Politics

The Ongoing Effect of Empire in Britain

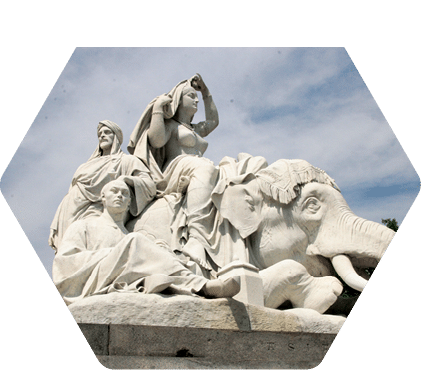

Violent arrivals: British East India Company. Photo: Francis Hayman, Wikimedia

Considerable attention has been directed to the plight of EU immigrants living in the UK following the Brexit vote.

Considerable attention has been directed to the plight of EU immigrants living in the UK following the Brexit vote, not least their role as “bargaining chips” in Britain’s forthcoming exit negotiations from the EU. Less attention has been paid to the government’s ongoing discriminatory immigration policies against its own citizens.

If you marry, as I did, a non-British or non-European spouse, make sure you have a minimum income of £18,600 (or £22,400 if you have a child). You’ll also need thousands of pounds of additional cash for visa fees, biometric testing, and the newly-introduced £200 annual “health surcharge” if you want to have the privilege of remaining in your own country with your spouse and not be forced into exile or a life apart from your family.

Such policies reveal a state that, in order to ensure its welfare and security, is capable of rendering all of its citizens into what the philosopher Giorgio Agamben has termed “bare life”: individuals who are denied the protection of law and whose lives are therefore disposable.

In recent decades, the net of those reduced to “bare life” has widened to capture the white middle-class as well as the marginal sections of the population who are working-class or non-white. But the British state, through its empire, has a long history of reducing people – often entire populations – to this state of powerlessness. Few people today seem to remember or acknowledge this.

In a YouGov poll conducted in January 2016, 43% of those surveyed regarded empire as a “good thing”. In a similar poll carried out two years ago, 49% of respondents thought that “former British colonies are now better off for having been part of the empire”. Disturbingly, a third of participants also wished that Britain still had an empire.

Such attitudes reveal a lack of understanding of the nature and effects of colonial conquest and rule, spurred by insufficient education about the realities of empire. Historical analysis of empire has also tended to evaluate empire either “neutrally”, or offer a triumphalist narrative that heralds the benefits of empire for Britain while ignoring its devastating impact on the peoples whose lands were taken, cultures transformed, and economic well-being was decimated.

The Reality

Take the case of India. In the 17th century, it produced a quarter of the world’s income – equal to the whole of Europe combined – and its per capita GDP was 80% that of Britain’s. But standards of living in India fell rapidly following what the historian William Dalrymple has described as “the supreme act of corporate violence in world history” — the gradual conquest, plunder and subjugation of India by an English trading company with one of the most powerful armies in the world.

In just the half century following the dissolution of the East India Company and the imposition of crown rule in 1858 – the start of what is popularly known as the “Raj” — per capita income declined by over 50%, life expectancy fell by 20%, and between 12 million and 29 million Indians died in famines that the colonial regime largely facilitated instead of alleviating. So rather than leaving the colonized “better off,” empire led instead to the creation of what some now term the “third world.”

While the British liked to boast that they were bringing the “rule of law” to lawless peoples, they instead supplanted indigenous systems of law with ones that were alien, discriminatory and imposed by force. Colonial regimes also frequently suspended the “rule of law” in the face of real or imagined threats to their security. This meant that British colonies largely devolved into states of exception, in which the colonized were reduced to “bare life.”

Them and us

Violent arrivals:British East India Company.Photo: Francis Hayman, Wikimedia

There is another reason why we continue to regard empire in a positive light: the British largely see the effects of empire as being one-sided, as affecting “them” and not “us”. But in Britain, even supporters of empire have long been troubled by the dangerous effects of empire on Britain itself. It’s not possible to govern a quarter of the world’s population despotically (as was the case at the height of Britain’s empire) without profoundly shaping Britain in the process — including methods of managing “undesirable” segments of the population.

Such methods include the reduction of British citizens and their families to a state of “bare life.” This is apparent in policies ranging from the immigration rules that have affected my own family, to the government’s austerity measures, which a recent UN report declared a breach of international human rights. Empire is no longer merely “out there” in other parts of the globe. The disdain for human life that underpinned it has been brought “home.”

The new British prime minister Theresa May has promised to retain at least some of the protections provided by EU law, such as those for workers’ rights — at least during her premiership. But when Britain “takes back its sovereignty” upon leaving the EU, even more segments of the population will undoubtedly find themselves subject to a sovereign “rule of law” that has been constructed in conjunction with the subjugation of large swathes of humanity. Now, we are all, potentially, “bare life.”

The author is senior lecturer in Indian and Colonial History, University of Liverpool.

Reprinted from The Conversation