Magazine

Prisoners Of Race

I encounter bigotry and prejudice all too frequently among my Indian American family members.

| I encounter bigotry and prejudice all too frequently among my Indian American family members.

It’s a beautiful summer day in Palo Alto, Calif. My cousins and I rush to take our seats in the backyard of a house on the Stanford University campus. My aunt can’t stop laughing as her son’s funk band starts playing. She tells us, “I’ve never seen him like this.” Her son, my cousin, is jamming on his sax, wearing shorts, flip-flops and an Afro wig. At 6 feet 2 inches, he’s easily the tallest member of the band; he is also easily the darkest-skinned of the mostly White band. Over burgers and hot dogs after the concert, my aunt explains to us that my cousin was on a road trip in a convertible recently, which is why his skin is so tanned, as if his darkness is something that needs explanation. It reminded me of the time my mom related to me the remark of another aunt after I was born, “She’s so dark.” I was visiting San Jose for my sax-playing cousin’s graduation, a trip that included features typical of family gatherings in the U.S. – delight at seeing relatives I have not seen in weeks, months and sometimes even years; joy at being able to go back and forth between English and Kannada; the kind of laughter that is only possible with people who know you since you were a baby; and finally, bouts of nausea caused both by the blatantly racist comments of relatives and my own inability to challenge them.

Though this particular trip lasted only three days, I encountered numerous examples of prejudices that I hear all too frequently among my Indian American family members. The first comment came as I discussed possible places for lunch. One cousin mentioned eating Chinese food recently in a part of town with numerous Chinese restaurants, noting, “I saw flies there and do you think it’s a coincidence it was in that part of the town?” I was stunned into silence. Then I thought, “Really? You think that?” But I said nothing. While I puzzled over what I should have said, we drove to a gas station to fill up before we headed to an Afghan restaurant we had finally settled on. As we chatted about the rising gas prices, my cousin said that she couldn’t understand why the gasoline price hike was such a big deal, “Surely an increase of 50 cents cannot be that much of a burden on someone’s budget.” Later when I learnt just how much she and her husband made at their IT jobs, I could understand why gas that topped $4.50/gallon was no “big deal” for her. On a graduate student stipend, I spend almost 30% of my annual income on rent, while my cousins, whose apartment costs three times as much, still spend only 12% of their income on rent. By the time I had made these calculations in my head, we were eating lunch and hurrying to get to my cousin’s funk band concert. Next it was graduation day at Stanford University. Some 20 family members attended the graduation in the university’s football stadium. It was a warm, sunny day. Most women, wearing short-sleeved shirts, ended up getting sun burned sitting through Oprah Winfrey’s long-winded speech. Later that night, I was commenting on my dramatic tan line when one cousin made some remark about Winfrey. My other cousins, uncles and aunts cracked up. I couldn’t quite hear what he said, but his wife responded, “You can say things like that in the house, but make sure you don’t say that outside.” One aunt cautioned that we should be careful about what we say, because her daughter does not like it when they use the word “Black.” I gathered that my cousin’s comment referred to Winfrey’s dark skin. This time, I said nothing since I had not heard the actual comment. Later that night, another cousin’s wedding album was passed around. My great aunt began disparaging the book’s cover photo, which had the cousin and her husband in casual clothes and pose. She said that the boy was so handsome, but you couldn’t tell that because of his beard. And that my cousin looked even worse – “she looks like a tribal. It’s a terrible photo. I don’t know why she picked this one to put on the cover.” There were murmurs of agreement. Yet again, though I was shocked by her choice of words and the vehemence with which she criticized the photo, I was silent. This time, I justified it by wanting to respect my elders and my inability to challenge her in Kannada.

Other photos were criticized that night. A cousin, a sophomore in college, had decided to grow a beard. The great aunt was thoroughly appalled. “Oh my god you look just like a Muslim. It’s terrible.” My cousin just laughed. His mom piped in to say that she has begged him to shave before he gets on a plane. There were more disapproving comments about how he looked Muslim from some of the other relatives. I’m sure by now, you can guess what I did. That’s right. I said nothing. The next day, there was a pooja (religious ceremony) for my uncle’s 60th birthday at a small temple, located in a garage-type building. I chuckled at the adaptations by the temple’s priests. The homa (fire) was created in a tinfoil container, to keep the carpets clean and making disposal easier at the end of the ceremony. As the priest instructed my uncle and aunt, he said to their daughter, “You should get married soon, because there are certain things that only wives can help their husbands with and there are age limits on that. I know everyone wants to get educated, but enough education now. You need to do other things.” My male cousin burst out laughing, teasing his sister loudly that she needed to listen to the priest. I rolled my eyes at the laughter that echoed in the room. Later during the pooja, the priest opined that we all need to make sure that we married Hindus. When some people gasped, he responded: “Well, it’s true. We did not move here just to make money, we need to continue our traditions.” What traditions would the priest have us continue to uphold? Discouraging young women from pursuing education? Devaluing, disparaging and dismissing those who look different or practice a different religion? Having a sense of superiority over those who have less power in society? As frustrated and infuriated as I was by these comments (and this weekend seemed to pack more of them than most family gatherings), I was even more frustrated by my own silence. This was not the first time I had heard prejudiced comments from my relatives against Blacks or Muslims. Nor was it the first time I had been exposed to their ignorance about what it means to be poor either here or in India. The priest was certainly not the first Indian I knew to make boldly sexist comments to good-natured laughter. And unfortunately, this was also not the first time I chose to be silent and thereby tacitly agree with such comments. I am fortunate that I rarely hear my parents make such blatantly prejudiced comments and when they do, I am comfortable challenging them. Recently, my brother, sister-in-law and I had a spirited conversation over Hillary Clinton’s appeal to the racist beliefs of White voters. However, when it comes to family members outside my immediate family, I find myself tongue-tied. I don’t know how to challenge such comments or at least to register my disagreement. The most I do to chip away at their attitudes is to share widely pictures of my social circle, which includes friends from a diverse array of racial and ethnic backgrounds.

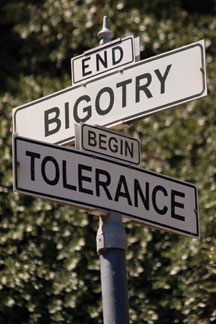

I can always come up with excuses for my silence. I feel insecure about my own standing within the family – I’m an unmarried 30-year-old woman, pursuing a PhD in Education (“Oh, that’s interesting.”) and have the shortest hair for a woman in my circle of relatives. I am unsure about how to go about challenging comments made in Kannada, because my Kannada is weak. And I cannot challenge the comments of uncles, aunts, grandfathers, great aunts, and so forth, because it would be perceived as being disrespectful. I am especially astounded that my relatives, most of whom are highly educated, can be so bigoted. I suppose I’ve become used to confronting and challenging the much more subtle – though no less devastating – racism that abounds in the halls of academia. Part of my inability to respond to my relatives’ comments stems from my disbelief that supposedly “educated” people could hold onto such stereotypes. But I want to start saying something, even at the risk of sounding preachy, politically correct, or just plain Pollyanna-ish. I want to do so partly because I am committed to opposing and teaching opposition to racism, but mostly because these comments disparage some of my closest friends who have been an incredible source of support, inspiration and love over the years. I want to tell my relatives that that difference isn’t so bad; in fact, it can be enriching and exciting. I write this as a starting point in that conversation, since I often find myself braver and bolder in writing than in speech. I do not believe that my relatives will necessarily change their minds after reading this. However, I do want to register, finally, my protest against their bigotry. |

You must be logged in to post a comment Login