Arts

Shades of Grey

Review of the Indian Film Festival in Los Angeles?

Film festivals have become major spectacles of our times. They affect the business, culture and commerce of films. As central occasions to embrace cinema, they thrive on the hunger of cinema-lovers to nurture their tastes and passion for films. By some accounts, there are 7,000 film festivals around the world, in virtually every corner, from Bedouin tents to the glossy beaches of the French Riviera, from your own neighborhood to major cities on all continents.

The festivals influence the shaping of cultural identities, well beyond their role in forging connections between the filmmaking, marketing and finance communities. To some, that function of community building is as much a mirage as the goal of nurturing the love of cinema is overshadowed by the crass commercialism that parades at these spectacles. And yet, as major global phenomenon film festivals serve many functions: they shape how communities come together, how they reassert themselves and how they connect to their own heritage. For communities in diaspora, those attempting to find home away from home, film festivals offer spaces, opportunities for revelry, patronage of their own artists and moments of communion. This function is not unlike that served by religious or traditional festivals, which remind us who we are even in the midst of a life that rarely connects to traditional elements. Thus, in India, a film festival in Kerala celebrates films from around the world, but it also brings together the local film crowd in the name of cinema. There are film festivals in New Delhi and Mumbai, but also in Gauhati and Kanpur. Nearly every IIT (Indian Institute of Technology) has a cultural festival in which films play a major part.

Outside India, much like other diasporic communities around the world, we have film festivals in New York, Houston, Chicago, Los Angeles, etc. dedicated to films from India. This ought to be a curious development. How in the age of the cheap DVDs available in grocery stores, the large repertoire of Indian films at Netflix, the ease of online streaming services and cable/satellite channels, can we still have film festivals that prompt us to get out of our homes and onto the streets for a couple of dozen films in the midst of a work week? The Indian Film Festival of Los Angeles (IFFLA), held from April 12-17, in Hollywood, just a few blocks from the tourist attractions of the Kodak Theater and the walk of fame had all the trimmings of film festivals — the red carpet, award, etc. It featured films you are not likely to find in your neighborhood Indian grocery store. That is the first distinguishing feature of this festival. Bollywood cinema did not figure into the festival, except in a strategic way. There was plentiful of it outside the event. A festival of Bollywood films would mean a lot less in this already crowded world of that cinema. For the most part, IFFLA is about independent cinema.

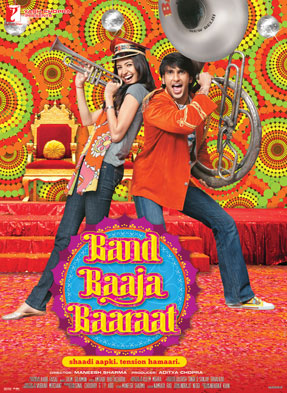

This commitment to cinema that is different from the usual fare is a strategic contribution this film festival makes to our understanding of ourselves. Programming is at the heart of the identity of a film festival. Here, the programmers, six of them, each assigned to a separate category, from shorts to documentary to feature films, provide a direction to the festival that appears to be a strategic compromise between the need to highlight talented works outside the mainstream — “India-centric” films produced by North American as well as diasporic filmmakers — and the desire to attract a broader audience to what has become a major event for the Indian community on the West Coast. Thus, there is Bollywood by Night, a series of screenings late at night, past 9 p.m., showcasing the recent favorites from the native film making industry that has become a global phenomenon. Rajnikanth’s megabuster Robot/Endhiran festival had attendees wait in long lines and forced the organizers to add extra screenings. Kiran Rao-Amir Khan’s Dhobi Ghat/Mumbai Diaries and Maneesh Sharma’s Band Baaja Baaraat/The Wedding Planner in the Bollywood by Night program brought out second generation Indians, who also made a party out of the night. Two very rich programs of short films showcased a diverse selection of films from India, film students in the U.S., as well as filmmakers from Pakistan and Canada. The broad palette suggested that programming is a strategy rather than a clear commitment to themes.

The festival was a stage for remarkable documentary works: Phil Cox’s The Bengali Detective, Sonali Gulati’s I Am, Sweta Vohra’s Pink Chaddis, Kim Longinotto’s Pink Saris, Srinivas Krishna’s Ganesh Boy Wonder and Bill Bowles and Kenny Meehan’s Big in Bollywood. Together, the films demonstrated a mature growth of the documentary form. The festival’s core focus was represented by films like Murali Nair’s Laadli Laila (Virgin Goat), Anurag Kashyap’s That Girl in Yellow Boots, Aparna Sen’s An Unfinished Letter, Nila Madhab Panda’s I Am Kalam, Vikramaditya Motwane’s Udaan and Onir’s I Am. By the time the final screening of Disney’s Zokkomon arrived, the festival had captured the diversity of the overseas Indian community, reflecting its abiding interest in knowing more about India, while exploring the talents, background and the realities back home and here. Christina Marouda, executive director and the founder of IFFLA, said in an interview that the intent of the festival was to provide exposure to films “that needed a platform.” Marouda sees this festival as establishing its own “niche,” and broadening its appeal in the South Asian community. Indeed, the program included a perceptive and thoughtful short film by a Pakistani filmmaker, Iram Parveen Bilal, titled Poshak/Façade that captured the search of the inner self in the midst of a culture that demanded everything from an artist.

IFFLA, which Marouda claims is the “premier” Indian film festival in the U.S., maintains a strongly cosmopolitan outlook with feet firmly grounded in films from and about India. Marouda herself is a Greek immigrant, arriving in this country some 11 years ago, steering this festival for the past nine years. The other organizers of the festival are a multi-cultural bunch too; revealing how the centrality of the Indian films is nurtured and promoted by others in one of the major cities in the U.S. Marouda said the festival received nearly 400 film submissions this year, of which just 30 were included in the program. She said the festival gives “confidence that there is good quality film making in India,” the audience looks forward to the event each year and is “aided by a community-family of organizers” that is passionate about its mission. The festival’s deft programming and strategies marks it as an event that is situated in one world while speaking for many. Indian Americans aren’t all wedded to Bollywood and neither is India all about Bollywood. The diasporic community of Indians has been a vibrant component of world cinema. From Mira Nair to Gurinder Chadha and Deepa Mehta, there is a sizeable body of work by filmmakers outside of India, with their roots firmly in their home culture and their intersections with other cultures. It is by now a truism to say that there isn’t just one image of India (shining or otherwise!), but multiple images. We don’t know of any other diaspora as vibrant in cinema. In addition, Indian culture continues to form the center of artistic, cultural and political concern of filmmakers, diasporic or otherwise. IFFLA is a testimony that the community hungers for filmmakers outside Bollywood, despite all the glamor and money the industry attracts.

The audience for the event included the party-crowd that headed for frankies, dosas and biryanis from the trucks parked on Sunset Boulevard in the evenings. There is something about eating a heavy meal at that late hour, particularly outside the movie theater, that ought to remind one of home. The festival organizers kept alive a loyalty through Twitter and Facebook, with posts and updates about goings-about and last minute recommendations and impulses. A soundstage outside the theater kept the hum on music and dance. Inside, stars like Gulshan Grover and Anupam Kher hobnobbed with up and coming filmmakers. For the media and for the stars themselves, there is the red carpet on the opening and closing nights. An event on this scale and of this nature is always a mixed bag. One of the common laments in festival circles is that these festivals rarely focus on the filmgoer. Instead, the festivals have become marketing and finance extravaganzas and platforms to launch films. For an “ethnic” film festival held in the filmmaking capital of the world, it is hard to resist these temptations.

Executive Director Marouda said that IFFLA has launched a film fund to “discover” and support talent with funding for their projects. It isn’t clear if this will instill a certain aesthetic that is diasporic or committed to the concerns of the community abroad. Many of the directors were introduced as “alumni” of IFFLA (Vikramaditya Motwane — Udaan and Geeta Malik — Troublemaker). If 400 filmmakers knocked on IFFLA’s door, it is clear that the choice in programming influenced the kind of films accepted here. The community needs to see this as a sign of possibilities to support good cinema that is not all song and dance and fights and bloody or sexual fantasies. The divide between the sensible or good cinema — the kind supported by film festivals and mainstream cinema — couldn’t be clearer in an encounter during a seminar organized as part of the event. Gulshan Grover, star of many Bollywood films and now in Nila Madhab Panda’s I Am Kalam, rose from the audience to ask questions of panelists that included Abhay Kumar, Nisha Ganatra and Vikramaditya Motwane. While Grover didn’t forget to emphasize his “generosity” in supporting an “alternative” film like I Am Kalam, he asked if the independent filmmakers always dream of casting a famous star in their films. His other question went further. He suggested, nonchalantly, that independent filmmakers usually have only one film in them and then burn out.

It is hard to read the minds of the filmmakers who work by raising their own funds and making their own way in the industry. The panelists, successful and brilliant in their own work, seemed hesitant to answer his questions. It was an instructive moment. It is alarming that those who have found a way to make money in mainstream cinema harbor some distaste for art that does not correspond to their own and that good work must be pursued without much support for hiring scriptwriters or cinematographers, let alone publicity machinery to promote their films. They are not looking for glamor, because that isn’t the end for the creative world. They may have more in them, but they get exhausted begging and struggling for a place in a noisy world of ruthless competition. The questions reflect, unwittingly or otherwise, a filter through which the mainstream film industry looks at filmmakers who make meaningful films, pitifully and patronizingly at the same time. The final closing night featured a world premier of Zokkomon, a live-action Disney production that boasts the first superhero based in India. The film is about to be released in India and IFFLA was the prime venue to introduce it to the overseas Indian audience. Needless to say, the house was packed for the screening. The movie features a child superhero who acquires powers that are a cross between Iron Man and Batman, mentored by a wizard with a revenge to settle against a local bad man. The film opens in a Disney-like amusement park, with a song-and-dance routine that demonstrated how perfect the marriage between Bollywood and Hollywood has become. It was hard to discern they were two different, separate worlds.

The film offers villains and side characters that belong to both soils at the same time, blending one into another. There’s that kicking-the-behind capacity of the superhero and the swift, dramatic resolution of evil deeds to assure us that we are watching a symbiosis of the two worlds. But that was the least disturbing feature of the evening and the film will no doubt do very well. The alarming aspect came in the introductory remarks by Jason Reed, executive vice president and general manager of Walt Disney Studios International Productions who announced that Disney would soon launch a new brand this summer called Disney World Cinema. Of course, Disney will do what Disney does best. But the idea that Disney will now produce films from around the world, reproducing heroes and formulas that have been established in the West and then market their own stories to people of different cultures is abnormal. No one can accuse Disney of being subtle. But the ease with which we subscribe to this idea and take pride in the claim that we are the first in making a native-planted superhero suggests that we have become so drunk by the attractions of the marketplace that native voices, independent expressions are likely to be drowned further by this coming juggernaut. The very term “Disney World Cinema” was chilling enough to warn us that cinema is about to go the same way as “world music,” catering and molding to the taste of the large markets in the West, suffocating original and native voices. It is hard to overstate the glee in Anupam Kher’s presence after the screening (he performs a dual role in the film, the hero’s mentor and the bad guy — the uncle of the child who becomes Zokkomon). It was equally hard to observe the wave of disappointment, one would guess, in the hearts of the many filmmakers in the audience, who had made meaningful films with such struggle.

|

You must be logged in to post a comment Login