Arts

Train In India

If you allow yourself to submit to India, it stimulates you into experiencing a whole new eco-system of cultures, values and ways.

|

On the platform of Margao Train Station in Goa, a middle aged Caucasian man looked a tad disgruntled and confused. A fellow tourist, I exchanged greetings and figured that he was British from his accent.

I learned that he had been ejected from a train for which he had purchased a ticket online. He tried arguing with the officials, then pleading that he be allowed to pay a fine to continue his journey. But to no avail; he was ordered to disembark at the Margao station and buy a ticket for the next train. Gregory Roberts writes in Shantaram that it is not easy to “win in India” and that one can only “be in India” to survive it. Too bad I had not read Shantaram before my journey. I was in India on the last leg of a 12,000 km trip hitchhiking, biking and traveling by train from Beijing to Mumbai, retracing the ancient silk route. Moods, invitations and attractions veered me off route several times. I found it addictive to travel by train in India. From the Himalayas to the Adam’s Bridge in the South, India is splendidly vast and lucidly contrasted. The colors and rumblings of the Indian Railway establish a coherency that connects its vast land and people. In the three months I spent on the trains, I heard accents change, styles differ, and yet, all Indians seem threaded by a commonality at their core.

My first train ride from Amritsar to Mumbai was initially painful and scary, but I soon came to enjoy myself immensely. I slept on the floor between the doors in the second-class sleeper coach. The floor was messy, so setting my backpack on the ground and lying on the floor took some courage for a Canadian Indian. But once I had made myself comfortable on my sleeping bag, I received plenty of smiles. Everybody headed to the washroom waved and greeted me. Their acceptance came as a welcome surprise. The next time I traveled overnight, it did not bother me at all. As a matter of fact, I even had a friend from New Zealand sleep next to me on the floor, attracting even more attention. One passenger took sympathy on me for not lacking proper reservations and enlightened me on the methodology of baksheesh, a gentler term for bribery. I realized the importance of these tips very quickly. The ticket conductors on board are invisible. They are totally isolated from the conversations, troubles and concerns of passengers. They zoom in and out of coaches like administrative zombies. I learnt to offer baksheesh when my seat was on a “wait list.” I must have ended up paying baksheesh to over a dozen railway officials all over India during the course of my trip. Every official I bribed said he liked me and gave me a discounted “special price.” After the deal, they chatted with me, reminisced about their families and their knowledge about Canada and the USA. I departed with the addresses of three of them and with tea they bought for me with my gratuity. I insisted that one of them explain to me the process to reserve a seat in the general class in the tourist section. Despite his detailed explanation, I was unable to fully comprehend the reservation and ticketing process. Yet, like a howling wild animal, the Indian railway runs through the jungles of the nation, making the remarkably diverse cultures and states in the country rhyme. The cost of a sleeper class from New Delhi to Mumbai (crow distance = 1157 Km) is less than $10. Air conditioned seats on the same journey run around $40. A round trip with up to eight destinations knocks the price to half. Every year ticket prices are declared in the railway budget, which is followed religiously by the media. With 1.6 million employees, roughly the population of Philadelphia, the Indian Railways is the world’s largest employer. It transports some 16 million passengers daily, more than the population of many prominent European countries. It is fair to say that India moves on trains.

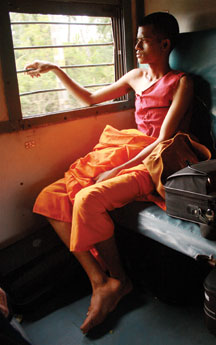

India is the seventh largest country in the world, but it offers no personal space. A coach may carry 10 times the number of people as available seats. On a trip from Madurai to Chennai, I discovered there was hardly any space for anyone to even breathe. I guess physical closeness leads to emotional bonding. There were so many of us in that congested compartment that it was natural for us to establish relationships. I became a son, brother, or uncle to many and, consequently, a stranger to no one. It is entirely normal to be offered food and beverages by strangers. And it is acceptable for strangers to grab a magazine or comic from your bag. It is even appropriate to photograph people without their consent. Indeed, people seemed excited about being photographed. The size of the camera I held only catalyzed the animation before me. Businessmen, workers, children and beggars seemed equally open photography subjects. Some would voluntarily pose to start a conversation. And conversation was available in plenty. The purity of the Radha-Swamis of Beas, the income tax status of pao-bhaji and paan-bidi sellers, the lack of pace in the Indian cricket team’s seam attack, the history of the Syrian Christians in Trivandrum and the efficiency of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s government were all debated endlessly. It was not long before almost everyone would indulge the personal questions: why am I traveling alone? Why I am traveling in India? For that matter, why in the world am I traveling in the first place? The openness feeds the inquisitiveness, which feeds conversations and sharing. On a train to Varanasi a young man conversed with me as we took in the racing paddy fields of Orissa. He was abruptly shaken by a phone call, after which he lapsed into silence. His eyes teared up and he was visibly sad. I was in a part of the world where one gets adopted for the smallest reasons in the easiest of ways.

Since I had become acculturated over months in the ways of the place, effortlessly I probed the reasons for his sadness. He held back his tears to relate to me that while volunteering for a non profit in Bhubneshwar, his father in Bharatpur had sadly passed away. He wept in his hands for a couple of minutes before he managed to sit back and hold his tears. He told me about his Banjara tribe and his head-of-the-tribe father. He related to me his education, his childhood, how his father argued with the family for him to become the first graduate and then post-graduate in the tribe. Mann Singh, the profoundly educated Banjara, and I, had connected. Over the course of a few hours, our relationship went from strangers to brothers who would eat together from a plate. In hours his pain became mine. He relived with me several moments he had spent with his father. Varanasi is a city where people go to die. I went to Varanasi with stories and memories of Mann Singh’s dead father. He laughed while telling me stories before I got off. In that journey, I was accepted, approved and adopted by him. Mann Singh’s India has a history that rhymes in our encounter. India has always accepted the other, embraced it and ultimately adopted it in some form. In return, it makes you do the same. It changes you for good. Or better.

My train travels ended soon after Varanasi. I returned to Toronto with an altered new self that was in many ways redefined by those moments on the trains. Outsiders often complain and are discomforted by the overwhelming presence of smells, sounds and people in India. They can be frustrated by the beggars and eunuchs pleading for money. There are many things in India that are annoying. However, these very reasons for resistance can spontaneously become the cause for submission. The phenomenon that is India, crushes any external voice that challenges its ways. It evolves, and is evolving, from within. If you stay and submit to India, it stimulates you into experiencing a whole new eco-system of cultures, values and ways. These norms might disorient a foreign eye, but they thrive in India. They simultaneously overwhelm and embrace any outsider, even the Britisher I encountered on Platform No 1 of the Margao Train Station. I helped translate for him as he talked to the station master. The officer listened patiently to the whole story, his chin down and eyes looking up at me. Finally, he took his printed online ticket and scribbled something in Konkani. Then, he said, politely in English: “Saar, show this to the TT gentleman in the train. And get off wherever you want.”

|

You must be logged in to post a comment Login