Arts

Tabla Meets Jazz

Indian classical music, a genre of South Asian music with two major traditions — Hindustani and Carnatic — began receiving interest in the West in the 1960s during the counter culture movement.

The Baruahs, based in Bethesda, Maryland, have always been a musically inclined family. Deeply interested in both Indian as well as Western forms of music, their two teenaged boys have been learning jazz and the trumpet. But when the family decided to attend a genre-bending concert held in Washington D.C. this spring, performed by renowned tabla player Ustad Zakir Hussain and jazz bassist Dave Holland, they didn’t exactly know what to expect.

Says, Alpana Das Baruah, a business analyst with a local firm, “I had attended a Zakir Hussain tabla concert some 10 years ago, and we have been attending jazz concerts for a few years ever since my older son began learning it. But we could never imagine the world of musical possibilities with tabla and jazz brought together.”

Das Baruah, who attended the concert with her husband and friends: “For me, the concert opened a new musical appreciation. I am today, more than interested in world music and the coming together of classical musical styles with various contrasting genres. The fact that the musical performance got multiple standing ovations and audiences were left both moved and mesmerized proved that the new genre bending style of music has many takers today.”

Indian classical music, a genre of South Asian music with two major traditions — Hindustani and Carnatic — began receiving interest in the West in the 1960s during the counter culture movement. As strains of Pandit Ravi Shankar’s sitar melded with George Harrison’s pop music, it gave the world a new form of music. Fusion became an alternate music trend and khyal and Western music were often intermingled for connoisseurs.

Zakir Hussain’s tabla came together with John McLaughlin’s guitar and Yehudi Menuhin invited sarod player Ali Akbar Khan to the United States. As East meets West form of music gained ground it also simultaneously found an influence in both the hippie and the yoga movement of the times. But as these Western collaborations with virtuoso artists from India evolved something strange happened.

The music, though admittedly enthralling, found a patronage mostly with the seasoned music aficionados. The music found a niche, albeit a narrow one.

But as a new generation of Indian music lovers move beyond Bollywood and pine to learn more about their roots and musical traditions, a new zing is being experienced in world music today. Young Indian classical musicians are influencing the world music scene and Western jazz and bass artists are increasingly looking to the ragas and the talas for a medley that speaks a universal language.

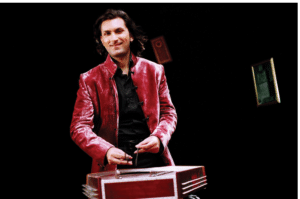

Rahul Sharma

Indian classical santoor player Rahul Sharma, who is equally popular in classical as well as fusion and world music, says that he is observing this new bent toward genre-bending classical music. Sharma worked with saxophonist Kenny G in his album Namastey India and with pianist Richard Clayderman.

He says, “While classical music has been blending with Western for a long time now, this genre was not given center stage and wasn’t marketed well enough for people to notice.”

Sharma, who is currently working on a new-age chill out album with EDM musician Marc JB from the United Kingdom, adds: “In the past years specific genres have come up and music labels became more progressive in categorizing music. World music has come into prominence and Indian music is a big part of this family.”

The genre-bending classical music is also introducing new dimensions to the world music map. Indian sitar player Fateh Ali Khan who played the instrument at Lady Gaga’s first concert in India a few years ago, says he is constantly seeing classical artists engage in newer dialogues, which are being appreciated by a new generation of music lovers.

Khan, who collaborated with Japanese artists in a project with the Japan Foundation to stage a romantic tale with Indian musical collaborations, says: “So, overcoming language barriers we created background music for Japanese dances adding shringar ras and classical ragas, such as raga jhinjhoti and raag yaman. The group is now off to Tokyo to present their classical Indian meets Japanese dance presentation.”

Khan says, “During all our collaborations, we ensure that we are putting Western music into classical music and not vice versa.”

Contemporary Classical Music

As new-gen classical artists make their mark on the music scene, their greater willingness to not be constrained by specific genres has helped in expanding world music. Recently, Pavithra Chari, a Hindustani classical vocalist, and Anindo Bose, a keyboard player and music producer, performed at 15 shows across the east and west coast as part of their Shadow and Light Tour. As visiting artists for the Berklee Indian Ensemble in Boston, their music ranged from classical, folk, semi classical to global influences of pop, rock, funk and jazz.

Describing themselves as a contemporary classical project from India, the duo insist that when they write music they do not pay attention to the genre. Chari says: “As a duo, we both (Anindo and Pavithra) come from very different musical backgrounds. Our influences are varied (Pavithra’s — Hindustani classical, Carnatic classical, Soul, R&B), (Anindo’s —classic rock, jazz and pop). When we write music together we don’t pay serious attention to which genre we are contributing to the piece as long as it flows into our songwriting process. What we create as a result of this, can be termed ‘contemporary classical music.’”

Bose adds: “For instance, in our third album, the vocals are deeply rooted in Indian classical music, while the arrangement is heavily inspired by R&B and jazz. Although it’s not a new genre, we would like to think that it’s the perfect reflection of contemporary Indian music today.”

Sharing the same sentiment is table virtuoso Aditya Kalyanpur. The child artist in the famous Indian Wah Taj TV commercial in India, Kalyanpur is today an established tabla player who has performed with Ustad Amjad Ali Khan, Pandit Shivkumar Sharma and also collaborated with Grammy winner John Pepper and Keith Richards. During his American concerts, earlier this year, he said that he is as open to popular music as he is to classical, “Music is a universal language and I do not distinguish between genres.”

The Real Fusion

Young classical artist Murad Ali, who belongs to the sixth generation of sarangi players from India, is a part of Rebel Deewana, a band spearheaded by famous French composer and improviser Titi Robin. While Khan is on the acoustics with sarangi, Robin plays electronic guitar and the group’s music is interspersed with French poetry.

Murad Ali: “While classical music has been blending with Western for a long time now, this genre was not given center stage and wasn’t marketed well enough for people to notice.”

Ali says: “There is definitely less apprehension amongst the new classical artists to try and include music from other genres.” However, he cautions: “Fusion music is also a greatly misused term today. It is important to sieve through a real collaboration from playing fusion just as a fad.”

Ali who has lent background music in Hollywood movies, such as East is East and The Forest, explains why fusion got a bad rap: “A host of younger classical musicians were eager to be heard. But since the stalwarts continue to hold the baton of Indian classical, often getting a break becomes a challenge for a new artist. Given a still lukewarm interest of the masses towards classical music, many musicians resort to popular even gimmicky fusion just to get by.”

Indian sufi singer Zila Khan who recently performed and sang in Gauhar, a play staged at New York City’s Lincoln Center, insists that world music today is as rich as the tradition of Indian classical music, says: “We are talking about real fusion and not the fusion as people would simply understand. Indian classical is gaining grounds in world music platforms only because there is a structured collaboration. There is a form, a discipline and essence of different genres woven together to make a musical carpet. I have also seen horrible music concerts which can scarcely be defined as taking Indian music ahead.”

Murad Ali concurs: “The real genre bending music is where the classical ragas are never tampered with. For instance, if we are singing raag yaman, the sur remains the same. The various genres are made to enhance, not confuse our classical symphonies.”

Zila Khan offers an example: “When I am on stage, singing a kalaam by Hazrat Ali Khusrau or by Rumi, the traditional andaz remains the same. It only acquires a different world flavor.”

Most artists maintain that this unique flavoring adds a whole new repertoire to classical India music and attracts new listeners.

Anindo Bose says: “Every artist interprets genres in their own way and that also keeps evolving with time as the cultural influences change. We have our own way of blending our influences rather than putting them under different categories or labels. There’s more focus on song writing now as opposed to long improvised pieces of music which were very prevalent in the past. There’s more variety in the way people fuse music. There is a huge difference in the production value of the recordings and the kind of instrumentation used by artists that makes for a very enjoyable listening experience. Artists are also inspired by different performance and visual art forms in their pieces.”

Digital Proximity

Another reason classical music is seeing a contemporary revival is because digital platforms have opened up a new music space where the availability of every genre and instrument is only a click away.

Zila Khan recalls his talk earlier this year at the Google office in Sunnyvale: “I sang a bandish of my great grandfather Ustad Imdad Khan and I said that for me the biggest ustadgah or gurukul is this digital technology, because today for lovers of music, the same bandish recorded back in 1902 is readily available on YouTube.”

Pavithra Chari agrees that newer digital platforms are changing the musical landscape: “Artists now are finding inventive and unique ways to involve social media and the internet in their creations, and that is interesting to observe. Connectivity and reaching out to people in different countries or continents is also much easier now.”

As more people access different genres of music, they discover the many similarities between instruments and acoustics. Rahul Sharma offers an example: “The santoor is a unique instrument as it has 100 strings and was originally called the shatatantri veena which means an instrument with 100 strings in Sanskrit. Originally belonging to Kashmir, my father and guru Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma gave it that stature of classical music.

“But the santoor is also found in different countries known by different names such as Yang Chin in China, santoori in Greece and hammered dulcimer in America. It probably travelled with the gypsies to Romania and western Europe.”

He adds, “Indian instrumental music is a huge part of the global world music and today no festival is complete around the world without an Indian sound.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login