Crime

A Top Indian Minister Resigns, But Can #MeToo Reform Government

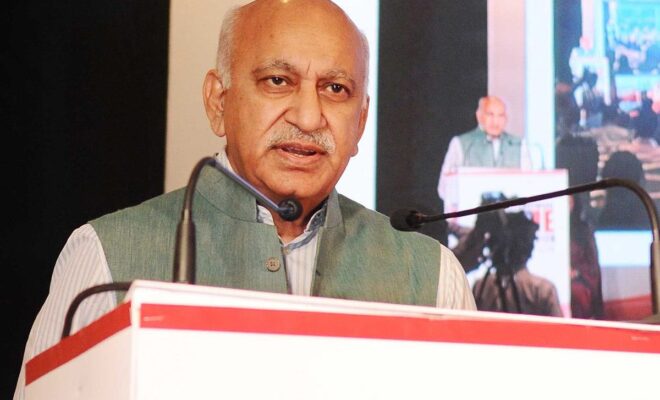

The Minister of State for External Affairs, Shri M.J. Akbar addressing at the inauguration of the International SME Convention 2018, in New Delhi on April 23, 2018.

Akbar, who was appointed minister of state for external affairs in 2016, began his journalism career in 1971, rising to become one of the nation’s most influential editors.

?

Maria Abi-Habib and Vindu Goel

An Indian Cabinet minister quit Wednesday after 21 women came forward to accuse him of sexual harassment, making him the most prominent figure so far to be felled by the #MeToo movement sweeping the world’s largest democracy.

The minister, M.J. Akbar, said he was stepping down to fight his accusers in court. On Thursday, an Indian court will hear the defamation case that Akbar and his 97 lawyers have brought against Priya Ramani, the first woman to publicly accuse him of harassment dating back to a time when he was a prominent newspaper editor.

“I deem it appropriate to step down from office and challenge the false accusations levied against me, also in a personal capacity,” Akbar’s resignation letter said. “I have, therefore, tendered my resignation from the office of minister of state of external affairs.” The position is akin to a deputy secretary of state

After a slow start, India’s #MeToo movement has shaken the country over the past two weeks, as dozens of women in journalism, entertainment, the arts and advertising have accused powerful men in their fields of sexual harassment or assault. The allegations have led to apologies, resignations, professional shunning and in some cases, counterattacks.

Indian women are now facing their toughest battle yet, demanding accountability from the highest echelon of male power: the government.

“As women, we feel vindicated by M.J. Akbar’s resignation,” Ramani said in a tweet. “I look forward to the day when I will also get justice in court #metoo.”

Whether Akbar’s fall sets off a wider reckoning within the country’s political class will largely determine whether India’s #MeToo movement leads to lasting change in the country. India has been plagued by sexual violence against women and poor implementation of existing laws to protect them.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has cast himself as a champion of women, funding more social welfare programs for women and lengthening sentences for rapists. But there have also been disappointments for female voters.

Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party initially stood behind party officials accused of sexual misconduct, as it did with Akbar. Earlier this year, party officials also defended a group of hard-line Hindu supporters accused of the gang rape and murder of an 8-year-old girl from the country’s Muslim minority.

Even supporters of Modi have faced difficulties pursuing cases against powerful members of his party. In Bangalore, a popular right-wing social media commentator, Sonam Mahajan, has spent the past year pursuing a sexual harassment claim against a top aide of Rajeev Chandrasekhar, a business magnate and ruling party lawmaker.

After an internal investigation found him guilty of harassment, the aide used Chandrasekhar’s lawyer to get a judge to impose a gag order preventing Mahajan from talking about the findings or filing charges with the police.

In Akbar’s case, despite the tacit support he received from the Indian government, 20 more women in addition to Ramani came forward Tuesday night to sign a letter accusing the minister of sexual harassment at The Asian Age, the newspaper he started in the early 1990s, and another newspaper.

Akbar “continues to enjoy enormous power and privilege as minister and member of parliament,” their letter read. “When Ms. Ramani spoke out against him in public, she spoke not only about her personal experience but also lifted the lid on the culture of casual misogyny, entitlement and sexual predation that Mr. Akbar engendered and presided over.”

One female journalist said Akbar began their meeting by answering the door in his underwear. Another said he repeatedly grabbed her in the office and forced his tongue against her pursed lips.

At the time, the minister’s accusers were all young women newly out of university. Now some of them are among India’s most powerful women, heading the newsrooms of three English-language newspapers in the country and working internationally at major outlets like CNN and The New York Times.

On Thursday, India’s courts will decide whether to hear the testimony of those women.

Akbar, who was appointed minister of state for external affairs in 2016, began his journalism career in 1971, rising to become one of the nation’s most influential editors.

This week, the Indian government declined to comment on the allegations against Akbar, saying that they were “personal and stem from his time before he entered government.”

Criticism mounted as Modi, who faces re-election in 2019, stayed silent.

When his party swept national elections in 2014, he promised economic growth and social progression for all and more women-centric welfare programs. Despite some reforms, Modi has failed to empower and encourage more women to enter the work force — a goal that is important to achieving a robust economy

Despite rising education rates for women across India, women are exiting the workforce by the millions. In 1990, women accounted for 34.8 percent of India’s labor force; by 2016, that proportion fell to 23.7 percent, according to a World Bank report.

If more women entered the workplace, India could increase its gross domestic product by 60 percent or $2.9 trillion by 2025, according to a 2015 study by McKinsey Global Institute.

“When we looked at women managers, one of the things that was obvious was that whenever they faced harassment, they went back home or their home pulled them back,” said Ranjana Kumari, the director of the Center for Social Research, a Delhi-based think tank.

In India, sexual harassment allegations cut across party lines. On Tuesday, the head of the Indian National Congress’ national student union quit as women accused him of harassment.

The question now is whether the current #MeToo movement can improve the lot of women across India and make workplaces safer, or whether the efforts will peter out as attention fades and the inevitable backlash from India’s patriarchal culture sets in.

Ghazala Wahab wrote a harrowing first-person account of the sexual abuse she said she faced from Akbar when she was a young journalist. Originally from a small city in India, she became the first woman in her family to pursue a career after finishing her studies.

Rather than representing independence, she said, the office became “a torture chamber, I was desperate to get out of, but couldn’t find the door.”

Making public accusations of sexual harassment against government officials is challenging because political figures have influence at many levels of the state in India, including in the courts.

Mahajan, the commentator and television personality hired by the office of Chandrasekhar, the member of parliament, learned that the hard way. Shortly after her appointment a year ago, she has alleged, it became obvious to her that the man who hired her, Chandrasekhar’s chief of staff, Abhinav Khare, was interested in more than her knack for making pro-Hindu posts go viral.

Mahajan filed a sexual harassment complaint against Khare. After a lengthy internal investigation, the employer found him guilty of harassment, she said in a series of tweets.

But Khare recently went to court and, without a hearing or advance warning to her, obtained an order preventing her and her former employer from discussing the case. Khare said in an email that Mahajan’s claims were false and came as he was about to fire her for poor performance.

A spokesman for Chandrasekhar said that Mahajan had received swift and fair justice and that “Mr. Chandrasekhar supports the women who have come out bravely to take on their tormentors and believes they deserve their justice.”

c.2018 New York Times News Service

You must be logged in to post a comment Login