Books

An Indian Food Writer Breaks Free From Tradition

Nik Sharma walks through his neighborhood in Oakland, Calif., Aug. 14, 2018.

Photo: Preston Gannaway/The New York Times

Nik Sharma’s food is quietly expressive, nodding to the flavors he grew up eating in Mumbai without chaining itself to tradition.

Food writer Nik Sharma was 8 when he made his first pot of rice. It was a disaster.

He found a bottle of Rooh Afza, a rose-flavored concentrated syrup popular throughout South Asia, in the studio apartment in the Bandra neighborhood of Mumbai, India, where he grew up in the late 1980s. Though Rooh Afza is typically mixed into cold water or milk, Sharma had other plans. “I remember thinking, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool if you put the Rooh Afza in the rice so it smelled like roses?’” he said.

The syrup turned the rice an atomic pink hue. It was disturbingly sweet. After a few bites, he threw it out.

His failure was an early cooking lesson: Be bold with flavors. Don’t be reckless.

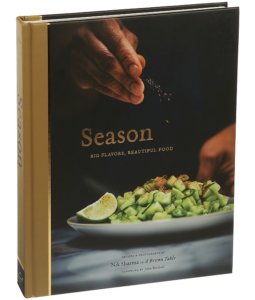

Today, Sharma, 38, has a more measured approach to experimentation, a philosophy he distills in his first cookbook, “Season: Big Flavors, Beautiful Food,”out this week from Chronicle Books. In it, he toys with flavor combinations, chopping unripe green mangoes and stirring them into mayonnaise to make a verdant tartar sauce, and working an extract of caramelized fig and bourbon into glasses of iced chai.

Nik Sharma at his local neighborhood grocery store in Oakland, Calif., Aug. 14, 2018. Photo: Preston Gannaway/The New York Times.

Over the past few years, Sharma has amassed a following between his food blog, A Brown Table, and his cooking column in The San Francisco Chronicle. As with his column, he took all the book’s photographs himself. Their dark, noiseless backgrounds emphasize the elements of composition that matter most: his brown hands, and his food.

The light-soaked kitchen at his home here in Oakland, which he shares with his husband, Michael Frazier, their two cats and a dog, is charmingly chaotic. The spice drawer is clogged with dozens of jars: ancho chile, juniper berries, fenugreek powder. A collection of nearly 400 cookbooks spills from his living room into his kitchen. (“It’s not a lot,” Sharma said, shrugging.) Pieces of black cast-iron cookware, from teakettles to Dutch ovens, dot every corner of the room.

A small wooden box sitting on a high shelf contains talismans from the home he left behind: paperback cookbooks, their pages now yellowed and disintegrating, that he borrowed from his mother, along with his grandmother’s recipes scribbled on notepads.

Sharma’s food is quietly expressive, nodding to the flavors he grew up eating in Mumbai without chaining itself to tradition. Take paneer, an ingredient he feels has untapped potential. It often gets relegated to gloppy bowls of mattar paneer, where it floats next to peas. But it possesses versatility: It is a pretty stubborn cheese, able to withstand heat without collapsing into goo.

“Season: Big Flavors, Beautiful Food” by Nik Sharma. Photo; Sonny Figueroa/The New York Times.

In “Season,”he places charred cubes of roasted paneer in a bed of cauliflower, scallions and lentils. He breaks it up with his hands and folds it into a warm potato salad with cilantro, chives and a cured spicy sausage native to the Indian state of Goa; the paneer eases the jolt of the sausage. He bakes it into a frittata with garam masala, where the paneer retains its rubbery feel, the crumbles scrubbing against your tongue.

“It is wrapped up in so much tradition, but it can be fluid and move across boundaries,” Sharma said of paneer. “I always believe that tradition is great, but it can bind you.”

Sharma knows this bind well. Throughout his life, he has experienced a tension between sticking to tradition and freeing himself from it, between convention and originality.

It is no coincidence that this conflict plays out in his recipes, which are very personal — even autobiographical. They often rely on ingredients found in the Indian dishes of his youth, like that paneer. But Sharma breaks away from familiarity, putting those ingredients in conversation with the food he has encountered in America.

The results defy easy categorization, like Sharma himself. “Mine is the story of a gay immigrant, told through food,” he writes in his cookbook’s introduction, which details his journey from childhood in India to his current life in California as he sought out his place in the world. His cooking helped carry him, providing both direction and comfort along the way.

“My food has always been about wanting people to accept me,” he said. “But I’m also looking for acceptance from myself.”

Sharma spent the first 22 years of his life in the closet. He grew up in Mumbai, born to a Hindu father from the state of Uttar Pradesh and a Roman Catholic mother from Goa. He was not like his schoolmates, whose families had more money than his. He also realized early on that he was gay, though he did not tell a soul. Still, he found himself a frequent target of schoolyard bullies.

Through it all, he cooked. Once he mastered rice, he moved on to a binder of recipes his mother had cobbled together from Indian lifestyle glossies and newspapers. These recipes were not exclusively Indian: He baked a Neapolitan cake using maraschino cherries for the red layer.

“I know people will hate me for that,” he said, laughing. “But that’s all they had in India, so that’s what we used.”

Nik Sharma’s spice drawer, at his home in Oakland, Calif., Aug. 14, 2018. Photo: Preston Gannaway/The New York Times)

He always longed to escape to America, enticed by images of it he had seen in MTV music videos and television shows like “Buffy the Vampire Slayer.”

His moment came in 2002. A student of biochemistry at what was then called the University of Bombay, he landed a scholarship to the University of Cincinnati. He stuffed his life into two suitcases, pressure cooker in tow.

Those years in Cincinnati were freer. Sharma eventually came out to his parents via email; they accepted the news. He cooked often in those days, forging a sensibility that existed somewhere between his upbringing in India and his new life in America. Soon enough, he found himself seasoning his marinara sauce with nigella seeds andbraiding bow-tie pasta with kheemafor weeknight dinners.

He was living in Washington, D.C., pursuing a master’s degree in public policy and working as a medical researcher when he started A Brown Table in 2011; he craved a creative outlet to soften the dual stresses of work and school. Inspired by food bloggers like David Lebovitz and Deb Perelman of Smitten Kitchen, Sharma balanced a point-and-shoot camera on wooden boards that wobbled atop trash cans.

He never imagined that the decision to feature his hands in photographs would be an issue. Within months, anonymous comments began to appear. They were pointed and viciously personal in nature, attacking an aspect of himself he could not suppress: his race. Discouraged, Sharma temporarily stopped blogging, seized by self-doubt.

“One was about the color of my skin being very ashy,” he said. “Then, there were references made to it looking like burnt tar.”

But he gathered himself and resumed writing after a few months, resolving to keep his hands in the photographs. The readers came.

Among those early evangelists was Chitra Agrawal, an Indian-American chef and cookbook author. “Nik has a gift for spinning these flavors he grew up with into entirely new creations that are accessible yet unexpected,” she said.

She was charmed by Sharma’s inventiveness, like his idea to flavor kulfi, a frozen Indian dessert, with pumpkin and sage.

“Growing up, I didn’t care much for Indian sweets,” Agrawal added. “Nik reframed them in a way that was so elegant and inspired.”

In 2014, Frazier, whom Sharma met in Washington, found a job in San Francisco; the two moved across the country, marrying just a few days before they left. Sharma decided to walk away from public policy and begged his way into a job in the kitchen of a pastry shop in Santa Clara.

As his online following grew, Sharma’s work caught the eye of Paolo Lucchesi, the food editor of The San Francisco Chronicle, who gave Sharma a column in 2016.

“Nik’s work — his photos and his writing — represent something new and original,” Lucchesi wrote in an email. “His work is only something he could do.”

Sharma has attracted champions as high-profile as British cookbook authors Nigella Lawson and Diana Henry. Henry, now a close friend, credits him with opening up a world of flavor combinations she did not realize existed.

“He doesn’t have a string of restaurants as Yotam Ottolenghi does, so he has less scope to disseminate his style, but I think Nik really could do for Indian flavors what Yotam has done for Middle Eastern ones,” Henry said. “It is a matter of getting us to see these ingredients in a different and more modern way.”

He also takes dishes of personal significance to him and gives them new life, like his version of bebinca, a traditional Goan dessert of eggs and coconut milk that his grandmother made often. A bebinca usually consists of layers, but he, like his grandmother, makes it with mashed sweet potatoes, condensing them into a mass that resembles pudding. He added a dash of turmeric to accent the vivid orange of the sweet potatoes, and sweetened it delicately with maple syrup as well as jaggery, a fixture of Indian cooking.

The recipe, like others in “Season,” tells the story of who Sharma is: a child of India with his feet in American soil. But he does not want the world to define him in terms of difference. He wants them to know him for the work he produces.

“Being gay, being brown, that’s a part of me I can’t hide,” he said. “But I hope people see me as a writer and a photographer and a cook. These are the things I hope they see me as when I die.”

Nik Sharma’s sweet potato bebinca, in New York, September 2018. Sharma adapted his grandmother’s sweet potato bebinca recipe, adding maple syrup as well as turmeric to bump up its vibrant orange hue. Photo: Linda Xiao/The New York Times.

Recipe: Sweet Potato Bebinca

Yield: 8 servings

Total time: 2 1/2 hours, plus at least 6 hours of cooling

2 to 3 medium to large sweet potatoes (1 1/4 pounds total)

6 tablespoons/85 grams unsalted butter, melted, plus more for the pan

6 large eggs

1 cup/200 grams grated jaggery, muscovado, panela or dark brown sugar

1/4 cup/60 milliliters maple syrup

1 teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg

1/2 teaspoon ground turmeric

1/4 teaspoon fine sea salt

1 (13.5-ounce/400-milliliter) can full-fat coconut milk

1 cup/130 grams all-purpose flour

1. Heat the oven to 400 degrees. Rinse the sweet potatoes to remove any dirt, pat them dry with paper towels and poke several holes in them with a fork. Put the potatoes in a baking dish or on baking sheet lined with aluminum foil. Roast until completely tender, 35 to 45 minutes. Cool completely before handling. Peel the sweet potatoes, discard the skins, and purée the flesh in a food processor. Measure out 1 2/3 cups/400 grams and set aside, saving the rest for another purpose. (The sweet potatoes may be roasted one day ahead and stored in an airtight container in the refrigerator.)

2. Reduce the oven temperature to 350 degrees.

3. Line the bottom of a 9-inch round baking pan with 2-inch sides with parchment paper and grease lightly with butter. Put the pan on a baking sheet. In a large bowl, whisk together the cooled sweet potato purée, melted butter, eggs, sugar, maple syrup, nutmeg, turmeric and salt until smooth. Add the coconut milk and flour and whisk until the mixture is smooth, with no visible streaks of flour.

4. Pour the batter into the prepared pan and put the pan, still on the baking sheet, in the oven. Bake for 55 to 60 minutes, rotating the baking sheet halfway through. The pudding should be firm to the touch in the center and light golden brown around the edges. Remove from the oven and cool completely in the pan on a wire rack. Wrap the pan with plastic wrap and refrigerate to set for at least 6 hours, preferably overnight.

5. Once the bebinca has set, run a sharp knife around the sides of the pan, flip the pan onto a baking sheet lined with parchment paper, and tap gently to release. Peel the parchment off the top. Invert onto a serving dish, and peel off the second sheet of parchment paper.

6. To serve, use a sharp serrated knife to cut the chilled bebinca into wedges. Store the leftover bebinca, wrapped in plastic wrap, in an airtight container in the refrigerator for up to one week.

Nik Sharma’s Bombay Frittata in New York, September 2018. Photo: Linda Xiao/The New York Times.

Recipe: Bombay Frittata

Yield: 6 servings

Total time: 30 minutes

12 large eggs

1/2 cup crème fraîche

1/2 cup finely chopped red onion

2 scallions, white and green parts, thinly sliced

2 garlic cloves, thinly sliced

1/4 cup tightly packed fresh cilantro leaves

1/2 teaspoon garam masala

1/2 teaspoon fine sea salt

1/2 teaspoon black pepper

1/2 teaspoon ground turmeric

1/4 teaspoon red-pepper flakes

2 tablespoons ghee or vegetable oil

1/4 cup crumbled paneer or feta

1. Position a rack in the upper third of the oven and heat the oven to 350 degrees.

2. In a large bowl, combine the eggs, crème fraîche, onion, scallions, garlic, cilantro, garam masala, salt, pepper, turmeric and red-pepper flakes and beat with a whisk or fork until just combined.

3. Heat the ghee or oil in a 12-inch ovenproof skillet, such as cast iron, over medium-high heat, tilting the skillet to coat it evenly.

4. When the ghee bubbles, pour the eggs into the center of the skillet, shaking to distribute evenly. Cook, undisturbed, until the frittata starts to firm up on the bottom and along the sides but is still slightly jiggly on top, about 5 minutes. Sprinkle with the paneer and transfer the skillet to the oven. Cook until frittata is golden brown and has reached desired doneness, 15 to 25 minutes. Serve warm.

Nik Sharma’s cauliflower salad with lentils, scallions and paneer, in New York, September 2018. Photo: Linda Xiao/The New York Times.

Recipe: Roasted Cauliflower, Paneer and Lentil Salad With Cilantro-Lime Dressing

Yield: 4 to 6 servings, as a side

Total time: 35 minutes

For the salad:

1/2 cup green lentils

1/2 cup black lentils

1 small head cauliflower (about 1 pound)

1 10-ounce block paneer, cut into 1/2-inch cubes (about 2 cups total)

1 teaspoon fine sea salt

1/2 teaspoon black pepper

1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil

4 scallions, green and white parts, thinly sliced

For the cilantro-oil dressing:

1 cup extra-virgin olive oil

1 cup tightly packed, fresh cilantro leaves

1 Serrano chile, seeded, if desired

Juice of 1 lime, about 1/4 cup

1 teaspoon coriander seeds

1/2 teaspoon whole black peppercorns

1/2 teaspoon fine sea salt

1. Heat the oven to 425 degrees. Rinse the lentils in a fine-mesh strainer under cold running water and pick out any stones or imperfect beans. Transfer to a medium saucepan and add enough water to cover by about 1 inch. Bring to a rolling boil over medium-high heat, turn the heat to low and simmer, uncovered, until tender but not mushy, 25 to 60 minutes. The cooking time will vary depending on how old the lentils are, so check them every 5 minutes after the first half hour. When they have reached desired doneness, drain through a fine-mesh strainer and set on a clean kitchen towel to absorb any remaining liquid.

2. While the lentils are cooking, roast the cauliflower and paneer: Cut the cauliflower into bite-size florets and transfer to a roasting or sheet pan. Add the paneer. Season with salt and pepper and drizzle with the olive oil, mixing to coat evenly. Roast, stirring occasionally, until the florets and paneer are crispy on the outside and feel tender when pierced with a skewer or knife, 20 to 25 minutes.

3. Meanwhile, make the dressing: Combine all the ingredients in a blender and pulse at medium-high speed until smooth and paste-like.

4. When the cauliflower and paneer are done, transfer to a large bowl and gently stir in the drained lentils and scallions. Taste and adjust the seasoning, if necessary. Drizzle with 1/2 to 1/3 cup of the dressing, to taste, and serve warm or at room temperature. (Store the leftover salad and dressing in separate airtight containers in the refrigerator for up to four days. Shake the dressing before using.)

c.2018 New York Times News Service