Arts

Foreign Art Comes Calling

"Lately we've seen so many mediocre works drum up immense publicity simply on the strength of the origin of the artist."

|

In recent years, Mumbai, the mecca of Indian capitalism, has begun opening its fat wallet to art. But art critics and observers have noticed a noticeable bias toward the works of foreign artists, especially pieces with Indian touches. Renowned for its unique black-and-white-prints, Mitterbedi’s studio at Colaba in South Mumbai is a favorite haunt of artist-photographers. Gayatri Bedi, a daughter of the proprietor of this 52-year-old studio, is struck by the heightened interest in foreign artists in the city.

Having worked with famed photographers of Indian as well as foreign origins, Bedi is astonished by the extent the media and the public are stirred by exhibitions of foreign artists, as opposed to Indian ones “If the art is great, or the artist famous, it would be make sense,” says Bedi, shaking her head. “But lately, we’ve seen so many mediocre works drum up immense publicity simply on the strength of the origin of the artist.” Indian exhibitions are particularly advantageous for foreign artists, she says: “For photographers, it’s definitely a lot cheaper to have their prints done here and if they’re displaying their works in local galleries and can manage a good media response, then often the studios may not even charge them anything at all in exchange for a bit of the limelight.” Art critic Abhijit Tamhane concedes the media are exceedingly generous with foreign artists, perhaps out of the inherent Indian hospitality toward guests: “I would have to admit that the local media seems to adopt a nicer attitude towards foreign artists exhibiting here as compared to local artists.” Australian Photographer Sam Phelps

Inspired by a friend’s observation that the appearance and tools of Mumbai’s fire-brigade may well be the last remnants of the city’s history in this rapidly-advancing metro, Phelps decided to capture this historical record on film. Although his previous background was in the area of fashion and commercial photography, one glimpse of the Mumbai fire-brigade was enough to entice this photographer to spend over a month in the Indian business-capital, which, he says, “took a lot of getting used to.” In the end, however, Phelps found that putting up with the, “stench of open sewage,” was well worth it. Eager to take in the Indian experience when he first arrived in Mumbai, Phelps says, he experimented with different Indian cuisines, including dining at street-stalls, which he doesn’t recommend, after he “ended up spending days in bed with a bad stomach-bug.” Even so, Phelps enthusiastically recommends Mumbai’s restaurants, “Indian cuisine has so many complex and delicate flavors,” raving about a dosa diner he visited near Victoria Terminal station in South Mumbai.

Securing official permissions didn’t pose a problem for the Australian photographer, who rather enjoyed the “smooth process” of working in Mumbai. Mumbaites might raise their eyebrows, but somehow, Phelps had it easy: “I met the chief of the fire-brigade, gave a presentation of my work and stated my intent. He liked the idea, signed a permission form and allowed me access to all area, including the burnt-out shell of buildings.” Phelps was overwhelmed by the publicity his exhibition at the Piramal Gallery of Mumbai’s prominent National Centre of Performing Arts at Nariman Point generated. The gallery is well-known for its displays, which have included the works of leading Indian and international artists and houses a rare collection of the works of renowned photographers, such as Judith Mara Gutman, August Sander, Asvin Mehta and Raghubir Singh. “I had about five interviews and articles printed,” said Phelps, noting that the subject drummed up immense public curiosity. Stunned at the revelation that firemen figured “pretty-low on the Indian social-ladder,” Phelps claims that people who came to the show “thanked him for depicting these guys as heroes,” adding, “A lot of professional photographers attended and surprisingly there were many delightful accounts of the display in the press.” He limited seven prints of each fire-brigade portrait, priced upwards of $200 each. French Dramatist Julien Mulot

Julien Mulot came to India on a holiday with friends a few years ago. He was so moved by the country that he decided to stay for personal insight – to see the country, not as a tourist, but as a resident. Though his travels had taken him to cities like Varanasi and Goa, he decided to live in Mumbai as, “this Indian city offers the closest parallel to Western life.” But his experiences in those two years, which he spent in Malad were so “intoxicating,” says Mulot, that, “I wanted to share them and when destiny led me to Fanny Gloux, who had some directorial experience to offer, we thought it would be a good idea to work on a monologue that captures a foreigner’s experiences in Mumbai.” Gloux explained that the first half of Des etoiles sur la terre, the monologue that Mulot eventually staged, “was written totally out of Julien’s experiences in the city, which most foreigners who stay here would relate with.”

Mulot said it was really hard for him to get used to the noise of the city’s traffic. “Living in Malad,” Mulot admits, “is not like living in Colaba, and sometimes I’d even walk past cattle on the road.” Mulot’s monologue chronicles his observation of the hectic pace of Mumbai. Running his hand through his dark hair, Mulot shakes his head as he speaks of, “the clubs, the parties, the night-life, the work, the beggars, the heat…” Mulot was also captivated by the eunuchs on Mumbai’s streets and the fact that they have social and religious relevance in India, which he says, “they wouldn’t in any other part of the world.” Mulot followed a member of this group, video-taping, “Simran’s experiences,” which eventually formed some of the graphic images that were flashed on the screen as Mulot delivered his dialogue. Gloux is staying on in Mumbai as a consequence of her banker-husband’s work assignment, but Mulot candidly admits that he’s glad to be returning to France soon to continue his career. “It’s a crazy city,” says Mulot who enjoyed the experience of exploring Mumbai at a deeper level. One episode he recalls in his narrative is about a beggar girl who was thrilled to receive a little attention from him, because, “people here are so indifferent that they would not stop for a second to talk to a little girl selling flags or just holding her small hand out for alms.” Although his show attracted many French expatriates, Mulot was stunned to discover that it also caught the attention of the media and Indian audiences as well. Though the whole monologue was delivered in French and subtitled in English, Mulot also spoke a few lines in Hindi. Mulot chose the Alliance Francaise Theater to stage his monologue about India simply because, he felt, it would probably “speak more to a French audience.” But the response he received and the curiosity it generated locally, led him to consider local theaters the next time around.

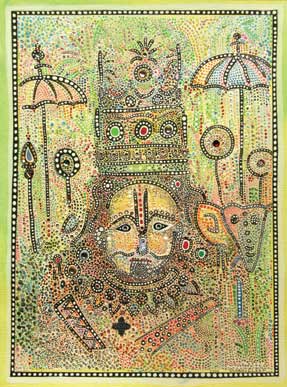

Jeweler Olaf Van Cleef Scion of the Van Cleef dynasty (of Van Cleef & Arpels) whose association with jewelry goes back over a century, Olaf Van Cleef has been visiting India for over 35 years now. Van Cleef says that it was his love for jewelry that drew him to recreate the images of Indian Gods and Goddesses. “Every time we visited a temple, I would marvel at the statues of Indian deities, which are usually adorned with a lot of jewelry from head to toe,” says Van Cleef, explaining that his love for jewelry may have been inherent, as his mother would sport five carats of diamonds on one hand and seven carats on the other. Van Cleef’s love extends to all quarters of India, especially to Pondicherry, which he feels is the most spiritual part of the country, though he also has fond memories of, “the spice market at Cochin and the Elephant market near Patna.” Of Mumbai, Van Cleef says, “I love Mumbai, especially sights like the sunrise at the Gateway of India near the Taj Mahal Hotel, the parrots and the many stalls at Crawford Market and the glimmering Zaveri Bazaar.”

Van Cleef has been exhibiting his works in India for some time now, but Mumbai had never been a destination of choice for such exhibits. However, this year, Van Cleef chose to display at an exhibition hosted by the Concern India Foundation and to give all its proceeds to the foundation for its programs. Speaking of Van Cleef’s work, Manob Tagore, a close-friend of the artist and a descendant of the illustrious Indian poet, Rabindranath Tagore, said, “It’s amazing to watch how Olaf’s art captivates visitors at the gallery.” Tagore said people stop and stare at the works on display, “almost as though they are entranced and they marvel at the vibrancy of the stunning colors.” Van Cleef has experienced the awe that Tagore speaks of. “Many times, visitors cannot believe that I use candy-wrappers of 1 mm size to decorate these paintings,” he remarks, explaining that his Indian collection of deities and architectural works are “ornamented with chocolate-wrappers from all around the world and then crystallized by elements of Swarovski crystals.” Tagore is not sure if it’s the Hindu figurines or Indian architecture or simply the bright and striking workmanship that draws Indians to Van Cleefs’ work. “The first time I saw these creations, I was so awe-stricken by this man’s genuine love for our country that I was the one who suggested he exhibit his work,” said Tagore.

|

You must be logged in to post a comment Login