Life

Calligraphy in India

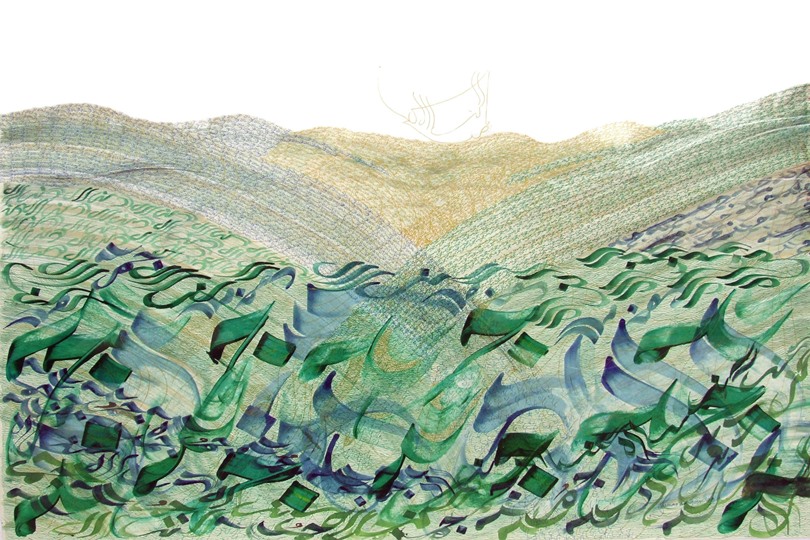

Ganga Jamuna (The Confluence), Qamar Dagar, exhibited at the India International Centre, New Delhi.

Calligraphy has moved across paper, coins, seals, metal objects, copper plates, arms and armors, etc., wherein it also blended with flora and fauna designs.

The aesthetic art of writing frolicks into art forms that harp more on the visual than the semantic. Zoomorphic calligraphy, outlined by animal figures, was in vogue in the Deccan as early as the 16th century. Its present passage is much more besotted with abstraction, a blend of Arabian calligraphy with abstract art.

One calligraphic stroke is one life. It goes from opaque to the transparent. How long it sustains the ink? How long does it remain legible? Qamar Dagar, a well-known Delhi-based pictorial calligrapher, is prodded by these thoughts, “Appearance of design from distance, but closer look will reveal letter.”

Al Wasio (The All Embracing) by Qamar DagarIt took nearly 4,500 years for phonic utterances to get transcribed into a script. Over time, several scripts and different languages adopted adornments on their scripts. The art of calligraphy reflects the aesthetics of the then and now society. The epigraphs bear testimony to the changing paradigm of the art of writing.

Calligraphy has moved across paper, coins, seals, metal objects, copper plates, arms and armors, etc., wherein it also blended with flora and fauna designs. Artifacts used to be decorated with different techniques, such as koftgari (damascening), bidri or niello (inlay in metal), engraving, writing, printing and embroidery on textiles, etc.

The National Museum, New Delhi, houses many artifacts and textiles in its collections bearing calligraphy. Dr Anamika Pathak, the curator with the Decorative Arts Gallery, points out: “Several talismanic garments, like choga or tunic bear Naskh (an Arabic style) calligraphy. Several textile pieces like thalposh (coverlet), circular table cloth, rectangular datarkhan and parde or spreads have qasida (Persian couplet) and sufiana halaram (mystic verse) written in calligraphic mode. Masulipatanam (Andhra Pradesh) was a thriving center for the Iranian market.’

Forty years ago, Anis Siddiqui (see sidebar) revived Indian calligraphy from the throes of stagnation and popularized it through workshops in different Indian languages. Early on, his strident strokes were austere, shorn of embellishments. But now he often invokes pictorial depictions and spectral strokes. Calligraphers are even taking on different mediums, such as mica or wood. The gold filigree and gem inlay of Islamic calligraphy may have faded into oblivion, but more subtle art is debuting in its place.

Qamar DagarIrshad Hussain Farooqi practices several styles of Arabic calligraphy, such as Thuluth, Kufi and Diwan, on wood, among very few Islamic calligraphers practicing on wood in India. He has made unique calligraphic designs of several surrahs (chapters) of The Holy Quran.

He says: “General calligraphy is two dimensional however in wood presentation I make it three-dimensional. Tughras that are traditional designs made on paper cannot be replicated on wood, but have to be carved out. This is a highly intricate affair.”

He has produced several calligraphic works. “The very first design that I modeled out of my hands was the name of Allah in the shape of a surahi, a water urn that I expanded into more complicated and complex designs. Besides I’ve designed Al Faatihah, the opening chapter of the Holy Quran. The outer big circle has 114 beats denoting the 114 surahs, that is chapters. And the inner smaller circle has 52 beats denoting the number of weeks in a year.”

Irshad Hussain was captivated in his childhood by Mastan Baba, a wandering Sufi from Bangalore, who is revered as an exemplary calligrapher, who often made talisman by calligraohic Bismillah’s name and was reputed to have miraculous powers. . When he grew up a chance visit to a calligraphy exhibition rekindled his childhood fascination to seriously take up calligraphy.

J.D. Chakrishar, who hails from Sikkim, is imbued with the ancient art of Tibetan writing. In 2010, he produced the world’s longest calligraphy on scroll. It took six months to write the scroll, which contains 65,000 Tibetan characters,written in different calligraphy styles, including Tsugring, Tsugthung and Tsugma Kyug forms of Umed.

Pre-Islamic period in India

The Kailashnathar temple built in the 8th century by the Pallava ruler Rajasimha in the then capital city of Kanchipuram bears inscriptions noted for exotic calligraphy. The king’s 21 titles are incised on the niches all around the enclosing wall of the temple in ornamental florid Pallava Grantha characters. The inscriptions are designed to resemble swans, peacocks, snakes and creepers. At Mahabalipuram in Tamil Nadu, the rock cut caves, monolithic free standing temples, open air bas-relief and structural temples are replete with inscriptions of the epithets of Pallava rulers. During the Chola reign, whose capital was Tanjavur, Rajaraja I built the grandiloquent Brihadeisvara temple, which bears the king’s various titles in ornate calligraphy. Both Kharosthi and Brahmi scripts, during emperor Ashoka’s, time were highly calligraphical. The Jain manuscripts of the illustrated Kalpasutra are replete with calligraphy, though very austere compared to the Persian style.

The Islamic bloom

Uday (The Rise) by Qamar DagarWhen Muslim rule was established in India in the 12th century, many forms of Islamic calligraphy were introduced to India from Arabia and Persia. But interestingly enough, India also contributed a new calligraphic style to the Islamic world during the reign of Tuglaq Sulans in Gujarat. This indigenous style was a bold variety in which round strokes left no sharp endings. The calligraphers from the court of Bengal Sultans gave a new dimension to the existing Thuluth style and created their own variety, found in the epigraphs of Bengal. The vertical strokes in this variety are arranged in a way that resembles the stems of coconut trees, a regional motif. Art historians hail it as “bow and arrow” style or moving swans or boats against a backdrop of coconut trees on the coast.

Koran manuscripts in the Bihari script were widely appreciated and exported from India to South Arabia. Just about a decade ago, torn pages of 15th century Bihari script were discovered in the ruins of a mosque or madrasa at Darawan in northern Yemen following an earthquake that had devastated the entire town. This distinctive script used exclusively in India came to be called Bihari, but the origin of the name is obscure and disputed. Bihari script came to the fore during the 15th and 16th centuries and Koran manuscripts are found in the Bijapur Archeological Museum, the Khalili Collection and the British Museum.

One of the earliest zoomorphic calligraphy in India depicts the Throne Verse of the Holy Koran in the shape of a horse. The text begins at the animal’s head. His nose and mouth form the Word Allah as though the horse were evoking the Divine name through his lips. Astride the horse is a small bearded figure surrounded by plants, all drawn in a calligraphic style typical of India in the late 16th and 17th centuries. In this manner, the word and picture bolster the divine omnipotence, realized as a mighty horse bearing a minuscule figure representing the human soul.

Opening chapter of Holy Q’uran, by

Irshad Hussain Farooqi.During the 3rd and 4th century AD the Nabatean script gave rise to the formation of Arabic script. However until the 8th century, the Arabic script had no orthographical marks. The need arose when Islamic missions started preaching Islam to non-Arabs. The people of Persia till then had not adopted Islam and wrote Persian in Pahlavi script.

What led to the evolution of Islamic calligraphy? The prohibition on depiction of human or living beings in the tenets of Islam prodded graphic artists and calligraphers to devise a trope to render beauty in the written word to adore their facades and interiors of buildings, mihrabs, portals, cover and pages of books, epitaphs, wall-hangings, etc., resulting in several distinct styles of Islamic calligraphy.

Dr Savita Kumari, an assistant professor in department of history of art, National Museum Institute, New Delhi, says: “The pre-Delhi Sultanate period from 1192 to 1316 is replete with calligraphic works on monuments like the Alahi Darwaza in Qutub Complex and Sultan Garhi. The reason was to consolidate their ideas upon a new place they had taken over. Tombs built in the later phase did not have such elaborate calligraphy. In Tughlaq monuments, we find much lesser calligraphy. Shah Jahan used calligraphy on Taj Mahal with political intent, however Akbar and Jahangir did not do so.”

The advent of paper after the 12th century likely diverted the depiction of calligraphy from monuments to manuscripts.

The distinct styles such as Khatt-i-Gulzar (rose), Khatt-i-Ghubar (rose-petal), Khatt-i-Mahi (fish), Khatt-i-Sunbuli (ear of corn), Khatt-i-Raihan (jasmine), Khatt-i-Paichan (curl) and Khatt-i-Nakhun (nail) arose in places very difficult to trace, perhaps India, Turkey or even Persia. Al-Sunbuli is a heavy and highly stylized script that was probably derived mainly from the Divani script.

The first revelation of the Holy Quoran deals with the art of writing, a gift which God bestowed on man — “Who taught by the pen.” The second Koranic revelation is entitled al-Qalam — “The Pen.” One of the many sayings on calligraphy attributed to the Prophet Muhammad is, “Good writing makes the truth stand out.” Calligraphy is Islamic sacramental art. The tradition of calligraphy continues to the present day in the cloth which covers the Ka’bah, the Sacred House of God. It is traditionally decorated with panels and bands in Jali Thuluth in gold and silver.

Zam, seed mantra for Zamphala, in contemporary calligraphy by J.D. Chakrishar.

Gulzar is the technique of filling the area within the outlines of relatively large letters with various ornamental devices, including floral designs, geometric patterns, hunting scenes, portraits, small script and other motifs. It is often used in composite calligraphy, when it is also surrounded by other decorative units and calligraphic panels.

Aynali is the art of mirror writing, in which the unit on the left reflects the unit on the right. There is a book or two written with embossed nail impressions, a method called called Khatti nakhoon. There is still a person in Amroha, near Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, who does it to this day with aplomb.

|

Keeper of the Flame Anis Siddiqui, a doyen of Urdu calligraphy, who has made immense contributions to popularizing and teaching its skills in different Indian languages, speaks to Little India.

A. Well I started teaching calligraphy in 1975 in Jhunjhunu, Rajasthan, and thereafter in Darul Ulum Deoband Islamic University, Ghalib Academy and now in Jamia Millia Islamia University. I started my exhibitions and talks in 1984. Are your calligraphy workshops across India mostly in Urdu? Calligraphy can be practised with any language. I hold calligraphy workshops in several languages, like Malayalam and Assamese, to prove the effervescence of calligraphy. I do not know Malayalam, but enjoyed making the rounding script. I have been to 21 states, 250 cities totaling 450 workshops. I’ve done it with four languages of South India, Assamese, Bengali and Punjabi. There is a lot of interest for Gurmukhi in Ludhiana and for English calligraphy in Kota, Rajasthan. Most sadly and surprisingly, Hindi calligraphy has no takers. People do not go for Hindi and Urdu workshops. In fact with the rise in computers, calligraphy has got wiped out in Urdu.Whoever practices calligraphy in Urdu can do so in Arabic, letter designs remain the same. Owing to Hindi influence, Urdu has more alphabets than Arabic. Even Sindhi is similar. Calligraphy is changing its paradigm. Even your present calligraphy has more colors and visual depiction. Those days we did not have colors in calligraphy. But now we’ve to make it decorative art and visual art. What I see around, the changes, vistaar (adaptation and extension) must be brought in our work to prevent it from coming to a standstill like what happened with Hindu and Jain works. What is the prerequisite to become a calligrapher? What are those intricate things that determine its quality? Qalam se mood ko copy karna, that is to bring out one’s feelings through strokes is what matters. The signs of calligraphy must be maintained. What is the angle of stroke in Hindi, Urdu and English? The angle that the pen makes is not known to many. During the stroke of calligraphy, the change of angle determines the course. Over these years you must have built a huge collection of your works.

More than 1,000 works in Urdu. Since 1990, I’ve done assignments for filmmaker Muzaffar Ali for his film Je Nisar that revolves on Rumi and Shirazi. I did extensive calligraphy covering three rooms, while they were shooting at Lakhimpur in U.P. Is calligraphy offered in any academic curriculum in India? In 2000, I proposed to Jamia Millia Islamia University to include calligraphy in its curriculum. Around 2008, they did so. But it happened through fine arts. I’m now teaching there. Nowhere else any academic curriculum exists in India, maybe one in Aligarh Muslim University. Isn’t calligraphy gaining in popularity? The grammar of calligraphy cannot be what logo designers do. I do not call them calligraphers. It’s not growing as an art, but pictorial depiction is happening bereft of calligraphic strokes. People do not want to learn calligraphy with rules. Even nowadays, there may be just around 25 calligraphers of merit in Delhi. In Hyderabad there are three really good ones, like Abdul Gaffar, and Nayeem. Likewise in Mumbai and Kolkata there are just two to four such good calligraphers and Bhopal has a few. |

You must be logged in to post a comment Login