Arts

Firebrands Who Forged a New Art for a New India

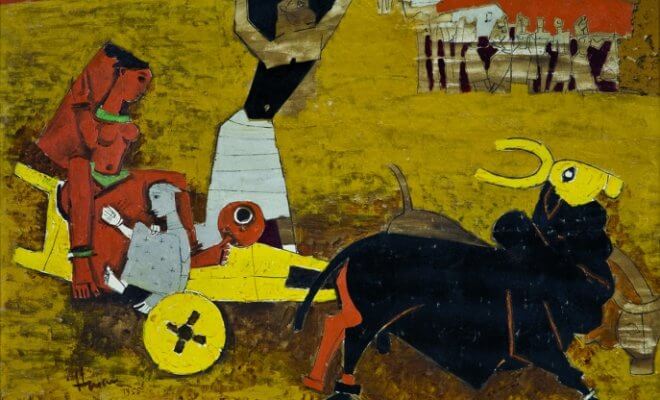

Photo: M. F. Husain. Yatra,1955. Oil on canvas. H. 33 1/2 x W. 42 1/2 in. (85.1 x 108 cm). Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi. Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi. Asia Society

The progressives founded in 1947 castigated the academic style taught at British art colleges, vowing to create a “new art for a newly free India.”

When I was a student of art history, the textbooks offered a simple, tidy and wrong story of painting after 1945. The first years after World War II were taught as a clean baton pass from Picasso to Pollock: The New York School led the way; Europe got a brief and sometimes sneering look; and begrudging attention was paid to the avant-gardes of just a few rich non-Western nations (the concretists of Brazil, the gutai artists of Japan).

Slowly, too slowly, museums are now taking up the task of rewriting the history of art since 1945 as more than just a “triumph of American painting,” as the veteran critic Irving Sandler called it. That kind of revision was the animating force of “Postwar,” the epochal 2016–17 show that Okwui Enwezor curated for the Haus der Kunst in Munich, and the last few years have also included significant shows of postwar painting from Cuba, Mexico, Poland, the Soviet Union, Turkey and South Korea in Western museums and galleries. It’s the animating force, too, of “The Progressive Revolution: Modern Art for a New India,” a new exhibition at Asia Society that showcases the leading avant-garde painters of India in the first years after independence. From 1947 to 1956, in the roiling atmosphere of post-Raj Bombay (now Mumbai), the dozen or so painters of the Progressive Artists’ Group, drawing on sources from Asia, Europe and the United States, forged a rebellious, forward-looking new style that could serve as the artistic model for a new, secular republic.

They would hang onto their restlessness long after the group disbanded. Some remained in India; others went to London and Paris; but all of them painted with a cosmopolitanism seldom accounted for in Western textbooks and Western museums.

Some of the dozen artists here are familiar to New York audiences; the abstract painter V.S. Gaitonde, for one, had a small retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in 2015, while the artists M.F. Husain and Tyeb Mehta now command million-dollar amounts on the auction blocks of London and New York. Others are little-known in the United States, and this is the first American show in more than three decades to examine the progressives’ entire collective postwar output, as well as their later, independent careers.

The progressives were founded in 1947, a few months after India’s declaration of independence and its partition, and in their manifesto they castigated the academic style taught at British art colleges, vowing to create a “new art for a newly free India.” They favored bold, fractured depictions of bodies rather than the elegance of the earlier Bengal School, making use of hot color and melding folk traditions with high art.

Several paintings here at Asia Society appeared in the progressives’ first real show in 1949, at the Bombay Art Society. Husain, the most interesting Indian painter of the first postwar years, contributed an untitled painting of a woman before a mirror, whose turbulent reds, golds and greens may put you in mind of Gauguin, or of Indian film posters. F.N. Souza, the prickliest of the progressives, painted a pair of lovers whose colorful body parts pop out of thick black outlines.

The painters came from different castes, different regions and different faiths: Hindu, Muslim and Roman Catholic. What they all wanted, as they discussed during walks along Marine Drive or over dinner at the Chetana restaurant (Mumbai’s answer to the Cedar Tavern, and still in business), was an art that embodied the potential of a secular India, with one eye on local matters and the other on the globe.

Sometimes that art took the form of direct social engagement: Souza and the painter K.H. Ara brought rare psychological acuity to paintings of beggars, while Ram Kumar’s “Unemployed Graduates” (1956) depicts four young men in Western suits too big for their famished bodies, their bulging oyster eyes pleading for recognition. Husain, by contrast, propounded a more mythological art, as in his magnificent painting “Yatra” (1955), a country scene whose bull, monkey and washerwomen drew equally from Mughal miniatures and the outlined figures of later Picasso.

One goal of Asia Society’s exhibition is to combat the abiding prejudice that accounts for these painters’ absence from my introductory art history textbooks: the idea that their works were “derivative,” belated imitations of Picasso, Klee and other Western modernists. (It’s an animosity shared by Western snobs and by Indian nationalist conservatives, who are quick to label the progressives and painters like them as rootless sellouts.)

First, such dismissals erase the considerable debt Western modernism owes to African and Oceanic art, as well as the critical influence of Hindu and Buddhist spirituality on the postwar American avant-garde. Second, they ignore how the progressives quite intentionally drew from Western examples while also looking at Asian ones, and went out of their way to fuse these diverse traditions into a politically engaged, passionately secular new art.

This show therefore includes older works of Asian art, like a pair of Tang dynasty terra-cotta horses and a 10th-century sandstone sculpture of a Rajasthani dancer, to emphasize the cross-cultural sources of the progressives’ artistic revolution. A 1962 abstraction of silver and blue murmurs by Gaitonde, who is equated with Mark Rothko in some lazy Western formulations, hangs here next to a 16th-century Japanese scroll painting of a bird on a snowy branch — and, indeed, this Indian painter had copies of similar Zen works in his Mumbai studio. Mehta learned from Picasso and Barnett Newman when he painted simplified, stylized lovers whose bodies were slashed by bold diagonals; he drew just as much inspiration from Rajasthani miniatures, like the 16th-century example here whose depiction of Krishna at war also makes use of flattened figures in solid color.

For these artists, then, Western art was not a paragon to be imitated, but one practice equal to many they could draw on in the creation of a new Indian vocabulary. And to leverage European and American examples involved no colonial inferiority complex, for, as the British-Jamaican cultural theorist Stuart Hall once wrote, “The promise of decolonization fired their ambition, their sense of themselves as already ‘modern persons.’” This cosmopolitanism became a liability in later years, especially for Husain, a Muslim, whose shows were vandalized more than once by Hindu nationalists; he left the country, became a Qatari citizen and died in London in 2011.

This show’s curators are Zehra Jumabhoy, a professor at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, and Boon Hui Tan, the director of Asia Society’s museum. They have also edited a strong catalog, whose contributors wrestle on a global scale with the tensions between art and nationhood, the promise and disappointments of secularism, and the seductive fiction of cultural “authenticity.”

Their focus on the progressives’ political orientation and on the question of whether art can, or should, embody a group identity, makes this show particularly relevant for contemporary artistic disputes, and not just in the United States. As Jumabhoy writes in the catalog, the election of the right-wing nationalist Narendra Modi as India’s prime minister in 2014 has revived the ugliest rabble-rousing over art and religion, often ending in violence.

We could all learn from the progressives’ efforts to conceive of a pluralistic Indian art, and their rejection of any “pure” essence of a culture, a race, a religion, a nation. Their new language was to be articulated out of the past, defining a future with room for everyone.

Event Information

‘The Progressive Revolution: Modern Art for a New India’

Through Jan. 20 at Asia Society; 212-288-6400, asiasociety.org.

© 2018 New York Times News Service

You must be logged in to post a comment Login