Business

How McKinsey Lost Its Way in South Africa

Dominic Barton, managing director of the storied McKinsey & Company consultancy, in Manhattan, May 16, 2018.

Photo: Sasha Maslov/The New York Times

Had McKinsey vetted the Eskom contract properly, it might have spared itself some of the grief to come regarding the "state capture" allegations involving the Gupta family and former South African president Jacob Zuma.

The blackouts kept coming. The state-owned power company, Eskom, was on the verge of insolvency. Maintenance was being deferred. And a major boiler exploded, threatening the national grid.

McKinsey & Co., the godfather of management consulting, thought it could help but was not sure that it should, according to people involved in the debate. The risk was huge. Could McKinsey fix the problems? Would it get paid? Would it be tainted by South Africa’s rampant political corruption?

In late 2015, over objections from at least three influential McKinsey partners, the firm decided the risk was worth taking and signed on to what would become its biggest contract ever in Africa, with a potential value of $700 million.

It was also the biggest mistake in McKinsey’s nine-decade history.

The contract turned out to be illegal, a violation of South African contracting law, with some of the payments channeled to an associate of an Indian-born family, the Guptas, at the center of a swirling corruption scandal. Then there was the lavish size of that payout. It did not take a Harvard Business School graduate to explain why South Africans might get angry seeing a wealthy U.S. firm cart away so much public money in a country with the worst income inequality in the world and a youth unemployment rate of more than 50 percent.

And a bitter irony: While McKinsey’s pay was supposed to be based entirely on its results, it is far from clear that the flailing power company is much better off than it was before.

The Eskom affair is now part of an expansive investigation by South African authorities into how the Guptas used their friendships with Jacob Zuma, then the country’s president, and his son to manipulate and control state-owned enterprises for personal gain. International corruption watchdogs call it a case of “state capture.” Lawmakers here call it a silent coup. It has already led to Zuma’s ouster and a moment of reckoning for post-apartheid South Africa.

Yet despite extensive coverage of the scandal by the local news media, one question has remained largely unanswered: How did McKinsey, with its vast influence, impeccable research credentials and record of advising companies and governments on best practices, become entangled in such an untoward affair?

McKinsey admits errors in judgment while denying any illegality. Two senior partners, the firm says, bear most of the blame for what went wrong. But an investigation by The New York Times, including interviews with 16 current and former partners, found that the roots of the problem go deeper — to a changing corporate culture that opened the way for an aggressive push into more government consulting, as well as new methods of compensation. While the changes helped McKinsey nearly double in size over the past decade, they introduced more reputational risk.

The firm also missed warning signs about the possible involvement of the Guptas and only belatedly realized the insufficiency of its risk management for state-owned companies. Supervisors who might have vetoed or modified the contract were not South African and lacked the local knowledge to sense trouble ahead. And having poorly vetted its subcontractor, McKinsey was less than forthcoming when asked to explain its role in the emerging scandal.

“I take responsibility,” McKinsey’s managing director, Dominic Barton, said in a recent interview. “This isn’t who we are. It isn’t what we do.” Regrettably, he added, the firm had a “bit of a tin ear” in its early response to the crisis.

Since the Eskom disclosures, much of McKinsey’s business in South Africa has evaporated. Barton has made six trips there to assess the damage and make amends, and McKinsey has asked its 2,000 global partners to repay South Africa, where it is under investigation.

Indeed, the harm to the McKinsey brand is more profound than the fallout from the epochal Galleon hedge fund case almost a decade ago, in which McKinsey’s former managing director and a senior partner were convicted on charges related to insider trading. Neither man acted on behalf of McKinsey.

More broadly, the scandal in South Africa — which has ensnared several other overseas companies — underscores the risks that arise as governments increasingly turn over responsibilities to consultants who operate mostly in secret, with little or no public accountability.

The Lethabo Power Station outside Johannesburg, operated by South Africa’s state-owned Eskom utility, June 23, 2018. Photo Credit: Gulshan Khan/The New York Times

McKinsey built its brand as the ubiquitous adviser to businesses great and small. But in recent years, it has created an increasingly powerful unseen presence as counselor to governments across the globe.

The extent of that global influence is difficult to evaluate because, as a matter of policy, the firm will not reveal clients or the advice it gives.

Even so, by examining government records, along with McKinsey publications and other company documents, The Times found that the firm shapes everything from education, transportation, energy and medical care to the restructuring of economies and the fighting of wars.

McKinsey’s clients include sovereign wealth funds worth more than $1 trillion, as well as what one marketing brochure describes as “defense ministries, military forces, police forces and justice ministries in 15 countries,” where the company consults on such matters as the maintenance and support of “armored personnel carriers; minesweepers, destroyers and submarines; and fast jets and transport aircraft.”

McKinsey “is a hidden, unaccountable power that has a prestigious face,” said Janine R. Wedel, a professor at George Mason University who has written extensively on what she calls “the shadow elite.”

She added, “Think of them as a repository of the most intimate information that governments and others have, from what they are investing in to who wields influence.”

McKinsey refused to work in South Africa until it embraced democracy in the mid-1990s, but records show that it consults for many authoritarian governments, including the world’s mightiest, China, to a degree unheard of for a foreign company. Late last year, two McKinsey partners spoke at a meeting of the state-controlled conglomerate China Merchants Group that focused on carrying out Communist Party directives. McKinsey is also advising the Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, as he seeks to make its economy less reliant on oil.

While confidentiality is necessary in private business, it can become problematic when public money is involved, as in South Africa, or for that matter in the United States, where McKinsey has advised more than 40 federal agencies, including the FBI, the CIA, the Defense Department and the Food and Drug Administration.

Since President Donald Trump took office, McKinsey has greatly expanded consulting for Immigration and Customs Enforcement through that agency’s office of “detention, compliance and removals.” Their contracts with the agency exceed $20 million. Asked about those contracts, a McKinsey spokesman said the company’s work focused primarily on administration and organization and was unconnected to immigration policy, including the separation of children and parents at the border.

Certainly, consulting firms other than McKinsey keep client lists confidential and work for authoritarian governments. And McKinsey has undeniably been a force for good, through its pro bono work and by helping many organizations become more efficient engines of economic growth. As for the quality of people McKinsey hires, many have gone on to run some of the world’s biggest and most successful companies.

That is why McKinsey’s behavior in South Africa is so startling.

The Firm Rewrites the Rules

In 2012, a new class of recruits — the worker bees in McKinsey’s hive — settled in at its office in Sandton, Johannesburg’s financial center, often called the richest square mile in Africa. They were part of a notably diverse group. Given South Africa’s historic battle against apartheid, it was a point of pride at McKinsey that more than 60 percent of the office’s 250 employees were black South Africans. Many described their work as a calling, an opportunity to make a difference in a young and still-struggling democracy.

Years earlier, McKinsey’s South African partners had decided that to be relevant, they had to embrace the public sector, because of its outsize role in South Africa’s economy. But a South African government weakened by corruption also represented a risk to McKinsey’s sterling reputation — a reputation forged by its founder, a math whiz from the Ozarks named James O. McKinsey, and nurtured by his disciple and successor, Marvin Bower.

Over the decades, the firm — that’s what it calls itself — became confidant to chief executives and presidents, simultaneously the secret-keeper of corporate America and its most effective evangelist, preaching the McKinsey way to companies across the globe.

In 1952, McKinsey helped incoming President Dwight D. Eisenhower staff his new administration. Later it helped to set up NASA and helped to invent the Universal Product Code — the bar code. The company was instrumental in Wall Street’s rise as a dominant force in the economy, providing SWAT teams of brainpower to help Merrill Lynch, Citigroup and countless other financial companies adapt and move into new markets.

An office building in Johannesburg where the management consultancy McKinsey & Company’s South African offices are based, June 23, 2018. Photo Credit: Gulshan Khan/The New York Times

There came to be a not entirely hyperbolic narrative of McKinsey’s preordained white-shoe path through the world — the Harvard Business School recruit turned McKinsey consultant turned rising corporate titan. And few companies have a better track record of producing them: Louis V. Gerstner Jr., who oversaw IBM’s turnaround in 1990s, is a McKinsey veteran. So is Sheryl Sandberg of Facebook, and Google’s chief executive, Sundar Pichai.

“So pervasive is the firm’s influence today that it is hard to imagine the place of business in the world without McKinsey,” wrote Duff McDonald, author of “The Firm,” a 2013 book about the company.

McKinsey has had its share of bad publicity, but much of it has focused on people who have already left.

One very public flap emerged in the summer of 1970, when The New York Times (also a McKinsey client over many decades) published front-page articles detailing an explosion in consulting fees paid out by New York City. At the center of the controversy was a young McKinsey partner, acting as an unpaid official in the city’s budget bureau even as the city was spending taxpayer dollars on contracts with the firm.

It looked bad. And while McKinsey was cleared of wrongdoing, the experience helped steer the company away from government work, avoiding the publicity, the ethical quandaries and the generally lower fees that came with public contracts.

But if McKinsey had learned a lesson, it soon began to unlearn it.

By the early 2000s, McKinsey re-entered the public sphere in a major way — and now government contracts and work with state-owned companies make up 16 percent of the firm’s revenues.

There was another lesson being unlearned as well: Work for a fixed fee.

(BEGIN OPTIONAL TRIM.)

In the late 1980s, an up-and-coming partner in McKinsey’s energy practice, Jeffrey K. Skilling, had been part of a committee considering whether payment should be based on delivered results, such as reduced costs.

As Skilling told journalist Anita Raghavan, the panel concluded it would not work, because getting paid based on impact, for example, could give McKinsey an incentive to tell clients to reduce costs even if it was not in their interest. Doing that, Skilling said, “could destroy” the firm.

Skilling — who would become Enron’s chief executive and end up in federal prison after its vast accounting fraud was revealed — saw the ethical trap. A future generation of McKinsey partners came to a different conclusion.

Starting around 2001 or 2002, McKinsey again began to rethink its fee-for-service rule. Its competitors were already changing over. After years of deliberation and study, the firm agreed in 2011 to allow “at risk” contracts alongside its traditional fee structure.

“There’s been client demand for that, clients saying we like that approach,” Barton said. “If you don’t get the results you want, then don’t pay us.”

With this new pay policy and avid embrace of government work, the firm’s South African partners had been handed a seductive vision of the future. Some of McKinsey’s young associates in Johannesburg would end up on the ill-fated Eskom deal. But first, there was an ambitious project at the state-owned rail and port agency, Transnet.

‘Trying to Play God’

McKinsey had worked with Transnet since 2005, embedding itself so deeply that one board member wondered how the agency could ever oust the consultants should the need arise. Still, Transnet remained an underachiever, its ports inadequate, its freight rail system moribund.

Then, in February 2011, Transnet got a new chief executive, Brian Molefe, who had been running the country’s public pension fund.

His tenure began with controversy. The South African media had already linked him to the Guptas, a family led by three brothers who arrived in South Africa a quarter-century ago and became ostentatiously wealthy through a web of businesses, once commandeering an air force base to fly in wedding guests from India.

McKinsey and Molefe set out to revitalize the agency by buying as many as 1,064 new locomotives in what would be the biggest government procurement in South African history. But McKinsey would have to take on a subcontractor, under a South African law requiring companies that worked with state-owned enterprises to have black-owned partners.

According to prosecutors, the Guptas saw these black-empowerment companies as a way to empower themselves, and state-owned companies like Transnet became willing accomplices. Transnet steered McKinsey toward working with a company, Regiments, owned in part by a businessman linked to the Guptas.

But weeks before the winning bidders were announced, McKinsey bowed out, saying the process was moving too quickly.

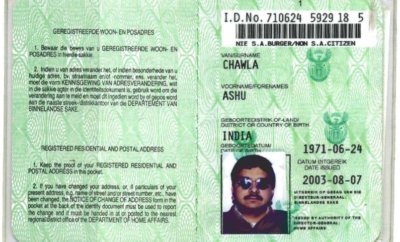

As it turned out, Transet agreed to pay about $1 billion more than the agreed-upon price for the locomotives. And, as leaked documents published last year in the local media revealed, one of the winning bidders, a state-owned Chinese company, paid more than $100 million to shell companies tied to another Gupta associate, Salim Essa.

Although it is unclear what, if anything, Molefe knew about those payments, he left Transnet to search for a new challenge. He found it in 2015 as the chief executive at Eskom.

The power company had long been the public’s favorite punching bag, notorious for its high rates, sputtering from one crisis to the next. Officials worried about getting enough coal, about delaying maintenance to keep electricity flowing. During the World Cup in 2010, Eskom feared that the lights might go out at any moment with the whole world watching.

To address Eskom’s financial troubles, McKinsey and Eskom drew up an audacious new reorganization plan.

McKinsey’s team leader on the project was a popular partner, Vikas Sagar, a stylish, Porsche-driving fitness buff in his 40s, known for hugging colleagues when the spirit moved him and fiercely charting his own course. He was assisted by Alexander Weiss, a serious reverse image of Sagar, who thought little of commuting between his home in Germany and Johannesburg.

McKinsey’s proposal appeared perfect for a company in desperate financial straits. Eskom would pay only if the plan produced savings. Then the consultancy would get a percentage. All the risk, ostensibly, would be McKinsey’s, since it might spend heavily but get nothing in the end.

Yet for all the upside, the proposal had a Trojan-horse quality: Eskom would hire McKinsey not knowing what the final bill would be.

The plan left several McKinsey partners uneasy. Could Eskom absorb and apply McKinsey’s recommendations? And how would a contract with an anticipated payout in the hundreds of millions of dollars be received by South Africans? Also troubling was the fact that McKinsey had won the contract without competitive bidding.

“You are betting the office,” one former partner recalled warning colleagues. If the final payout became public, that official added, “You are going to be slaughtered just for the size.”

The contract’s structure — with the risks it posed for McKinsey — was not universally embraced, either. “Trying to do a 100 percent at-risk contract at Eskom is trying to play God,” a former partner said. “You are really guaranteeing that I can turn around everything, no problem.” To accomplish that, McKinsey might need more political clout and expertise than it could deliver.

Most of McKinsey’s current or former partners who spoke to The Times requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to the media. McKinsey did provide several partners for interviews on the condition that their names not be used. Sagar did not respond to repeated messages seeking an interview, and Weiss declined to speak to The Times.

Concerns notwithstanding, the prospect of a big payday made the contract popular not only in Johannesburg but throughout McKinsey’s global empire. Supporters included two senior partners with oversight in energy and power: Yermolai Solzhenitsyn, novelist Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s eldest son, in Moscow, and Thomas Vahlenkamp in Düsseldorf, Germany. Both declined to be interviewed.

In the end, Sagar and his allies carried the day.

In situations like these, risk managers are supposed to serve as corporate lifeguards, ready to whistle back dealmakers if they expose the company to unnecessary legal and reputational peril. Yet the Eskom contract was approved with less scrutiny than regular public contracts. That was because state-owned enterprises were treated as private corporations, where reviews focused on commercial viability, not political risk.

Had McKinsey vetted the Eskom contract properly, it might have spared itself some of the grief to come. The contract, it turned out, was illegal: The power company had failed to get a government waiver from the standard fee-for-service payment, despite assuring McKinsey that it had done so.

“For the scale of the fee, they were prepared to throw caution to the wind, and maybe because they thought they couldn’t be touched,” said David Lewis, executive director of Corruption Watch, a local advocacy group.

A Mystery Partner Is Unmasked

If McKinsey fell short in vetting the Eskom contract, the same could be said about the scrutiny of its minority partner, a company called Trillian Management Consulting.

McKinsey’s putative marriage to Trillian produced its first awkward moments when its chief executive, Bianca Goodson, showed up angry at the consultancy’s Sandton headquarters on a January evening in 2016. Under McKinsey’s agreement with Eskom, Goodson’s company was supposed to provide consulting support but with only two employees was unsure how to do that.

Feeling ignored and marginalized, Goodson planned to raise her concerns at a meeting of McKinsey partners. Four hours in, she got her chance. But before she could finish, Goodson wrote in an account later submitted to Parliament, a McKinsey team leader abruptly left the room, another partner said not to worry too much about work because she would still get her financial cut, and another made “whipping sounds and gestures,” an apparent inside joke, prompting laughter among the partners.

Goodson left more disillusioned than before she arrived. Two months later, she resigned.

During the internal debate over the Eskom deal, several partners had questioned whether McKinsey knew enough about who precisely was behind Trillian. Now rumors began reaching the McKinsey office that Trillian Management and its parent company, Trillian Capital, might have ties to the Gupta family.

McKinsey knew little about Trillian — a new company, with no track record, that had broken off from McKinsey’s previous minority partner, Regiments, after a business dispute. What’s more, Trillian had refused McKinsey’s requests to divulge its ownership.

Even so, McKinsey chose to kick the can down the road and continue working. What McKinsey did not yet know was that Eskom’s chief executive, Molefe, had placed dozens of phone calls to one of the Gupta brothers during and after contract negotiations.

An influential senior partner in Johannesburg, David Fine, had grown increasingly uneasy about Trillian, according to his testimony to Parliament. One source of concern: Over the objections of two senior partners, McKinsey’s team leader, Sagar, had been meeting with Eskom and Trillian without any other McKinsey officials present.

Eventually McKinsey hired a private investigative firm to dig into Trillian’s background. When that did not produce any definitive leads, Fine began running internet searches on companies named Trillian and found the name “S. Essa” listed as a director. Weeks later, the South African media revealed the majority owner of Trillian as none other than Salim Essa, the Gupta associate whose shell companies had received more than $100 million in the locomotive deal.

On March 30, 2016, McKinsey told Eskom in writing that it was severing its ties to Trillian. But while McKinsey had finally taken a stand, it quietly undercut that decision by continuing to work alongside Trillian — independently, rather than as a subcontractor.

To the consternation of some McKinsey partners, that arrangement continued until the end of June 2016. With the local media revealing ever more of the Gupta family’s influence, Eskom — not McKinsey — prematurely terminated the contract. Molefe resigned that November. Molefe did not respond to requests for comment for this article; a lawyer for the Guptas declined to comment.

The abbreviated tab for barely eight months of work: nearly $100 million, with close to 40 percent going to Trillian.

In the United States, with an economy more than 50 times as big as South Africa’s, a contract that size might have gone unnoticed. But in South Africa, millions of dollars flowing out of a struggling public utility and into the pockets of consultants driving Porsches and Ferraris created an unsavory image that required a response.

Yet McKinsey kept quiet, one of many decisions the firm would come to regret.

A Surge of Public Scrutiny

Late the next year, South Africa’s National Prosecuting Authority would deliver a stinging summation of the Eskom case. McKinsey, the prosecutors would allege, had been instrumental “in creating a veil of legitimacy to what was otherwise a nonexistent, unlawful arrangement.” That arrangement, in turn, allowed a company controlled by the Gupta associate, Essa, to profit.

That conclusion was based in part on a letter obtained by a widely respected human-rights advocate, Geoff Budlender, who had been asked to investigate Trillian, including its ties to McKinsey. For the first time, McKinsey was being publicly held to account.

Budlender asked to interview McKinsey but was told to put his questions in writing, which he did. In response to one question, McKinsey denied working “on any projects” with Trillian, as either a subcontractor or a black-empowerment partner.

With his trap laid, Budlender pounced. He attached a Feb. 9, 2016, letter from the McKinsey team leader, Sagar, to Eskom. “As you know,” Sagar had written, “McKinsey has subcontracted a portion of the services to be performed” to Trillian. The letter went further and authorized Eskom to pay Trillian directly, rather than through McKinsey, as was customary for a subcontractor.

Asked to explain the conflicting answers, a McKinsey lawyer, Benedict Phiri, took weeks to respond, saying he needed to speak with his colleagues. Finally, he wrote that, given ongoing legal disputes, it was “inappropriate” to comment.

Budlender concluded that McKinsey’s denial was false. “I have to say that I find this inexplicable, particularly having regard to the fact that McKinsey presents itself as an international leader in management consulting and given the widespread public interest in this matter,” he wrote.

In the interview with The Times, the McKinsey managing partner, Barton, said the office leadership in Johannesburg had been unaware of Sagar’s letter and had only learned of it from Budlender. But three current or former McKinsey partners told The Times that Sagar’s German colleague, Weiss, and the firm’s lawyer, Phiri, also knew of the letter.

McKinsey’s lawyers said that the letter should never have been sent. Even so, they said, the authorization to pay Trillian referred to another, much smaller contract, and it was predicated on Trillian’s meeting certain conditions.

In late 2017, a parliamentary committee began calling witnesses as part of its own investigation of state capture. One witness was Goodson, the former Trillian executive, who said she had been told soon after being hired that Essa owned Trillian. She also testified about meeting Sagar and Essa in Melrose Arch, a wealthy enclave with high-end retail and sidewalk dining where deals are made.

McKinsey sent Fine, who withstood nearly four hours of questioning. He addressed criticism head on, beginning with the size of the contract. “We should have absolutely had a fee structure that was capped,” he said.

Fine, who had no role in the Eskom contract, said he had been assured that Eskom did derive measurable benefits from McKinsey’s consulting. Yet his comments betrayed an element of doubt. As a native South African, he said, he couldn’t help asking himself, “If these benefits were there, why then has the price of electricity gone up and has the liquidity position of Eskom deteriorated?”

Barton, in his interview with The Times, insisted that his firm helped Eskom solve important problems. He expressed frustration at the overarching narrative that McKinsey took money for little work. “There was real work being done,” he said.

Grieve Chelwa, an economics lecturer at the University of Cape Town, said in an interview that McKinsey’s top ranks in South Africa were overwhelmingly filled by Europeans who “may not have had the political antennae” to pick up potential problems.

“The less charitable interpretation is that they knew,” said Chelwa, until recently a fellow at Harvard’s Center for African Studies. “They made a risk calculation that we know what is going on or we have an idea what is going on, but then there is 1.6 billion rand to make, and what is the probability that all this falls in our faces? They made that kind of calculation and they said, ‘OK, the risk is worth doing,’ and they did it.”

Hard Lessons Learned

It is a risk McKinsey now regrets taking.

The advocacy group Corruption Watch referred the firm’s conduct to the U.S. Justice Department for possible violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. McKinsey declined to say whether federal investigators had contacted the firm; the Justice Department declined to comment. The National Prosecuting Authority in South Africa has frozen the proceeds of the Eskom contract, pending the completion of the government’s investigation. And several banks and corporations, including the South African arm of Coca-Cola, have said they will not do business with McKinsey until investigations are concluded.

McKinsey vehemently denies breaking any laws and says that this view has been validated by a monthslong internal inquiry involving more than 50 lawyers reviewing millions of documents and emails.

The firm does admit mistakes. McKinsey will now give state-owned companies the same scrutiny it would government agencies or ministries. That policy may have a major impact in China, where McKinsey has advised at least 19 of the biggest state-owned companies as well as the country’s powerful planning agency.

In a statement, McKinsey said that it was “not careful enough about who we associated with,” that it should not have worked alongside Trillian after cutting its ties and that it did not communicate properly with Budlender. “We are embarrassed by these failings, and we apologize to the people of South Africa, our clients, our colleagues and our alumni, who rightly expect more of our firm.”

At the end of June, Barton, 55, will step down as previously planned. McKinsey’s nearly 600 senior partners voted to replace Barton with Kevin Sneader, a British citizen. Last weekend, as The Times was preparing this article after weeks of questioning McKinsey about its secretive culture, the Financial Times published an interview with Sneader, who said the firm could no longer “hide from the outside world.”

Sagar has left the firm with his full benefits in place. Weiss has been sanctioned, although McKinsey declined to say what that involved. The firm’s Johannesburg lawyer, Phiri, resigned, and the head of McKinsey’s Africa practice was transferred to Hong Kong.

Fine, who now leads McKinsey’s worldwide public-sector practice in London, cast the fallout from Eskom in personal terms. “I have seen the anger and disappointment in my clients’ eyes,” he told the South African Parliament.

He added, “I’ve experienced rejection from people that I really love and trust, and that’s been hard.”

© 2018 New York Times News Service

You must be logged in to post a comment Login