Twelve year-old Sehej Ahluwalia ran a half marathon in the Bay Area in October to raise $1,000 for Pratham. 16-year-old Sejal Dave organized a fundraiser in New Jersey in 2001 that raised $40,000 for the Sankara Eye Foundation. Dave, who went on to a masters in public health, is now working on a documentary on Sankara. Gita Narsimhan, a New Jersey college professor who has lived in the United States for 30 years returns to India periodically to volunteer for Lend-A-Hand India and is documenting the work of Vanasthali, which has set up 3,290 nursery schools in Maharashtra helping thousands of children.

|

|

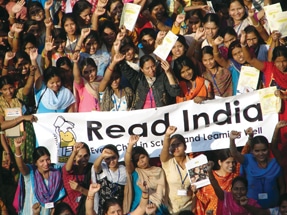

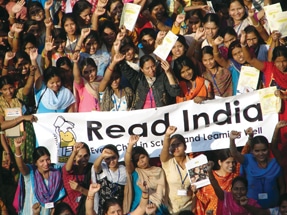

Pratham team in India celebrates its success at the Read India mela in Nagpur. |

Indians may not have a reputation for philanthropy beyond religious or local causes, but growing numbers of overseas Indians are beginning to step up to the plate, contributing their services and money for education, poverty, healthcare, and other social services in India.

Now Indians are catching up. Weve seen a huge ramp-up in fund-raising activities the last one year or so, says Leona Christy, program director for Pratham USA. Pratham tackles illiteracy in India with programs like Read India, which, it claims, reached over 34 million children in India in 2008-09.

What has prompted Indian Americans to open up their heart and purse strings? Economic security for one. Indian Americans are among the most affluent ethnic groups in the United States and are striving for an identity. Indians in America are lost between being American and Indian. They are in a flux. This drives them to go beyond barriers and identify within themselves, says Gomathi Swami, a volunteer at Isha Foundation, which conducts yoga sessions across the United States, the proceeds of which are donated to social programs like Isha Vidhya, Project Green Hands and Action for Rural Rejuvenation.

The more financially secure are feeling an urge to give back to their country of origin. Alok Bathija, publicity coordinator for the New York-New Jersey chapter for Asha for Education says, Most Indians in the U.S. want to give back to the country they love. Through its 45 U.S. chapters, Asha for Education raises funds for its programs to educate underprivileged children in India. Asha has raised $4 million since its inception in 1991 to support 385 projects in 24 Indian states.

Indians, who have the highest educational attainment among all groups in the United States, are especially partial to educational philanthropy. Aside from Asha for Education, Pratham, which provides remedial education to children in Indian villages, and Ekal Vidyalaya Foundation, which focuses on educating children in the tribal areas of India, are beneficiaries of their largesse. Says Parthams Christy: Indians are successful as an immigrant community due to their educational background. They identify education as a ticket to a better future. Due to this they see education as the best investment in a social cause. Pratham has 10,000 individual donors who have contributed over $10 million over the years and 300 active volunteers around the United States.

|

| Seva eye camp |

Organizations that provide health services are also a big draw among overseas Indians, perhaps none more so than the Sankara Eye Foundation, which offers 70,000 free eye surgeries annually at its hospitals, eye banks and eye care programs. Sankara services the 15 million blind people in India, contending that 80 percent of blindness is preventable. Since its U.S. inception in 1998, Sankara has seen Indian American involvement double every three years and it presently boasts 35,000 individual donors and 700 volunteers in the United States. Blindness is also the focus of the Seva Foundation, whose Seva Sight Program proposes to make cataract surgery as ubiquitous as McDonalds. Over the past 30 years, Seva claims to have helped restore sight to over 2 million people worldwide, the majority in India and Asia.

In the past, many Indian Americans were apprehensive about supporting Indian nonprofits, both because they didnt trust their integrity and also because the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA) made contributing cumbersome and costly. In recent years, the government has relaxed and streamlined rules governing contributions to Indian charities and Indian nonprofits have become more professional and transparent in their operations.

Christy says, Indians have realized that NGOs (non government organizations) do great work. At the same time Indian NGOs have also become more professional and market savvy.

Sankara targets repeat donors by facilitating a sense of ownership amongst its volunteers and donors. It regularly sends donors certificates for every eye surgery their contribution supports, which helps donors see their impact. Seva Foundation runs a Gifts of Service program in the U.S., which helps to introduce communities to Seva.

|

| A Share & Care Foundation physician treating a child. |

Aaron Simon, program communications manager at Seva Foundation, explains: Gifts of Service is an alternative gift giving program run by Seva that allows donors to honor friends and family by sponsoring a project in India or throughout the developing world. Gifts of Service that are popular with the Indian community in the U.S. include Restore Sight to a Blind Person in India, and Train a Local Health Worker in India. A beautiful card is sent to the person the donor is honoring. Many of the gift recipients are so moved that they in turn give them the next time they need to give a gift to someone.

Nonprofits are tapping not just the money, but also the expertise of Indian professionals. Sunanda Mane, president of Lend-A-Hand India, says, LAHI attracts volunteers from diverse backgrounds. 30% are India born, 30% are Indian Americans and about 40% are Americans, which also includes a very small percentage of other nationalities. LAHI is a small nonprofit that collaborates with dynamic grassroot nonprofits in India to provide vocational training, career development, employment, and entrepreneurial opportunities to young boys and girls in rural and urban communities.

Mane says: The group which is involved in volunteering with LAHI consists of young professionals. Besides the desire to give back to the community, personal goals such as opportunity to network, learn new skills such as event management and leadership, act as motivating factors.

Prathams Christy also sees encouraging signs of involvement among younger professionals. She says: Indians in the U.S. have evolved more in terms of learning from American culture of giving to non-profits at a young age. NRI parents are motivated to get their children involved with Indian causes and through that they feel their children will be closer to and learn more about India.

Most nonprofits rely on word-of-mouth and low cost campaigns, such as banner exchanges and emails to generate support. Others, such as Seva, have invested in branding their identity. Says Sevas Aaron Simon: Our Sanskrit name, Seva, and our logo the eyes of the Buddha are both familiar to Indians and catch their eye when they spot us at events and when flipping through publications. Working at Seva information booths at events we often have people come up to us, explaining that they saw our logo from far and made their way over to find out what our organization was all about. When they learn of our mission and Sevas programs in India they often request more information.

The volunteer base of Indian nonprofits in the United States has grown tremendously in recent years. Sankara, which started with three volunteers in 1998, now has 728. Pratham says five to six volunteers sign up online every week. Volunteers organize fundraisers, help with administrative work, run local chapters and act as ambassadors for their organizations.

Some provide highly specialized and professional expertise. Seva, for instance, relies heavily on volunteer doctors, according to Simon: We have many Indian doctors living here in the U.S. who volunteer to go abroad and work to support our programs serving the poor. Many provide direct services such as restoring eyesight to the poorest of the poor who cannot afford cataract surgery. Others volunteer to do health trainings like training doctors and assistants or adapting new techniques. Those who do not have time to volunteer abroad, choose to help out at Sevas headquarters in Berkeley, California stuffing envelopes or answering phones.

Some volunteers work full-time, others are retirees. Sankaras Murali Krishnamurthy quit his full-time job as a software engineer to volunteer 15 to 18 hour days for Sankara. According to Arun Bhansali, Share and Care Foundation (SCF) has 40 volunteers who gave consistently 400 hours every year for last 27 years. Their current earning power in their profession is average $75 per hour.

Volunteers are often overwhelmed by the impact of their work. Bhansali relates how a team of NRI physicians returned to a SCF medical camp in Rajkot to see that the malnourished and unkempt children they had treated a year earlier were now thriving. The physicians got such a heart-warming reception from the children, most of who had never seen a physician before, that they signed up to return the next year at their own cost.

|

| Sankara eye camp. |

Indian nonprofits are increasingly adopting mainstream fundraising tools, such as marathons and auctions. Some donors have requested guests attending a family wedding or birthday party to donate to their favorite charitable cause in lieu of gifts. Sankaras Krishnamurthy relates a touching story of a retiree who donated virually all his savings to the organization. One day Swami Satyanand Bharati walked into our office. He asked if anyone could speak in Gujarati. I said I could help him in my broken Hindi. He said he saw ours ads in a newspaper and initially wanted to donate $4,000 to Anand hospital. Then he changed his mind when he read about four of our hospitals and he wanted to donate to all of them. The 81-year-old man wept as he left the office, saying he had donated all the social security money hed saved and was happy that he had donated for a good cause.

Indian nonprofits are also becoming increasingly savvy about tapping corporations and foundations for support. SCF secured a $500,000 grant from Lucent and nearly $500,000 in medical equipment and supplies from several hospitals and physicians, which has allowed it to invest $58 million in 850 programs with nearly 500 Indian nonprofits over the past several decades.

Nearly 200 Cisco employees donate to Sankara and their donations are matched by the company dollar for dollar. Prathams Seattle chapter has a deal with Microsoft under which the company makes a contribution to Pratham for every hour a Microsoft employee volunteers with the organization. Pratham has also received $9 million over three years from 2007-2009 from Hewlett Packard in partnership with the Gates Foundation as well as from the philanthropic arm of Google.

|

| Volunteers participating in New York Marathon to support Lend-A-Hand India |

As the volunteer and donor base ratchets up, the nonprofits are discovering the need for developing stronger and regular communication channels, such as newsletters and e-mailers. Lend-A-Hands Mane says, It involves staying in constant touch and following up to keep volunteers motivated. Asha volunteers stay connected via e-mail, chat sessions and regular conference calls, according to Alok Bathija: Even without knowing many of our team members personally and professionally we work hand in hand towards the continuous growth and development of the organization. We have a bi-annual conference which allows volunteers to put a face to the e-mail ids with whom we communicate. Isha Foundation organizes satsangs every month and volunteers participate in advanced yoga programs in Tennessee.

The overwhelming thrust of Indian American philanthropy has long been, and continues to be, directed at India. However as the community population grows and a new generation steps into the public sphere, Indian Americans are also turning to local causes.

Organizations such as Sakhi and Manavi serve domestic violence victims in the South Asian community; SAYA (South Asian Youth Action) promotes social change and opportunities for South Asian youth; South Asian Americans Leading Together (SAALT) fosters civic and political participation among South Asians. This new focus in Indian American civic participation is highlighted by the 40,000 sq. ft. India Community Center (ICC) in Milpitas, Calif., which offers a wide range of social, cultural, recreational and community programs. Established only in 2003, the ICC has risen rapidly to become one of the largest Indian nonprofit organizations in the country, with assets exceeding $20 million.

Navigating and balancing the competing needs of its own community in the United States against the crucial lifeline that overseas Indian financial support provides to causes for the poor, women and children in India may well be the biggest challenge facing the Indian philanthropic community in the years ahead.

|