Arts

The Colors Of Desi

One in nine Indian Americans is biracial.

|

Genetics is their football and they are out to smash all stereotypes. Races meet and merge in their faces. Long Indian eyelashes cover eyes of pristine blue; glowing ebony skin mixes with Caucasian features. Think Halle Berry, think Tiger Woods, think Saira Mohan, think Lisa Ray, Sarita Chowdhury.

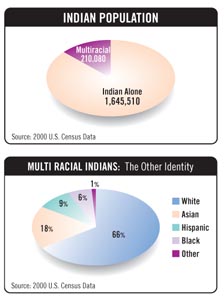

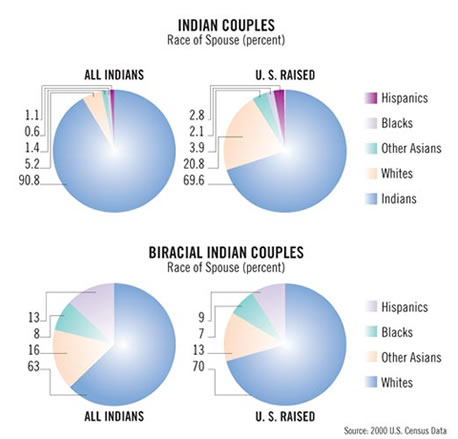

These are the faces of the future, faces where cultures and races blend, where different essences combine to create a new fragrance haunting but you’re never quite sure of what it is. Musk? Attar? Tuberoses? Or a mix of all? Welcome to the brave new world of children of intercultural unions, families that defy the old rules – hopscotching over national borders, criss-crossing cultures and a babble of languages to create a new race, a new reality. It’s almost as if the great showman in the sky, sitting in his director’s chair and bored with the same old, same old, is experimenting and bringing some pizzazz to the leela or celestial play. Biracial marriages, barred by law in 16 states just 40 years ago, are now commonplace in America and the 2000 Census recorded more than 6.8 million multiracial Americans. What will surprise Indian Americans, however, is that they at the front of the ranks. According to the 2000 US census, 220,000 Indians – almost 12 percent of the total Indian population of 1.9 million – identified themselves as multiracial, i.e. they listed themselves as Indian and one other racial group, which is five times the national average of 2.4 percent. Nationwide, almost 2.5 percent of all Whites, 4.8 percent of Blacks and 14 percent of Asians identified themselvesas multiracial.

Almost 40,000 of the biracial Indians identified themselves with one other Asian category and another 120,000 with Whites. The rest were mostly African American or Hispanic Asian Indian Americans. Tellingly, interracial marriages are especially high among Indians who were born in this country or grew up here (i.e. came to the United States before age 13). Almost a third of this group is married to non-Indians – a rate that is three times that compared to their parents’ group, most of whom were married before they migrated or returned to India to be hitched. For many Indians national identity serves as both talisman and sword. Most come to America with the assumption that life in this new world will resemble that in the old world – only dollar-enhanced – and that their identity as Indians is indelible, written in stone. But in the vast melting pot that is America, their children are finding partners in the workplace and in college. Ten years ago, the prospect might have scared most Indians. An acquaintance recalls a Gujarati friend who averted his eyes while announcing his daughter’s marriage to a Caucasian. It was as if he were in mourning. Increasingly, Indian parents are resigning themselves to the shift. Some parents are even happy that their child has found a soulmate, even if outside the community, while others fret, although most come around atleast when the cute grandchildren arrives.

Saira Mohan, the beautiful supermodel, whose father is Indian and mother French-Irish-Canadian, has been splashed across the cover of Newsweek as “The Perfect Face.” An intriguing blend of ethnicities, hers is the face of a global world, where cultural and geographical boundaries are blurred. She says about her own cultural mix, “Although I’m not completely clear on what ethnicity that makes me, I love who I am inside.” According to Backstage magazine, talent agents, casting directors, and talent management firms are now receiving requests for actors who are “ethnically ambiguous,” of “mixed ethnicity,” or have a “global look,” especially for commercials, films, and television shows. There is a new interest and openness to going beyond labels. That was surely not happening when California-based film-maker David Rathod was growing up in the early 1950s. Son of an Indian father and a Caucasian mother, he was three when the family moved to India and 7 when his parents divorced. His mother and sister returned to America and he lived with his father in India, who went on to remarry an Indian woman. At the age of 14, Rathod came to Chicago to live with his mother and sister. It was a big culture shock for the Bombay native. “When I came to America, I was almost entirely Indian. We lived in this upper middle class suburb of Chicago and my school was 99 percent Caucasian. At that time in 1966, India was very, very far away. There were no Indian restaurants anywhere; there were certainly no Indians where I lived. Phone calls were very difficult. So it was a big separation; all my friends were left behind. Being so young, I didn’t realize the consequences of leaving and I thought I’d be back, but that didn’t happen.” “I remember very vividly I was very embarrassed by that, because as a teenager you don’t want to be the focus of attention,” he says. “I had to shake off those Indian things so that I could become a regular American, which I obviously am. What I missed was friends, the climate and the food, definitely. But as teenagers, you kind of roll with it and move on to your next thing.” His father Kantilal Rathod was a film-director in Bombay of new wave films and when David was in college he re-connected with him because of his own interest in making movies. In the 1970s he rediscovered his Indian roots, became close to his Indian family and even married a white American who was very much into India and spoke Hindi.

“My interracial background has really defined me – it’s made me what I am now,” says Rathod, who brings his Indian sensibilities to the mainstream work that he does with films. Today Rathod himself is the father of two children, Sonali, 16 and Kamran, 11. How do his kids see themselves? “They look totally American – they are only one quarter Indian. But they are definitely interested in India and it’s a part of their awareness. It’s interesting how India has become big. Today a biracial child wouldn’t have such a hard time. In California it’s almost a badge of honor or something. I think kids of any mixed race are accepted quite nicely.” Even his real name – Devendra – is considered hip now, thanks to the emergence of an alternative rock star Devendra Banhart who has nothing to do with India. Laughs Rathod, “When I meet Americans in their 20’s and tell them my name is Devendra, a light goes on! They say, ‘That’s cool!’ It’s funny. I’m 53 and my name has come back, in a different way – but in a meaningful way – to a small section of America.” Yes, life is surely easier for children growing up in intercultural households today. As America celebrates its multicultural identity, it is hard to imagine that anti-miscegenation laws barring interracial marriages were on the books in a third of states until as recently as 1967, when they were overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled: “Marriage is one of the ‘basic civil rights of man,’ fundamental to our very existence and survival…. To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State’s citizens of liberty without due process of law.” Indeed, Alabama did not repeal its law barring interracial marriage until 2000. Would she do anything differently when she had her own children? She says, “I think my parents did a great job raising us with both cultures – through the foods we ate at home, having a range of family friends from both cultures and especially taking us to India and the Philippines throughout our childhood to be with our relatives there and to see how and where they grew up. I don’t think I would do much different.”

Rohi Mirza Pandya and Rehana Mirza sisters, two New York based filmmakers whose heritage is Filipino and Pakistani. Says Rehana Mirza: “Being half Pakistani and half Filipina did pose its challenges growing up, but I think that would have happened to me anyways as I grew up in a suburb where people of color in my school can be counted on one hand. I didn’t really think much about it during high school and college, but in my twenties and now my thirties I have embraced both sides and being a ‘desipina’.” Since their mother converted to Islam, religion did not become an issue, and being Asian, both couple held similar values and beliefs. The best part of being bicultural? Says Mirza: “Family is the best part of both cultures and can also be the most difficult as with any family.” “I feel that kind of attitude happens a lot with people. They just want to know something simple, they want to reaffirm what they think they already know. I remember I had to fill out a police report and the officer asked me what race I was, to put on the report. I told him half Pakistani and half Filipino. He looked terribly confused and asked if it was all right if he just put down Indian.

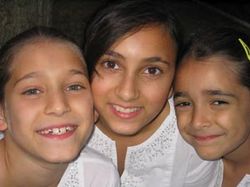

Pandya recalls the language barriers in the family, noting that everyone was surprised that English was the only language spoken in the household: ” I would always laugh at them and say how else would my parents be able to understand one another? It was always a humorous picture to imagine my Dad speaking in Urdu and my Mom answering in Tagalog.” Humor aside, Rehana says the hardest part was explaining to people that she is much more than meets the eye: “I feel sad if I only claim my father’s heritage just because it’s what I look most like. It almost feels like I’m wiping out or putting a shadow on what my mom gave me, which is important as well.” What would she do differently with her own children? She says: “I think I would let them know it’s important to embrace what feels natural to you, and always know that who you are is what you choose to be, not what others make of you.” What others make of them is perhaps the single biggest issue inter-racial children grapple with. The concept is almost utopian – the erasing of manmade borders – but the world is still small-minded and prejudiced, the old world struggling to remain static and stationary, afraid of movement and change. Erika Surat Anderson, a California-based filmmaker who is of Danish and Indian origin, has made films about the identity struggles, including None of the Above and Turbans. She recalls the pain she would feel when looking at her white exterior people would fail to recognize just how Indian she felt on the inside. Her brother Pyare, on the other hand, was dark and had a very hard time in school. He changed his name to Peter, but people still saw an Indian boy with a name like Anderson. Anna Roy is married to a Caucasian, and has a son who’s 10 months old. Does she think color and race will become an issue? She says, “I don’t think color and race will ever not be an issue, at least not in my lifetime.” But she knows there is a special joy in being biracial as these children can define themselves in any way they choose, without any cultural or social baggage attached to them. Nisha Kutty, a noted Indian fashion and beauty photographer, mother of a biracial child, four-year-old Surya, with her African American husband Al-Khadir Richman: “In India, we have so many different complexions and features within the community that it’s all encompassing. Over here there’s a huge, huge gap between Indians and African Americans. Here Surya would obviously associate herself with black people more, and disassociate herself with Indians more.” The roulette wheel of DNA spins to its own music and can create challenges as siblings end up looking so different. Ameena Meer, the author of Bombay Talkie has been married twice, both times to British men. Now divorced, she lives with her three daughters, Sasha Iman Douglas, 12, Zarina Elizabeth Nares, 10, and Jahanara Nathalie Nares, 6.

“All my daughters have very Indian features,” she says. “but two have dark hair and brown eyes and the middle one is blond and blue-eyed. When she was smaller she used to say I didn’t love her as much and that was why I made her blond. And, of course, her older sister took immediate advantage of the insecurity to tell her she was adopted!” Once upstate at a Sam’s Club, Ameena left her in the shopping cart in front of a woman handing out samples of frozen samosas. When she returned, blond 5 year-old Zarina was chatting away with an American trucker-type guy. He was saying, “Whoo-hoo, those samosas are spicy! Aren’t they too spicy, little girl?” “On United Nations day, the kids in the International School get to wear their national dress and carry their flag and my kids always make these very complicated flags, one side Indian, one side Union Jack and added to the top is an American flag, too,” recalls Meer. “Sasha varies between wearing desi stuff and Western, but my little blond is always sparkling in gota and sequins. Her complaint is that if there is a Muslim or Indian area of discussion in class, the teachers never think to include her amongst the desis or the Muslims. She often comes home feeling quite dejected, saying, ‘Nobody believes that I’m Indian. The teachers never pick me to answer questions.” In this saga of pigmentation, America is not color-blind. Nisha Kutty, a noted Indian fashion and beauty photographer, has heard all the stories since she’s involved in a biracial project, photographing women and their biracial children, primarily white mothers and their children with black men. “People can never believe it’s their child,” she says. “There are kids who have white moms and black dads and look just completely black. Apparently if you’re half black, you are just black in this country – they don’t consider your other ethnicity. There’s nothing like being half black – you are black.” Kutty became interested in the biracial project because she herself is the mother of a biracial child, four-year-old Surya, with her African American husband Al-Khadir Richman. “It was just interesting for me visually, just apart from all the sociological aspects of it,” says Kutty, who lives in Fort Greene in Brooklyn, where she says everyone seems to be of mixed ethnicity – half white or half black or other mixtures of something mixed with black. America is still so much about race – even though it likes to think it’s not – so will she face any special challenges bringing up Surya? Without blinking an eyelid, Kutty says, “Yes, definitely I will. I think if I had married someone white the whole story would have been different.” She feels the challenge might have been less if Surya grew up in India than it is here. “In India, we have so many different complexions and features within the community that it’s all encompassing,” she says. “Over here there’s a huge, huge gap between Indians and African Americans. Here Surya would obviously associate herself with black people more, and disassociate herself with Indians more.”

Prachi Patankar’s story is quite the opposite. The daughter of a Scandinavian sociologist and an Indian activist father, Prachi grew up in Kasegaon, near Bombay, a hotbed of activism where her grandparents were freedom fighters and her parents have always lived and been involved with issues like the rights of women, tribals and the building of dams. No one would suspect Patankar is part white because she looks completely Indian. “Many people are surprised when they find out I have a white mother,” says Patankar, who is currently a student at New York University, and a political activist herself. “Not that I have an issue with it, but I often wonder what goes through people’s minds and whether there’s something left unsaid or unstated in the reaction of people. But sometimes I feel it would be nice if my mom were kind of acknowledged. It’s not something that hurts me or anything – and I like the fact that I’m mixed and people are surprised.” Growing up in India, she found that people who knew she had a white mother always had different expectations of her than of an Indian girl. They were surprised that she spoke fluent Marathi, went to a Marathi medium school, and wore Indian clothes. Patankar had a harder time adjusting when she lived with her Scandinavian relatives in Minnesota for two years. She says, “Even after coming here I still view myself as someone who’s from India and who’s Indian. The white and Indian issue is not a big deal in terms of being a problem of identity.”

Maria Benjamin’s father is from Pakistan and her mother from Canada, who met when they were both training as nurses at Bangour Village Hospital outside Edinburgh in Scotland. Since her father is also Christian, religion has never been an issue for the children and the couple still live with their six children in Scotland. Maria, who is an artist and has now moved to London, says, “There was no real extended family to accentuate the cultural differences. My dad had to learn how to cook, as he preferred curry to my mum’s cooking. I love my dad’s curry, but I realized his limitations when I met his sisters and they cooked for me. But no one beats his specialty breakfast; a thick paratha with a fried egg on top.” Growing up in Scotland, color was an issue for the family and she feels things could have been very different if they had been brought up somewhere like London, where many different cultures live in such close proximity that mixing becomes a natural and accepted part of life. “In Scotland, in the small towns we grew up in there was a lot of racism. We moved to Edinburgh in 1984 where the racism was not so rife.” The best part about being of mixed race, she says, is that people can’t quite place her: “People have asked me if I’m Spanish, Italian, Mexican, South American, Aborigine, the list goes on, but no one ever thinks I’m Scottish till I open my mouth! I get a bit sick of having to explain my background when people probe my mismatching looks and accent, especially in the country I call home. To have people probe and doubt my sincerity when I tell them I am Scottish can be upsetting, because I feel there is a suggestion that I’m hiding something.” Since neither of her parents pushed their cultures on her, she views herself as Scottish. “It’s growing up in the countryside, appreciating nature, a particular type of understated humor,” she says. “The love of my Pakistani heritage seems more touristy to me. I haven’t got a clue about the subtleties. I remember one of my aunties giving me a beautiful salwar kameez to wear to a party and it was only years later that one of my cousins told me that they all felt sorry for me, because I looked so unfashionable. It didn’t even cross my mind that there was a fashion code!” As intercultural marriages grow, biracial children are part explorer, part philosopher, part negotiator, treading where no one has gone before and putting into action what are platitudes for most people – peace, harmony and oneness within diversity. As Saira Mohan says, “We are all human at the end of the day and we all have the same emotions. We come from the same place, regardless of culture, religion, color, skin, whatever. So those are the things I focus on and those are the things I like to build upon.” Ask David Rathod whom he sees when he looks in the mirror and he responds: “I have to say I see just me. But there are many times I see myself as Indian American, and there are times when I see myself as just Indian. And at times I’m just American and I think that is a growing story for children of interracial marriages.” Ask Rehana Mirza the same question, and she says, “When I look in the mirror, I see someone who has been made stronger by misidentification. I have had to struggle to see myself for who I am. I started to realize that bi-culturalism is a culture all of its own, so in some ways, I have four cultures to live with. Those of my parents, that of my surrounding community, and that which I embrace for myself.”

|

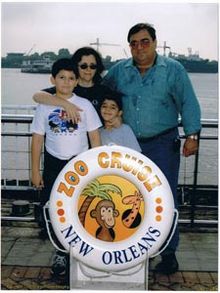

Yet ask Simon, who looks more Hispanic than Indian, and he says he respects both his ethnicities, but is frustrated because he can’t communicate with the Hispanic side of the family and his many friends who speak Spanish. In family gatherings he feels left out of conversations, since his father’s side doesn’t speak any English. Now in school he’s studying Spanish and is trying to balance both his ethnicities.

Yet ask Simon, who looks more Hispanic than Indian, and he says he respects both his ethnicities, but is frustrated because he can’t communicate with the Hispanic side of the family and his many friends who speak Spanish. In family gatherings he feels left out of conversations, since his father’s side doesn’t speak any English. Now in school he’s studying Spanish and is trying to balance both his ethnicities.