to the “exhibit” ended up stepping on and swishing their way across

reams of carelessly strewn newsprint? Or his quirky and personalized

documentary film — aptly titled Through the Eyes of A Painter — which won him a

Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival.

Was he, in the first instance, drawing temporally removed yet similar

parallels between modes of transport and mediums of artistic expression? And

making a sharp editorial comment, through the second, on the ever-increasing

and ultimately meaningless information-overload that modern media outlets are

subjecting us to? The art critics tore their hair out in frustration. There was

no way to categorize these upstart antics from a seasoned veteran. Worse, there

was no verbal explanation forthcoming from the master himself — except for that

grin and that twinkle in his eyes.

|

Many in my generation loved this approach. To hell with the stuffy

notions of art theory that rendered the contents of art galleries elitist and

inscrutable. Unlike his contemporaries whose works looked opaque, esoteric and

distant to the uninitiated, here was an artist who succeeded thoroughly in

connecting his Muse to the common-man’s consciousness. Who was making millions

selling his paintings to the filthy rich without losing touch with the grime of

everyday living. Who had made Art so much a part of Life — and vice versa.

Bolstered by his reportedly bohemian lifestyle and his ever-youthful

demeanour despite his advancing age, Husain’s public persona meanwhile grew

angelic wings. He was metamorphosing into a Sufiana artist of sorts, a man for

whom painting seemed a chhand (a most fitting Indian word for sublime artistic

passion that brooks no ties with mundane worldly commitments) rather than a

money-making craft or vocation.

Over the years, other stories grew as well. Husain as prolific, almost

assembly-line, creator (his output is said to have crossed the 10,000-mark);

Husain as billionaire (his mere signature is said to bring in millions); and

finally, Husain as closet-renegade and communalist.

The last was disturbing stuff. Who ever imagined that this

chhand-driven maverick rebel-artist could so easily worm his way into the good

books of fascist Emergency authorities by painting glowing portraits of the

then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi as Goddess Durga — and not, as I recall, in

the nude — at a time when several crusaders of free speech and artistic freedom

were languishing in her jails? The Sufiana sheen was wearing off.

And how many people in a Hindu-majority nation like India would take

kindly to a Suleimani Bohra — born into a Shia Muslim sect with close links to

Hindu philosophy and rituals, and hailing from the Hindu temple town of

Pandharpur in Maharashtra state — who depicts their gods and goddesses in the

nude, with the latter copulating with animals? Hadn’t his background sensitized

Husain to the spiritual core and depth of Hindu mythology? Had the artist

vitiated his chhand by over-stepping into the realm of malicious mischief?

A sizable number of Indians believed he had. Between 1996 (when a Hindi

magazine Vichar Mimansa first published a set of Husain paintings) and 2006

(when the Supreme Court of India consolidated and transferred all the cases to

a Delhi court for adjudication), nearly 900 civil and criminal cases were filed

against M.F. Husain in courts throughout the country. The more hot-headed among

his detractors — notably those affiliated with the right-wing extremist Bajrang

Dal group — vandalized an Ahmedabad studio exhibiting Husain paintings, while

others even broke into the painter’s Mumbai residence.

|

|

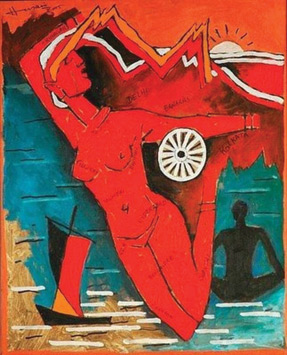

Delhi High Court: The nudity in the depiction of Mother India had purely metaphoric overtones. |

Curiously, the decade (1996-2006) saw the advent of Hindu

fundamentalism in India paralleling the rise of Islamic terrorism across the

world. The Husain saga served to highlight both trends, and also showed up the

competing communalism that resulted. Soon after a Muslim politician in Uttar

Pradesh offered Rs 5.1 million to any person who would assassinate the Danish

cartoonist Kurt Westergaard for planting a bomb-shaped turban atop an imaginary

Prophet Mohammad, a Hindu reactionary came up with a Rs 10.1 million offer for

killing Husain.

Fearing for his life, Husain fled to the Middle East and has remained

there ever since, venturing out occasionally to London for his summer

vacations. Earlier this year, Husain was conferred Qatari citizenship by the

Emirate. It has led to some soul-searching among those concerned with artistic

freedom and its limits, and stirred up a debate among those who believe in

varying degrees that art must be responsive — even subservient — to the social

order. More pointedly, what do the events involving Husain and other artists

(see sidebar) portend for the future?

There are obvious reasons why that debate centres primarily on M.F.

Husain, why l’affaire Husain has become a test-case of India’s religious

tolerance and artistic liberty. For one, he is the most visible, recognizable

and durable symbol of modern Indian art. Any fetters on the man — who many believe

is beyond doubt a national treasure and an institution — are bound to create a

flutter well beyond the local art community. For another, no other Indian

artist in living memory has tested the limits of creative freedom by taking on

the task of depicting — in the most controversial manner possible — the deities

of the country’s majority religion. And finally, at least to some extent,

because he is a Muslim. Let’s face it. Husain may have pushed the frontiers of

artistic gumption much too hard, but Indian-Hindu artists down the centuries

and in the modern era too have tested the waters of mythological interpretation

through the visual arts. They may be lesser known, but their work — although

much less daring or brazen — is no secret.

The debate also stirs up interesting counter-points. Whereas an

ostensibly beleaguered Husain chose self-imposed exile in the authoritarian

regime of Qatar, citing rising intolerance from the Hindu fundamentalists in

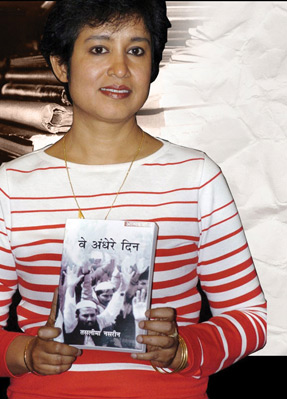

the land of his birth, Taslima Nasreen — a Bangladeshi writer and, like Husain,

a Muslim — preferred that same land as a refuge from Muslim fundamentalists

back home. She now faces a backlash from the Muslim orthodoxy in India.

Nasreen’s predicament serves as a neat foil, mirroring the tribulations faced

by Husain for taking artistic liberties with religious beliefs. She has been

hounded for critiquing the tenets of the Holy Quran and for denouncing Islamic

practices like the burqa which, in her opinion, objectifies and debases Muslim

women. If a Husain exhibition in Gujarat state invited vandalism, a Nasreen

article in a Karnataka publication sparked riots that killed two.

|

But, unlike Husain who was conferred with the “honor” of Qatari

citizenship by the Emir himself and today sits ensconced in the lap of material

comfort and luxury, Nasreen, a trained doctor and social activist, has been on

the run since the publication of her first major work — travelling to and

hiding in various cities within India as well as in Europe and USA — without

adequate security or any assurance from the Indian Government which has cruelly

kept her on tenterhooks with virtual house-arrest and time-bound extensions of

her resident permit.

The crucial difference however is that Nasreen has shown her pluck in

storming the citadel of her own co-religionists who have responded with fatwas

against her and worse: she was all but assaulted and manhandled by a mob of

Islamic fundamentalists in Hyderabad. Contrast this with Husain. When he

undertook in 1968 to paint 150 canvases of Ramayana stories at the behest of

socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia, conservative Muslims from that same city

approached the painter to work on Islamic themes. Husain backed out with the

defence: “Does Islam have the same tolerance? If you get even the calligraphy

wrong, they can tear down the entire screen.”

So, has India really failed M.F.Husain? To be sure, the Indian

executive branch’s performance has been abysmal. You’d think that the currently

ruling Congress Party — with its long history of avowed sensitivity toward

Muslims — would fight to protect an artiste of international renown and stature

who hails from a minority community. Quite the opposite has happened, as Husain

himself observed in a media interview in which the 95-year-old painter said he

actually felt safer under a BJP government.

Events bear him out. The Congress-led federal government has at no

point pressured state administrations to prosecute the rioters who vandalized

his house and paintings. Instead, reports now reveal that it issued a secret

internal-advisory based on the Law Ministry’s review of Husain’s paintings that

“appropriate action” should be taken against the artist — whom it had nominated

to a prestigious parliamentary seat in 1987, but who is now a political

hot-potato —to fend off potential communal trouble.

The two-faced policy continues: Hours after news of the Qatari offer

and its acceptance trickled in, India’s Home Minister P. Chidambaram promised

Husain “full security” if he returned home. Will these politically correct

offers sway his decision? Extremely doubtful. Husain is hardly the sort to feel

comfortable with stern-looking Black Cat commandos shadowing him round the

clock.

In contrast, the country’s judiciary has been bolder. In May 2008, the

Delhi High Court quashed most of the frivolous suits against Husain in what has

been widely trumpeted as a “landmark” judgment. In truth, the judgment is not

quite as sweeping. Confronted with the task of adjudicating on the “alleged

obscenity” of a Husain painting titled Mother India Nude Goddess, the Court’s

decision had, by its very nature, a necessarily limited scope and focus.

Husain’s supposed denigration of Hindu gods and goddesses by their

“obscene” depiction in various paintings — the main bone of contention against

the artist — was never made an issue by the anti-Husain litigants. Instead, the

case revolved around a single painting where the painter’s intent on hurting

the feelings of Indians by an “obscene” representation of Mother India became

the sole matter of adjudication. Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul ruled — in a

74-page judgment which recounted the legal history of obscenity cases across

continents — that there was no deliberate intention on the artist’s part to

hurt the feelings of his fellow citizens and that the nudity in the depiction

of Mother India had purely metaphoric overtones. Moreover, since only

nationalistic feelings — and not religious feelings — were involved, the second

charge of hurting religious sentiments was rejected, as was the third claim of

defemation.

Instead, Justice Kaul denounced Husain’s critics: “It is most

unfortunate that India’s new ‘puritanism’ is being carried out in the name of

cultural purity and ignorant people vandalise art,” adding that “a painter at

90 deserves to be in his home — painting his canvas.” The judgment reassured

Indian artists and assuaged their immediate fears: it held that the criminal

justice system should not be invoked to harass them. Kaul’s advice to Husian’s

critics: if you’re offended, simply shrug it off or, at most, protest

peacefully.

|

The bigots who attacked Husain are hardly likely to to persuaded of

Kaul’s sage counsel. That they agitated violently against his “objectionable”

paintings decades after they were first exhibited shows their protest has more

to do with realpolitik than good-faith grievances. The Kaul judgment does not

cover threats to art galleries who anticipate vandalism from the religio-moral

police and invariably prefer the peaceful way out by withdrawing the

controversial works. Truth be told, this potentially has a far more invidious

and withering — if indirect — impact on artists who, faced with the prospect of

an endangered livelihood, are forced to resort to a chilling self-censorship.

India’s civil society, in turn, faces the question: Do we really want our

artists to keep looking furtively over their shoulder before every brush

stroke, and then submit their works to an extra-constitutional politically

motivated censor before every exhibition?

The answer would — and should — be an emphatic no. I am sure that a

commitment to artistic freedom is shared by all but the most regressive and

lunatic fringe of any civilized society. I’m equally sure that a civilized

people will embrace readily the concept of artistic responsibility, and so

allow anyone genuinely aggrieved by a piece of creative art to turn to a court

for redressal. That is what the Constitution and the laws provide. And to

reassure those who fear a shower of harassment suits, let me reassure them that

Indian courts are well-equipped to discourage frivolous litigation.

The real problem however arises when it comes to apportioning this

right of artistic freedom. Why do some of us make it available so readily to a

painter who sketches nude Hindu goddesses, and then deny it to a cartoonist who

caricatures Prophet Mohammad or to a writer who decries anachronistic Islamic

practices? Shame on this motley mob of pseudo-liberal secularists which blindly

endorses, celebrates and deifies M.F. Husain, while denouncing the likes of

Nasreen and the European cartoonists Kurt Westergaard and Lar Vilks.

Here is a telling example of this hypocrisy. What did the Chennai-based

newspaper baron-editor of The Hindu, who lets his leftist leanings hang out in

his editorials, do when Husain was summoned to Court for a suit against his

paintings? He accompanied the painter, in a touching display of moral support.

What did he do when informed of Husain’s Qatari citizenship? He wrote a

remorseful piece on the “tragedy of Indian secularism.” Yet how did The Hindu

editorialize the plight of Nasreen and the Prophet cartoonists living under a

perennial death-threat? “Freedom of expression is supremely important. But

surely it does not require its champions crassly to cause offence to the faith

and belief of an identifiable group.”

What blinds these opinion-leaders to the obvious realities surrounding

them? Can they ever reconcile this profound moral contradiction?

I really have no grouse against Husain merrily sketching a nude Hindu

goddess. I understand, but can never accept, the ire of my fellow-Hindus who

are provoked and even offended by the artist’s audacity of scribbling alongside

the goddess’ name, as if to rub in the point. Simply because I believe Hinduism

is just too resilient and all-inclusive a philosophy to be dented by real or

imagined slights from any artist who might want to caricature its deities out

of love or spite. A religion that willingly accepts atheists into its fold,

that assimilates and therefore validates so many diverse streams of thought and

belief, whose mythology is peopled by gods and goddesses with human frailties

can surely laugh at itself. And that may well be the secret of its longevity.

Which is why I share some of the loss on M.F. Husain becoming a Qatari

citizen. A Husain residing permanently in India, painting nude Hindu deities,

and still trotting jauntily along Mumbai’s Marine Drive without any fear or

care in the world would be the ideal antidote to our growing culture of

narrow-minded prudery, and the ultimate living symbol of our traditional

tolerance and freedom.

|

Artistry in chains

Some other examples of artistic freedom that faced the shackles of

India’s religio-moral police.

Marathi playwright Vijay Tendulkar’s Gidhade (1970) and Ghashiram

Kotwal (1972) were targeted by Shiv Sena for their sexual and political

content.

Vadodara art student Chandramohan spent several days in jail in May

2007 after being charged for exhibiting works within his art school that

“promoted enmity between different groups on grounds of religion.”

Parzania, a 2005 film portraying the story of a family caught in the

vortex of violence during the Gujarat riots of 2002, was banned in Gujarat

following pressure from right-wing Hindu activists.

Shiv Sena goons objected and nearly stopped the Mumbai performance

early this year of a Pakistani play Sara, where the heroine defies conventional

sexual morality.

In 2004, group calling itself Sambhaji Brigade attacked Pune’s

Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute and destroyed irreplaceable and unique

objects of historical and literary importance because part of the research for

a controversial biography by historian James W. Laine titled Shivaji: Hindu King

in Islamic India was conducted there.

Film-maker Mani Ratnam’s Bombay, with the city’s 1992 riots as its

backdrop, was released in 1995 only after it was seen and approved by Shiv Sena

honcho Bal Thackeray.

Sangh Parivar activists in August 2003 disrupted the performance of Habib Tanvir’s play Ponga Pandit, which critiques the caste system.

Activists from the same group forced Canada-based Indian film director

Deepa Mehta to abandon the 2000 shooting of Water in India because it discussed

the lives of widows under Hindu orthodoxy.

South Indian actress Khushboo was slapped with 22 cases from various

complainants after she endorsed pre-marital sex in a media interview in 2005.

The Indian Supreme Court dismissed all the cases in March 2010.

|

|