Opinion

Rahul Gandhi May Have Clintonesque Probem

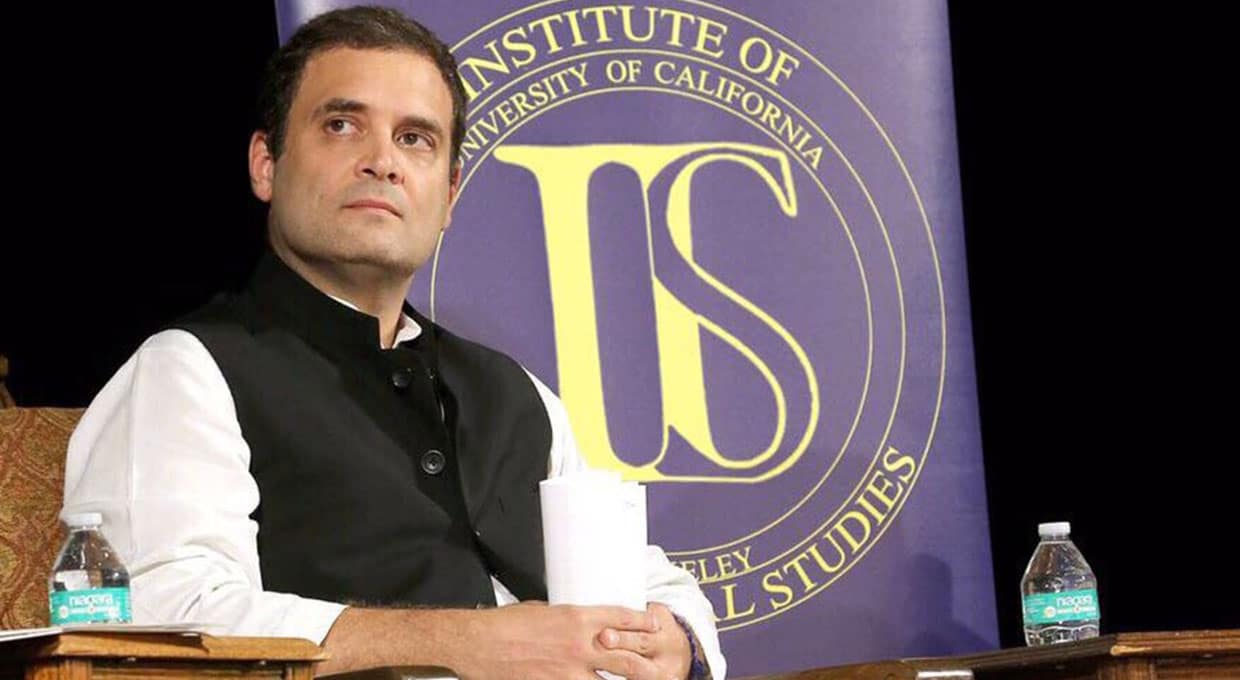

Rahul Gandhi at the University of California at Berkeley.

Photo: IANS

Rahul Gandhi, whose father, grandmother and great-grandfather have all been prime ministers, is discovering, just as the Clintons did, that pedigree and legacy can be a problem.

Last week, in a sparsely decorated, nondescript hall of a midtown hotel in New York, somewhere to the side of a silver tray heaped with stale samosas and sweetmeats, a young man in his 40s sat awkwardly with a man from his father’s generation. The two were posing for selfies with enthusiastic non-resident Indians.

Rahul Gandhi, the man who is expected to take charge of India’s main opposition party this year, and Sam Pitroda, a Chicago-based engineer from Gujarat (credited with bringing the telecom revolution to his native country in the 1980s), reminded me of how a bride and a groom look at a typical Indian wedding reception. Forced to take seats on velvety “thrones” with shiny gold edges, they smile wanly at the serpentine queue of guests that trails past, pretending to be cheery, when all they really want is for everyone to buzz off so that they can hit the champagne.

When a couple of us walked up to say hello to Gandhi at the hotel, he shuffled his feet and barely managed a grimace before he turned away. His two-week tour of the United States, clearly aimed at recasting his image both at home and abroad, had seemingly done nothing to make him more approachable or relaxed with the Indian media. Suspicion of mainstream journalists is the one thing he has in common with his political nemesis, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, but with one critical difference. Modi is the master of the message, an accomplished communicator (as Gandhi himself admitted on his U.S. visit) who is able to bypass the media. The Congress party leader, by contrast, has been parodied, vilified and mocked – sometimes fairly, sometimes unfairly – in large part because of his poor instinct for brand management and his lack of sociability.

Gandhi’s journey through the United States trawled through Ivy League schools, unforgiving international newsrooms and inquiring think tanks, and included meetings with the Indian diaspora. But is it really what he needed to revive himself and the diminishing Congress party? In 2014, the Congress party tanked to its lowest-ever representation in the Indian Parliament since independence in 1947. With no predictable electoral wins around the corner, conventional wisdom would have demanded more of Gandhi at home in India than abroad in the United States.

Strictly speaking, Gandhi is far too old to be brought out at a politician’s version of a debutante ball. Yet this may have been the first time the Western world really saw (and heard) him clearly. And let’s grant him this; it’s also the best press he has gotten in India in years. On the record, Gandhi kept his focus on economic issues such as the jobs crunch in India – and how working-class anger may explain the rise of both Modi and President Donald Trump. His on-background interactions are reported to have underlined concerns about a rising authoritarianism; he often compared India under Modi to Turkey under Erdogan, according to many who met him. He admitted, perhaps for the first time, to the flaws in his own party, conceding that “arrogance” had caused it to trip up. The general consensus in India is (whether one agrees or disagrees with his comments) that his performance was decent or, at the very least, not bad.

“I think it struck a chord back home because India witnessed an unadulterated Rahul Gandhi whose message wasn’t distorted by the press or political opponents online,” Milind Deora, the urbane, well-connected former member of Parliament from Mumbai who organized Gandhi’s tour, told me. “The lesson for the Congress is to engage with key constituents more frequently and directly.”

But Gandhi only has to look around at the United States to understand what part of his positioning remains flawed. The disdain for the “establishment” politics of Hillary Clinton – which explains the rise of Bernie Sanders on the left and Trump on the right – should be especially instructive for Gandhi, whose family, like the Clintons, is seen by many voters as an entrenched, entitled symbol of a corroded system. Gandhi, whose father, grandmother and great-grandfather have all been prime ministers, is discovering, just as the Clintons did, that pedigree and legacy can be a problem – especially when contrasted with Modi’s personal story of a self-made man rising from being a tea vendor’s son to the highest political office in India. Even in the United States, the one issue Gandhi continued to wrestle with is the question of dynasty politics in India.

Like the United States’ Democratic Party, which has been struggling with fund-raising despite an energized Anti-Trump sentiment, it’s not clear that the Congress party will be able to channel the economic discontent among Indian farmers or the restive youth. Like the Democrats, the Congress party is grappling with a ferocious surge of nationalism-as-political-credo and hasn’t quite decided how to define itself against it. And like the Democrats, the Congress party is faced with the charge of elitism in a new era of politics defined by social media, fake news and the power of narrative over nuance. Much like American liberals who have yet to create a political narrative that goes beyond what they hate about Trump, the Congress party has a long laundry list of differences with Modi but remains mired in confusion about what story it wants to tell as its own. How much of the current populist wave is it willing to ride? And if it doesn’t seek the crest of populism, will it remain consigned to the troughs?

Gandhi’s U.S trip may have been a therapeutic break from the usual domestic sniping and media criticism, but he should have brought home a lesson or two from the world’s oldest democracy to its largest.

At the New York event, an New York Police Department official who was ushering us through turned out to be a Muslim of Indian origin. He confided that his father had been an old Congress voter, but he didn’t feel all that optimistic about Gandhi’s prospects. “Rahul must know even medicines come with an expiration date; if he wants to be effective, he needs to learn and act fast.”

Barkha Dutt, based in New Delhi, is an award-winning TV journalist and anchor with more than two decades of reporting experience. She is the author of “This Unquiet Land: Stories from India’s Fault Lines.”

© Washington Post

You must be logged in to post a comment Login