Arts

Everyone's A star

Just about everyone is jumping into the movie business these days. The monsoons may be hitting Mumbai, but in America it's raining desi filmmakers, producers, directors and actors!

|

It seems computer programmers, physicians, financial consultants, students, engineers, fast food cooks – just about everyone, we mean everyone – wants to be a star! And slowly but surely they are emerging from the highways and the byways, and every possible profession, to claim their 15 minutes of fame.

Take California-based Jaya Jayaraja; you could spin a Bollywood film out of his life story! A descendent of Tamil rubber tappers in Malaysia, Jayaraja slogged as a cook at a Kentucky Fried Chicken outlet in Singapore even as he nurtured his dream on the rotesserie to make films. After all, he had grown up watching all kinds of films from Indian masala fare to the local Malaysian and Hong Kong Chinese films as well as Hollywood cinema. He picked up cinema by watching it in darkened theaters, even as he cooked chicken in the night shift for three years and saved his money. He came to California hardly knowing a soul and worked at every job imaginable from janitor to a roady in a car show. Over the years he worked in nine different restaurants, all the while attending community college at night, learning film production. When he was studying film at the University of California Los Angeles over weekends while holding a fast food job, one of his instructors seeing just how hungry he was for cinema helped him land a job as production assistant for Rising Sun, which starred Sean Connery. “It was my first exposure to what goes on in a film set,” he recalls. “There were 80-90 crew members and I was wondering what do they all do? I kept watching the director and asking questions. You’d be surprised, the bigger they are, the more humble they become; they just don’t mind talking to you. In my experience, it’s the up and coming ones that don’t have time for you. The bigger they are, they love to talk to you!”

One of the directors had someone teach Jayaraja the rudiments of camera work. He spent six months doing that, after which he joined the union and started saving money to make his own film. He says, “Every day I come to work – I’m a sound guy and making pretty good money – but I’m not happy. It took me ten years to save 25 grand to make my first movie.” Such are the struggles Indian Americans go through to fulfill their cinematic dreams. Nowadays, there are just so many young filmmakers, writers and actors on both coasts that you can hardly keep the names straight. Filmmakers are popping up just about everywhere, be it Chicago or North Carolina or Texas. From full time professionals to weekend freelancers they are all looking to gain attention on the festival circuit and, if their luck holds, land a distributor. While many of the filmmakers went to film school, several others are in other careers and are pursuing films on a part-time basis, shooting on weekends. Yes, everyone wants to be in the movies, in front or behind the camera! They come from different backgrounds, different lifestyles and so surely the films they make run the full gamut. At the recent IAAC Festival of The Indian Diaspora in New York you could see the wide arc of Indian American films, both in quality and subject matter. Aroon Shivdasani, director of the non-profit Indo-American Arts Council, started the festival three years ago with just 25 entries. This year she received 60 films and a lot more audience participation, with some screenings sold out.

“The independent filmmaker has matured,” she says. “People at one stage expected them only to talk about ABCDs and FOBs, but they’ve gone beyond that. They are now comfortable in their own skins and are able to explore a little further and talk not only about the new immigrant in America and their own lives; they are also able to tell stories just about people here.” Says filmmaker Mira Nair. “Someone was asking me what are the attributes that define independent film making and I said for a person to be an independent filmmaker you have to have bravery, loneliness and stamina. And I really want to celebrate the bravery, the loneliness, and the stamina that all the directors have had with their films.” Nair admits that times and attitudes have changed since she first started making films: “It’s such a different time now. I never thought I’d ever sound like a dadi maa but it’s been about 25 years since I left college and that’s when I started making films and I remember to this moment the acute loneliness of getting on the Greyhound bus after finishing a film and taking a print of it under my arm and going around this country for six weeks, showing it anywhere anybody who would want to see So Far From India or India Cabaret or any of my documentaries and feeling incredibly – actually idiotic – when I was faced with audiences who would say to me ‘I saw running water in your movie; do you have running water in India?’ “And I would just wonder, ‘Who am I making my films for?’ and it was an acutely lonely moment and really reminded me of the disease, the affliction we have to feel to continue to be independent film-makers.” The many aspiring filmmakers and actors at the IAAC festival seemed to lap this up, coming as it did from Nair, whose very first feature film Salaam Bombay! was nominated for an Oscar and whose latest Monsoon Wedding was a runaway success. Nair recently directed the Thackeray classic Vanity Fair starring Reese Witherspoon and her upcoming projects include Tony Kushner’s Homebody/Kabul for HBO and Hari Kunzru’s The Impressionist.

Indeed, aspiring film-makers here have so many inspirational fairy tales with happy endings: the story of Ismail Merchant, a boy from Mumbai who created a splash in Hollywood, with the award-winning Merchant-Ivory films, which are now an American legend; Shekhar Kapur, the Bandit Queen film-maker who brought the color and chutzpah of Bollywood to his production of Elizabeth; M.Night Shyamalan, a 21-year-old who almost became a doctor, turned to films instead and knocked Hollywood’s socks off with The Sixth Sense and Signs, making millions for the studios and himself; Gurinder Chadha’s Bend it Like Beckham raked in millions this year and opened the door for ethnic films. Deepa Mehta, whose films Fire and Earth prove there are always audiences for powerful human stories. For apprehensive parents, all these success stories wrapped in dollar signs have given filmmaking not only respect as a career, but also reinforced the cachet it always had from their days in India. After all, who can quarrel with fame, fortune and celebrity?

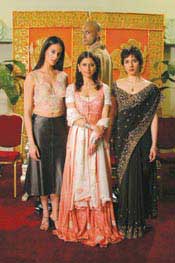

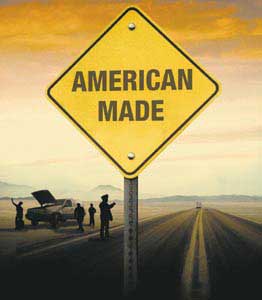

Many second generation Indian Americans are planning careers in cinema and acquiring the skills to create powerful films. They are getting initiated into the business with short films produced in school, films which pack a real punch into a brief time frame: Sharat Raju, director of American Made, has a MFA from the American Film Institute in Los Angeles and received the Richard P.Rogers Award for Excellence in directing; Sabrina Dhawan, who graduated from Columbia University’s film program made the powerful Saanjh as her thesis film and this has won several awards and has toured 20 festivals; Abhay Chopra, who is currently enrolled at the Undergraduate Film and Video Program at the School of Visual Arts, has made Reflections. Keshni Kashyap, director of Hole, currently studying MFA in Film from UCLA, received the prestigious Spotlight Award of the Festival of UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television; Amisha Upadhyaya, who trained in theater at Columbia University and the Lee Strasberg Theater Institute, directed Imperfection. The strong themes and sure directorial hand in these short films makes one look forward to larger ventures from these aspiring filmmakers.

Apart from these students of cinema, there is another category of Indian American filmmakers who have already established their name, such as Nagesh Kukunoor, who gave up a lucrative career as an environmental consultant in Atlanta to make films. His first film Hyderabad Blues, in which he also acted, was written, produced, directed and financed by himself and went on to become the largest grossing low-budget Indian film in English. It ran to packed houses across India and also won the audience awards at the Peachtree International Film Festival in Atlanta and the Rhode Island Film Festival. Kukunoor’s other films Rockford and Bollywood Calling also did well. His latest Teen Deewarein is an offbeat prison tale that has generated a lot of buzz in India. Kukunoor has also started a distribution company to promote the work of independent filmmakers. Then there’s Tanuja Chandra, who graduated in film direction and writing from Temple University, Penn., and has moved solidly into Bollywood with films like Dushman and Yeh Zindagi Ka Safar, and has also scripted films like Tamana, which won a National Award, and the highly popular Dil To Pagal Hai for Yash Raj Productions. She recently directed the Lucky Ali starrer, Sur. Chandra moves easily between two worlds: she lives part of the year in Philadelphia and her next film Hope and a Little Sugar, about 9/11, is being shot in New York.

These filmmakers, wading deeper into ever-widening worlds, find all subject matter open to them, be it Home or the World. Satish Menon, a filmmaker based in Chicago, had no qualms about shooting his debut film Bhavum entirely in Kerala in Malayalam, with English subtitles. Perhaps one of the most assured new voices amongst emerging Indian American filmmakers is that of Nisha Ganatra, who was born in Vancouver, Canada, and studied filmmaking at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University. She has been fully baptized in the film industry waters, having been camera assistant, cinematographer, production supervisor, actor, director and writer. Her first feature film Chutney Popcorn took tired clichés of desi immigrant life and turned them on their heads. The film won several awards at international film festivals. Her new film Cosmopolitan is adapted from a short story by Akhil Sharma in The New Yorker and the screenplay is written by another young Indian American, Sabrina Dhawan, who earlier wrote the screenplay for Monsoon Wedding. The film is produced by Gigantic Pictures as part of hour-long literary adaptations for Public Broadcasting Services, and was funded by Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the National Asian American Telecommunications Association.

Indeed, making a film is only half the battle. Finding funding for marketing and eventually bagging a distributor are the other travails awaiting neophyte filmmakers and their films, which range from ABCD dilemmas to tales of life in America. Nair, who reminisced about her trials to the emerging filmmakers, said, “But time has galloped on in the 25 years since I began, and now it’s a completely different moment. We have these amazing festivals of the Diaspora, we have homes to come to with our work, and we have audiences that wait for it. It is the culture now that hybridity is celebrated …and we have places to go.” The places are certainly there: from Diaspora film festivals on both coasts to screenings of Indian cinema in mainstream museums. Fortunately, this explosion of Indian American films has dovetailed with the increasing fashionability of Bollywood in American eyes. Bollywood is cool, and museums are showing not only masala fare, but also the art house and offbeat films which rarely get a showing.

Most of these movies don’t turn their producers into overnight millionaires. In fact, American Desi, made by the brothers Gitesh and Piyush Pandya, was one of the rare movies, which, produced on just $200,000, grossed over $2 million from the U.S., UK and Indian markets. Meanwhile Piyush is currently developing his second directorial venture titled Arranged Marriage, a comedy shooting next year. Gitesh, who also heads Boxoffice Guru.com and is currently programming the Bollywood Shuffle festival at BAM, notes, “Locally made Indian American films have had mixed results at the box office and generally have had trouble reaching $150,000 in North America. DVD revenue can sometimes be better. Bollywood films still get plenty of marketing support and wider distribution, but the hits are few and far between this year.” He does believe that things have become easier in the past few years, both in finding investors and interest in the mainstream: “Many filmmakers have been able to get funding for projects. However it is getting more complex to capture the audience’s interest, because there have been so many NRI films with similar stories coming out. I think the best films with the most entertainment value will stand out, regardless of whether they are Hindi-language Bollywood films or English-language films made in the U.S and UK.”

With so many techies awashed on U.S. shores, it is inevitable that a circuitous route would send a few into cinema. Manish Gupta, the director of Indian Fish in American Waters came to the United States in 1998 from Indore to work in the software industry. Asked about the financing for the film, He says, “In this economy it’s really tough to raise money. After American Desi I’ve not really seen any other movie making back its money. Because of piracy, the market is in very bad shape. Anybody who’s going to invest is going to look for a return on investment.”

Gupta and four friends, all from the IT industry, financed the film. He says, “They also helped out a lot. They all enjoyed the process and very openly say that life was otherwise getting very mundane. We put in the money and really enjoyed the one year of our life that this movie was being made. Now we’re getting the recognition, so it’s looking very good.” Says Gupta, “Festivals are where all the scouts come. Luckily for us filmmakers, after Monsoon Wedding and Bend it Like Beckham, Indian movies are really hot. If there is a good product, then the market will pick it up. Mira Nair and Gurinder Chadha have really made our life very easy now.” Producing films has also become more viable, thanks to the digital revolution. American Fish was made at a cost of under $100,000 with digital technology. Says Gupta: “There’s also lots of help available. There are about 200 young Indian Americans in New York who are full-time pursuing acting or writing or filmmaking, doing odd jobs on the side. They are devoted to finding a career in film-making.” Growing up in a middle-class family in Hyderabad, Nikhil Kamkolkar remembers showing the neighborhood kids projected stills from Bollywood on a cheap tin projector purchased at a street fair. So it was inevitable that he take film classes as an undergraduate at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. His debut feature film Indian Cowboy will be completed next year. He says, “There is a movement afoot, not defined by ethnicity,ºin my opinion, but by the impact of technology on the craft of telling a story visually. I’m excited about high definition, about the impact of computer software on the craft of making an image and moving it. Both the opening and end title animations for Indian Cowboy were done using Adobe’s AfterEffects software on a PC!” Raj Nidimoru and Krishna DK, the filmmakers of Flavors, went to engineering school together in India. “Among the things we shared in common was a huge passion for the movies. So a few years after we came to the U.S. as software consultants, it was the most natural thing for us to translate that passion onto celluloid reality. Films are our school. All we talk about is films: at work, at home, on the email, over the phone, anywhere, any time. That’s all we want to do. We even plan to quit software soon!” The two took film classes to hone their skills and also assembled a cast and crew of professionals such as Frank Reynolds, editor of the Oscar nominated film In the Bedroom and Ronna Wallace, executive producer of Reservoir Dogs as consultant. The film has been shown to good reviews at film festivals like Milan, Hawaii and the Hamptons

Manan Kotohora went from an MBA and a corporate job at Nortel Network to filmmaking. He says, “I was in IT industry, and I still am. And will continue to be. Filmmaking is my passion, my hobby. I don’t earn my bread, butter or Bacardi from it.” He, however, earned a diploma in scriptwriting and got film producer Tirlok Malik involved with his first film, Arya which showed recently at the New York International Independent Film Festival in Manhattan. Kotohora also maintains a Wacky Wednesday list serv frequented by scores of aspiring filmmakers and actors. Amin J. Rupani is a successful engineer/entrepreneur smitten by the film bug. The owner of a circuit board design engineering company in Elk Grove Village, Ill., he recently directed and co-produced with Yunush Ajmeri a romantic comedy titled Legally Desi. As a child, he was fascinated with the world of make-believe on the set of a TV serial in Karachi, Pakistan, and so it was no surprise that he studied film as a minor in college in Silicon Valley. The partners are now planning to take Legally Desi on the festival circuit. Vikram Yashpal is another filmmaker, who is an engineer by profession and has worked in a hi-tech company. He has also been acting in theater for over a dozen years. Along with a group of computer specialist friends, he founded Katha Films to produce immigrant relevant films and Trade Offs is the debut venture of the company. Ask him how he financed the movie, and he grins wryly: “Friends, family and fools helped us in making our dream movie.”

Finding fools – or visionaries – is perhaps the most difficult, but sometimes things just fall into place. Babar Ahmed, who studied filmmaking at New York University’s Film School, pitched the script of Genius to Dr. Ali Javed, who is president of a successful private biotech company in the U.S. and secured solid backing. The film acquired nationwide mainstream video distribution. It is a film without a single South Asian in it and tells a very universal tale. Some IT professionals are not just making films, they getting into their financing. Did it have something to do with the bursting of the dotcom bubble? Did life after the bust turn out to be stranger than fiction? Ask Vivek Wadhwa, founder of Relativity Technologies: “If you had spoken to me a year ago and asked what projects I saw myself getting involved with, I would never have dreamed of Hollywood or Bollywood or anything outside technology for that matter.”

Says Wadhwa, “Brad is an ex-investment banker and I have run pretty large operations. This movie is being run like a startup technology company, with the highest levels of professionalism and accounting.” The duo have raised capital from some major players in the IT industry, such as telecom executive Ashok Rao and Swadesh Chatterjee, who is the current president of TiE Carolinas, as well as some physicians. While this film is being shot in India with Hollywood actors, Lal and Kishore Dadlaney of Video Sounds are producing a movie shot solely in the United States with Bollywood stars. About two years ago they produced Kehta Hai Dil Bar Bar entirely in New York and New Jersey, starring Bollywood actors Jimmy Shergil, Kim Sharma and Paresh Rawal. Their new venture, Hope and a Little Sugar is being directed by Tanuja Chandra and stars a Bollywood cast, but is being shot entirely in New York. Dadlaney believes there’s definitely a movement afoot: “We are heading out for more and more Indian Americans selling movies to India, making movies here, very cost-effective movies, and different subjects rather than just the Bollywood style subjects which keep coming from India. So there’ s a lot of back and forth going on. I feel the globalization has really come into the Indian trade.

“My personal view is that first it’s the curry that invades other nations, then comes the henna and yoga and the bindi stuff and then Bollywood crosses over. I think we are poised for crossover. It has sparked a talent revolution that is very important. There will be disasters along the way, but it’s good experience for young Indian Americans are coming up with good new subjects rather than the simple song and dance that comes out of India.” And what’s their new song and dance? Rohit Karn Batra, who grew up in the Bible belt of the Carolinas, is a self-taught filmmaker who has just completed a short film, Alchera, in 16 mm and is collaborating with Gotham Chopra, Deepak Chopra’s son, on some short films. He believes Indian American film-makers have a long way to go and are learning by a process of trial and error: “Personally, I’m going to bang my head against the wall if I see another ‘Hey, I’m so confused about my culture … it’s funny … am I Indian or am I American?’ film. I want to be entertained like anyone, but I also want substance.” Nisha Ganatra finds far too many filmmakers willing to exoticize their own culture to fit the needs of the mainstream audience. She asks, “Actors sometimes don’t have a choice, but when you’re the filmmaker and you’re writing and creating the film, why feed the exoticizing machine, why not create subversive images or tell stories within that expectation and turn them on their head or do something a little more long-lasting?” She adds, “We have this rich history, what India has accomplished, Satyajit Ray has accomplished, Mira Nair and the movies like My Beautiful Launderette from London. It seems like the American scene has moved backwards. “We should take all those works that were ground-breaking and try to push the envelope further.” It’s with just such a goal in mind that Mira Nair’s Mirabai Films is starting a non-profit filmmaking lab next summer. Called Maisha, a Swahili word meaning life, it will bring together a dozen young filmmakers for three weeks each year in East Africa, Nair says, “to help people to tell stories, really create filmmakers.” “It’s not enough for us to be expressing ourselves,” says Mira Nair. “We have to make cinema which is excellent and painstaking and not just casual and just fun, and make it commensurate with standards of excellence and not weep and apologize for being from the third world anymore… Let’s bring to the world a cinema that reveals all our worlds in its multiplicity, in its strength and in its passion.” |

You must be logged in to post a comment Login