Arts

Experiments With Gandhi

| Toward the end of his life, Mahatma Gandhi, who had taken a public vow of celibacy at age 37, undertook what he described as his “last yajna (ritual)” to test his sexual impulses by sleeping naked with young women in his ashram, including his 19-year-old grandniece Manu Gandhi and Abha Gandhi, the 16-year-old wife of his grandnephew Kanu Gandhi. He acknowledged “that this experiment is very dangerous indeed,” but insisted “that it was capable of yielding great results.”

He was unpersuaded by the criticisms of such theological contemporaries as Swami Anand and Kedar Nath Kulkarni, asserting: “You have all been brought up in the orthodox tradition. According to my definition, you cannot be regarded as true brahmacharis…. I claim that I represent true brahmacharya, better than any of you. You do not seem to regard a lapse in respect of truth, nonviolence, nonstealing, etc., to be so serious a matter. But a fancied breach in respect of brahmacharya, i.e, relation between man and woman, upsets you completely. I regard this conception of brahmacharya as narrow, hidebound and retrograde.” Having resisted and conquered his carnal impulses by living a celibate life for four decades, in 1946 Gandhi was determined to test the outer boundaries of both his public and private life, indifferent to the angst it generated among his religious and political followers. “To avoid the contact of a woman, or to run away from it out of fear, I regard as unbecoming of an aspirant after true brahmacharya. I have never tried to cultivate or seek sex contact for carnal satisfaction,” he retorted to critics. He defined a true brahmachari as: “One who never has any lustful intention, who, by constant attendance upon God, has become proof against conscious or unconscious emissions, who is capable of lying naked with naked women, however beautiful, without being in any manner whatsoever sexually excited … who is making daily and steady progress towards God and whose every act is done in pursuance of that end and no other.”

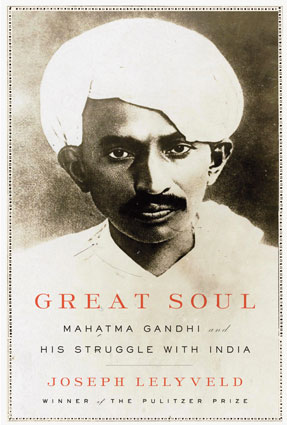

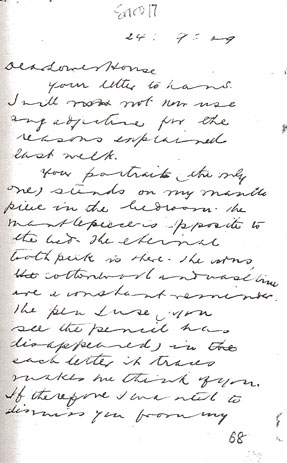

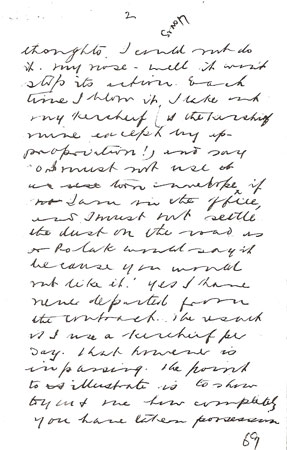

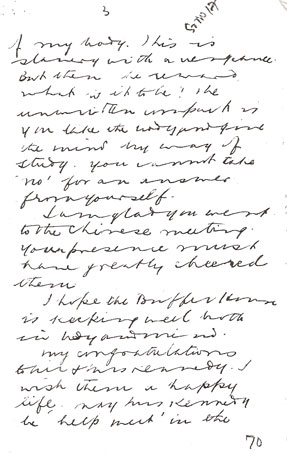

Not surprisingly, his controversial experiments drew sharp rebuke from several of his closest associates and some even left his ashram in protest, but Gandhi was undeterred, writing to one of his “dearest and earliest comrades” J.B. Kriplani, with whose wife Sucheta he had also shared his bed: “The whole world may forsake me, but I dare not leave what I hold is the truth for me. It may be a delusion and a snare. If so, I must realize it myself. I have risked perdition before now. Let this be the reality if it has to be.” By comparison, the controversy that erupted recently following media reports that a new book by Joseph Lelyveld, titled Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India, portrayed Gandhi as a homosexual, is relatively tame. Any suggestion that Gandhi might have had homoerotic attraction to a German Jew Hermann Kallenbach, among his earliest disciples in South Africa, is scarcely sensational compared to charges of pedophilia that were leveled against Gandhi in earlier books and even during his lifetime. In truth, the book neither insinuates nor implies that Gandhi and Kallenbach had a homosexual relationship. On quite the contrary, it specifically rebuts such a reading of the relationship and suggests it was platonic, something that Lelyveld was at pains to underscore in an interview with Little India. In his six-page discussion of their friendship, which Lelyveld describes as “the most intimate, also ambiguous, relationship of his lifetime,” he references a statement attributed to James D Hunt that the relationship was “clearly homoerotic while not homosexual.” He adds, “If not infatuated, Gandhi was clearly drawn to the architect.” Lelyveld’s exploration of the physical relationship between the two men centers around a letter to Kallenbach from London on Sept. 24, 1909, in which Gandhi wrote: “Your portrait (the only one) stands on my mantelpiece in the bedroom. The mantelpiece is opposite to the bed. The eternal toothpick is there. The corns(?), cottonwool and vaseline are a constant reminder.”

Lelyveld writes: “The point, he (Gandhi) goes on, ‘is to show to you and to me how completely you have taken possession of my body. This is slavery with a vengeance.’” In his interview with Little India, Lelyveld denounced the “irresponsible trashing” of Gandhi by the Wall Street Journal reviewer Andrew Roberts, who painted Gandhi as “a sexual weirdo, a political incompetent, and a fanatical faddist,” and London’s Daily Mail whose cover story titled “Gandhi Left His Wife To Live With A Male Lover, New Book Claims,” which, Lelyveld complained, “brought it down to the gutter.” The two articles lit the spark for the media frenzy that followed, prompting the Gujarat government to ban the book in Gandhi’s home state. A search on Google for “Gandhi gay” throws up 6.4 million web links; “Gandhi gay lover” offers up 1.36 million links. By contrast, “Gandhi non violence” and “Gandhi satyagraha,” for which he became internationally renowned, led to just 737,000 and 255,000 links respectively. While Lelyveld, a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist and former executive editor of the New York Times, handled the Gandhi-Kallenbach relationship sensitively in his book, bending over backwards to offer more innocent explanations (which some reviewers felt strained credulity), his research and reporting on the subject is skimpy and the casual, shallow and ambiguous treatment likely contributed to the exaggerated and false stories it spawned. In the book he admonishes readers: “In an age when the concept of Platonic love gains little credence, selectively chosen details of the relationship and quotations from letters can easily be arranged to suggest a conclusion.” But he then proceeds to undertake selective quotes from the letters himself: “What are we to make of the word ‘possession’ or the reference to petroleum jelly, then as now a salve with many commonplace uses? The most plausible guesses are that the Vaseline in the London hotel room may have to do with enemas, to which he regularly resorted, or may in some other way foreshadow the geriatric Gandhi’s enthusiasm for massage, which would become a widely known part of the daily routine in his Indian ashrams, arousing gossip that has never died down, once it became clear that he mostly relied on the woman in his entourage for its administration.”

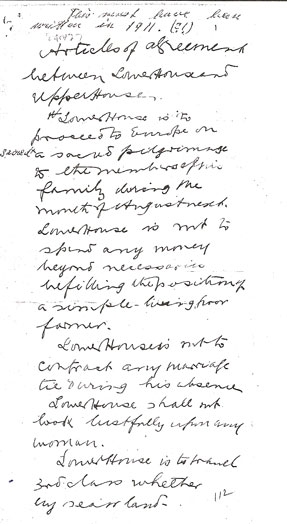

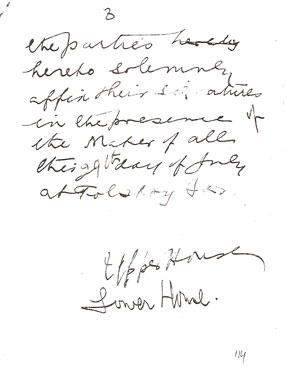

He reports, “The conclusions passed on by word of mouth in South Africa’s small Indian community were sometimes less nuanced. It was no secret then, or later, that Gandhi, leaving his wife behind, had gone to live with a man.” He then proceeds to deconstruct the “playful undertone that might easily be ascribed to a lover” in what he describes as a “mock-serious agreement” in 1911 in which Gandhi makes Kallenbach pledge “not to contract any marriage tie during his absence” nor “look lustfully upon any woman,” pledging “more love, and yet more love … such love as they hope the world has not yet seen.” At this point, Lelyveld steps back and proposes, “We can indulge in speculation, or look more closely at what the two men actually say about their mutual efforts to repress sexual urges in this period.” He points out that Gandhi’s influence on Kallenbach was so great that one year earlier, in 1908, he wrote to his brother Simon Kallaenbach in Germany, “For the last two years I have given up meat eating; for the last year I also did not touch fish any more and for the last 18 months, I have given up my sex life.” Gandhi was celibate three years before he met Kallenbach in 1904 and in 1906 took a public vow of celibacy, which he frequently discussed at his communal farms and in his writings, disclosing perceived failures when he experienced arousal or “involuntary discharges.” If Gandhi had any sexual relationship or experienced homoerotic attraction toward Kallenbach there is little doubt he would have publicly addressed the subject. He discusses far more embarrassing details about his sex life in his autobiography My Experiments With Truth, such as, for instance, his shame at the carnal lust for his wife when his father lay dying. Even Jad Adams, whose unflattering 2010 book Gandhi — Naked Ambitions, dredged through Gandhi’s “bizarre sexual history,” and even expressed “suspicion of a homo-erotic attachment on the part of Kallenbach, who was two years younger than Gandhi and never married,” dismisses any homosexual or homoerotic undertones on Gandhi’s side: “If Gandhi committed acts of homosexuality, there would be ample evidence, either justifying them or expressing shame for them,” he said.

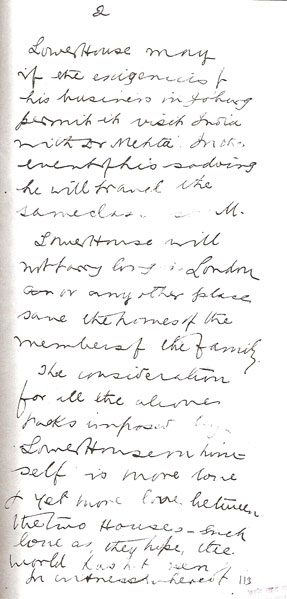

It is implausible that Gandhi, who at the time he wrote the 1909 letter, was prodding Kallenbach into celibacy and who rebuked residents of his communes for excessive tickling, would use references that might potentially inflame any passions in his disciple, which Lelyveld readily conceded to Little India (See interview). In a 1911 letter to Kallenbach, Gandhi wrote, “I have, I think, often told you that no man may be called good before his death. Departure by a hair’s breadth from the straight and narrow path may undo the whole of his past. We have no guide that a man whom we consider to be good is really good except after he is dead.” Lelyveld admits, “You can accuse me of having it both ways. I build a case and step away from it.” In fact, one can undertake entirely innocent readings of the letter, which has thus far not been published in its entirety by any media outlet, but was carried in Volume 96 of the Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (CWMG). Little India acquired a copy of the original letter handwritten by Gandhi from the National Archives of India and is reproducing it here. Lelyveld said he had not examined the original letter, but had read it in the Collected Works. The letter makes reference to what was transcribed as “corns” by the editors of the CWMG immediately before the words vaseline and cottonwool, although the word is difficult to decipher and might well be read as urns. Lelyveld said he has no idea what corns or urns might allude to and he did not include the word in the extract he excerpted in his book, even though he expressed equal befuddlement at the words vaseline and cottonwool that followed. Nor did he include the several sentences Gandhi devoted in the letter to discussing what appears to be his promise to Kallenbach not to use torn envelopes to blow his nose, but to use a “kerchief” instead, which precede the reference to Kallenbach having “taken possession” of his body.

Little India also dug up several letters by Gandhi in which he recommends the use of vaseline for various medical treatments. In a December 1928 letter to Chhaganlal Joshi, for instance, he advises, “Gangabehn should put her feet in hot water with soda bicarb mixed in it and massage them long with vaseline before going to sleep.” In another April 1933 letter to Narandas Gandhi, he writes: “Vaseline will help Amina better than ghee can. She should thoroughly mix a little boric acid powder with it.” Lelyveld said he had been contacted by a Gandhi scholar who had pointed out that Gandhi shaved with vaseline and after researching the use of vaseline for such purposes on the Web, “I actually will make a change in the later edition” of the book, currently in its third printing, to indicate such a possibility as well. Lelyveld said he did not anticipate that his discussion on the relationship between Kallenbach and Gandhi would attract such attention as it “does not seem to me news or a great revelation. It’s been discussed a lot more loosely in various places than it was by me.” People thought “that I was insinuating that Gandhi was gay, but that was not on my mind,” Lelyveld said. “I am interested in Kallenbach for other reasons.”

Lelyveld’s reporting is equally wanting in other sections of the book, some of which have not attracted media attention. At the end of the book, for example, he discusses Gandhi’s assassination, during which Gandhi is widely believed to have uttered the words “Hey Ram,” which Lelyveld mocks as the popular “hagiographic note” on which most biographers bookend Gandhi’s life. He points out that “Gandhi anticipates his impending death so many times in his final days that he almost seems party to the conspiracy,” bringing up the subject 14 times over 10 days. Gandhi repeatedly expresses the hope that if he were killed he would die with Rama’s name on his lips. The day before his assassination, Lelyveld writes, “[H]e again tells (his niece) Manu: ‘If an explosion took place, as it did last week, or someone shot at me and I received his bullet on my bare chest, without a sigh and with Rama’s name on my lips, only then you should say that I was a true Mahatma.’” Lelyveld questions the testimony provided by Manu, who was physically closest to Gandhi and was knocked down by the assassin Nathuram Godse: “[S]he hears what for weeks she’d been trained to expect: ‘Hei Ra…ma! Hei Ra…” She writes, ‘The sound of bullets had deafened my ears,’ but also says that she distinctly heard the prayer that Gandhi said could validate his mahatmaship.”

Noting that “the killer Godse and Vishnu Karkare, one of his cohorts stationed nearby, testified that all they heard from the victim was a cry of pain, something like ‘Aaah!’” Lelyveld wonders: “Whether a seventy-eight-year-old man who had taken two slugs fired at point-blank range in the abdomen and one in the chest could conceivably have uttered four or five prayerful syllables as he fell is a forensic question not easily answered at a distance of more than six decades. If he could, it might qualify as something of a miracle, of a sort not infrequently ascribed to saints.” Lelyveld is justified in being skeptical, as, he points out, some Hindu nationalists were, of the popular “belief that [Gandhi] fulfilled his ambition of dying with the name of God on his lips.” In fact, the subject has been the subject of media and scholarly scrutiny as well, such as in the paper “Hey Ram: The Politics of Gandhi’s Last Words” by Delhi University and University of California at Los Angeles Professor Vinay Lal in the January 2001 issue of Humanscape. But Lelyveld himself demonstrates little inclination to investigate the issue in any depth, explore new evidence or shed any fresh light on the subject. He seems content to plough the ground just enough by juxtaposing the competing versions of Gandhi’s closest aides against those of his killer, so it fits his narrative on Gandhi’s ambiguous legacy. He told Little India, “I am satisfied to be agnostic on that question…. I don’t know who I could interview and what I could read that I have not read that would clarify. In some ways I think that the mystery of that instant should be allowed to remain a mystery….”

Lelyveld’s journalistic shortcomings in these key areas (which unfortunately ended being trivialized and sensationalized) notwithstanding, his book is a valuable addition to the voluminous literature on one of the most iconic figures of the 20th century. He brings Gandhi’s South African experience and how it shaped his evolution as the preeminent leader of India’s independence movement into focus as well as his quests as a “social reformer, with an evolving sense of his constituency and social vision, a narrative that’s usually subordinated to that of the struggle for independence.” In fact, Lelyveld vividly demonstrates, toward the end of his life, Gandhi’s overweening emphasis on social reform and his personal and spiritual pursuits caused him to subordinate (and at times compromise) the Independence struggle. Lelyveld writes: “I’m more fascinated by the man himself, the long arc of his strenuous life, than by anything that can be distilled as doctrine.” Unfortunately, these fascinating explorations have now been obscured by the Gujarat government’s censorship of the book, the controversy over Gandhi’s sex life and what one reviewer denounced as Gandhi’s “implacably racist” attitudes toward Africans (a subject Little India will explore in the next issue). Ironically, Gandhi might have delighted in the public curiosity over his sexual life from a century ago. He was undeterred by the discomfort his sexual practices and pronouncements created among his closest disciples, including his political heir and the first Prime Minister of independent India, Jawaharlal Nehru, who found them “abnormal and unnatural.” Gandhi was so obsessed over his chasteness throughout his life that he frequently tested his resolve and repeatedly chastised himself publicly when he was unable to meet his lofty ambitions. In 1936 he wrote: “I have always had the shedding of semen in dreams. In South Africa the interval between two ejaculations may have been in years. Here the difference is in months. I have mentioned these ejaculations in a couple of my articles.”

Sudhir Kakar, a psychoanalyst, who has explored and written extensively on Gandhi’s sexuality, has written: “We can … never know whether Gandhi was a man with a gigantic erotic temperament or merely the possessor of an overweening conscience that magnified each departure from an unattainable ideal of purity as a momentous lapse.” In any event, Kakar concluded: “The only way Gandhi could ever lose the high regard, even reverence, in which he is held all over the world would not be because of the discovery of any byways of his sexuality, but if it was found that he had lied about them or, by Gandhi’s own high standards, that he had not told the truth loudly enough. Such a discovery would strike at the heart of what made him a Mahatma: his uncompromising integrity.” Whatever else we may know or not know about Gandhi, of this we can be sure: He most surely would not have discouraged debate or criticism of any aspect of his fascinatingly complex life. On quite the contrary, he would have actively encouraged and engaged it. Lelyveld points out in his book how Gandhi rebuked his interpreter Nirmal Kumar Bose for “glossing over in his Bengali interpretation his attempt at one of his prayer meetings to offer a frank public account” of his controversial practice of sleeping with naked young women toward the end of his life. Even more remarkably, when his stenographer Parsuram quit over the sexual experiments, expressing concern that the resulting gossip would undermine his public image and social objectives, Gandhi wrote, “I like your frankness and boldness…. You are at liberty to publish whatever wrong you have noticed in me and my surroundings. Needless to say you can take whatever money you need to cover your expenses.” Those words alone are eloquent testimony to Gandhi’s genius — and greatness.

|

You must be logged in to post a comment Login