Magazine

Outsized Dreams

These Indian Americans have larger than life ambitions.

|

Meet the Raja of a Ghost Town, the Cigar King, the Magic Carmaker and the Builder of Dreams. Sounds like characters out of a fairy tale? No, these are real life people, albeit with outsized, sky’s-the-limit ambitions.

Rocky Patel of Naples, Fl., can boast of something that probably no other Indian anywhere in the world can – he actually has a cigar named after him! Other Patels may be content with motels, newsstands and franchises, but this Patel owns huge tobacco plantations and his Indian Tabac Cigar Company has an avid following of cigar aficionados. Krishnan Suthanthiran of Springfield, Va., is the master of an entire township set in pristine British Columbia, laden with underground minerals and abundant wildlife. But he has no subjects – the buildings and homes lie vacant, the stores are empty. He is master of a ghost town, but with big plans to make it thrive again. Sankar Dasgupta of Missisauga, Canada, is looking to transform the gas-guzzling, environmentally incorrect world with a zero emissions electric car and has developed batteries that run laptops for 24 hours. In his vision we’ll be living in a cleaner, healthier, more efficient world and rid of our oil dependency. Real estate developer Arun Bhatia of New York has added to the jagged, glittering skyline of the Big Apple with a dozen skyscrapers in Manhattan, totaling millions and millions of dollars and concrete and glass, and providing state of the art homes to over 2,000 people.

All their stories began in India in remote villages and big cities, and their basic homegrown culture and values continue to shape their characters. And yet in all of them, Indian smarts and education have mingled with American risk taking and innovation to create their larger-than-life success stories. Rocky Patel (real name Rakesh) left Bombay when he was just 14 years old. He had probably never His company has grown into a $15 million business that produces 7 million cigars annually. You’ll find “Rocky Patels” in all the major restaurants from the Four Seasons to the Ritz Carlton to country clubs, hotels and retail shops in the United States, as well as many countries in Europe and Asia. The path Patel started out on was a traditional one for affluent Indian immigrant families; he decided to study law. A business and entertainment lawyer in Los Angeles, he built up a thriving 14-attorney practice.

“In the course of my work, I found myself spending a lot of time on the movies sets, waiting for lights and sound and started smoking cigars,” he recalls. “Then the Grand Havana Room opened up down the street from my office in Beverly Hills and I became one of the founding members and would go there after work to relax and smoke cigars.” The lounge became a celebrity hangout for stars like Mel Gibson, Demi Moore, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Bruce Willis, and Patel became cigar buddies with them. Around this time, he started manufacturing cigars in Honduras and organized four or five cigar dinners with Schwarzenegger in the star’s restaurant and things really started to come together. During this period, Patel continued to practice law, but finally decided to chuck it all for the cigar. “I thought I’d better learn everything about tobacco, because I really didn’t know much and it might be something lucrative,” he recalls. “I started spending a lot of time in Honduras and Nicaragua on the plantations, learning about the farming, the fermentation, and the curing process, and I blended hundreds of cigars till I educated my palate on the difference between Honduran, Nicaraguan and Dominican.” He looked at people who had been in the business a long time to see what they were doing right and tried to emulate them and do it better. Then, after fully educating himself and researching the business for five years, he sold the law firm and moved to Florida. He says, “I’ve been doing it full time since and it’s become one of the top companies. This is our tenth year in the business. We are probably among the top two or three cigar companies in the world.” Indian Tabac has several lines including “Super Fuerte,” “Cameroon Legend,” “Fire” and the “Vintage Series.” The company has 3,800 employees in Honduras, grows its own tobacco, but it also buys large quantities of tobacco from some of the biggest and best growers of Cuban seed tobacco in the world based in Nicaragua, Honduras, Dominican Republic, Brazil, Costa Rica and the Cameroon. While generally cigars like Puros are made of fillers and wrappers from the same region, Patel likes to blend tobaccos from different regions. The company is known for its unique blends and all the cigars are blended by Patel himself in a time consuming process that can take up to a year. According to Rob Rimes, who works closely with him, Patel is inspired by different qualities of topnotch cigars – the quality of Padron, the construction of Davidoff and the consistency of Fuentes, while also keeping an eye on the price. Savvy Life magazine wrote: “Rocky follows cigar trends like some investors monitor the NASDAQ. With a Nextel phone in one hand and a 200 meter sprint to the jet’s gateway, he’s always on the move – and for good reason. He’s the new ‘Wonder Boy’ of the cigar industry.” In 2003, Patel created the “Rocky Patel Vintage Series,” which is made of premium quality aged tobacco. To make a dent in a tightly controlled industry, he had to come up with a savvy marketing plan. Ask him whether it was tough breaking in to the cigar industry and he responds, “Yes, it was because I was not of Cuban or American descent and all the cigar makers had a long tradition from Cuba or from Central America and had it as a family business. I was an outsider looking in.” Undeterred, he spent a lot of time going door to door, from retail shop to retail shop, covering over 600 cities in 700 days. He did endless rounds of events, promoting the product, meeting with retailers and organizing cigar dinners and a national advertising campaign. Meeting retailers one on one, city after city, he built personal relationships with cigar stores and soon the name Rocky Patel took on a boutique brand name status. “People called me the ultimate road warrior, because I just got out and pounded the pavement. I got the product out there and slowly built up a sales force and moved it from there. That’s how we launched it,” he says. The Rocky Patel cigars are known for their quality and also for how well the tobacco is fermented and aged. He says, “We are known for a rich, complex cigar that delivers a lot of flavor, but it is very elegant and balanced so there’s no harshness, no bitterness. They have a nice ash and you can smoke them to the end without any sour taste in your mouth.” Critics seem to agree: The “Vintage” line received yet another 90 rating from Cigar Aficionado. The 1990 Torpedo earned the honors in the February 2006 issue, scoring 1 point below the Padron 1926. How did his family react to his giving up law to become a biddi-wallah? Patel, who did his undergraduate and graduate studies at the University of Wisconsin, admits his parents weren’t too happy. “They were shocked when I told them I want to go into cigar making. It’s certainly not something someone from our Indian ancestry does. But now they are quite happy.” Yes, the jingle of millions can overcome quite a few inhibitions! “Giving up law was difficult, because I had built up the law firm myself from one person to 14 attorneys working for me,” says Patel. “But they were long, hard days and I got burnt out practicing law. I was tied to the office from 8 in the morning to 10 at night and this is much more fun. Now I get to eat, drink and smoke for a living!” What Patel likes best is the chance to meet all kinds of people from blue-collar workers to cardio-vascular surgeons to celebrities: “The power of cigars is unique, because you meet so many people. If you have a cigar, it opens the door to so many opportunities.” He’s met everyone from talkshow host Rush Limbaugh to basketball legend Michael Jordan and CEOs of major US companies. is a fan of his cigars. He’s also involved with cross promotions with Scotch Whiskey, Budweiser Beer and Cadillac. His cigars have also reached some cigar lounges, restaurants and hotels in India, including Indigo in Bombay. “The hardest part is cracking the barrier of being somebody that’s traditionally not into this business and it took a lot of passion and hard work and everyone in the industry refers to me as the hardest working man in the business,” says Patel. “I’m very driven, I’m a perfectionist and I always like to make the finest things in life and I also enjoy the finest things in life.” Does he smoke cigars daily? “I don’t smoke every day, but I’m a fan. I enjoy cigars like I enjoy fine wine, nice clothes, nice things, everything within reason.”

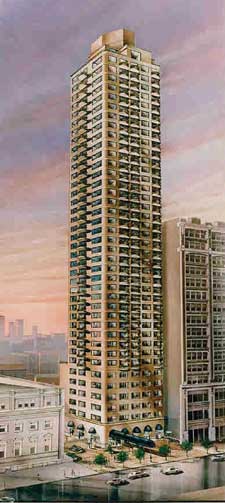

From Naples, Florida we move to New York City where real estate developer Arun Bhatia has just put the finishing touches to his latest flight of fancy:139 Wooster, a $55 million building in the heart of hip and upscale Soho. The city is dotted with over a dozen high-end condos, co-ops and rentals all created by Bhatia. Putting up grand structures was something Bhatia was born to do – it runs in his genes. He is the son of Ishwardas Bhatia, a real estate developer who was putting up buildings in the 1940s in Karachi. After partition in 1947, the family fled to Bombay with practically nothing, because, like many in the business, his father had reinvested all his wealth in buying more land in Karachi. Bhatia, who was born in 1952 in Bombay, knows the family lore about how the family fled from Karachi and lived in refugee camps for a year, close to Mahalaxmi, which today is the site of grand weddings. Gradually his father re-established himself and restarted his business. He always took the young Arun with him to construction sites and that became his playground. “Every Sunday since the age of four I accompanied my father to all the construction sites and once I was 12 or 13, during vacation I used to work with him, watching him in action,” says Bhatia. “I was given every kind of responsibility you can think of – from interacting with the laborers to accompanying my father to meet heads of banks.” After getting his bachelor’s in civil engineering, Bhatia came to New York for higher education. When he left India he had no intention of staying abroad permanently, but he also wanted to be his own man, and he knew it just wasn’t possible with his father, who had a very strong personality with very firm views on how things should operate.

“You could not disagree with him and I sensed that and the thought started in my head that I wanted to so something on my own, because in our society no matter how hard you work people always say ‘Oh, he got it all because of his father.” The senior Bhatia was building apartments for a different time and place, after the partition, so they were reasonably priced buildings for mass consumption. Arun Bhatia, however, has developed luxury apartments whose signature is fine detailing and superior materials. He signature tagline: is “Another distinctive development by Arun Bhatia.” His buildings in Manhattan include the Strand, the Dunhill, The Whitney and Capri. The National Association of Home Builders awarded the Strand its Gold Award for the best project of the year in 1989. His latest is 139 Wooster, in Soho, a luxury building with plush amenities, designed by the noted architectural firm of Beyer Blinder Belle. What kind of a feeling does he get when he passes the buildings he’s created and sees people living there? “I feel very proud. I really want to make a mark especially in a city like New York where the whole world looks at you.”

He walked Little India through the fascinating process of the rise of a skyscraper from start to finish, from scouting for land to putting up the structure, which can take up to two years, dealing with brokers, architects, engineers, and workers. He says, “I’m basically like a music conductor, because I’ve to keep all these hundred different people sort of in line, make sure they are all working toward the same goal within the same time frame.” Developing luxury hi-rises is about risk taking: “You could lose money on a project if you don’t complete it in a timely manner, especially in New York because here the labor is probably the most expensive in the world. An average carpenter makes $900 a day and an electrician makes $1,000 a day, so you can’t afford any delays.” He adds, “Obviously banks are not going to lend you money unless they see substantial investment on your part and some risk on your part. If you have a $100 million project, the chances are banks will give you $70 million and expect you to put up the remaining $30 million. The way it works is when the project sells, the bank get their money first and then only you can recover your own capital and get the profit. The builder takes a tremendous amount of risk.” While some builders join with other investors to spread the risk, Bhatia, with a few exceptions, prefers to work on his own, and be his own boss. He says, “It’s very difficult to run a development project unless one person has the authority. You’re making split second decisions every day and so a project cannot be built by a committee.” Besides his own projects, Bhatia also runs the AIB Management Corp., which provides developing expertise to other companies. His recent ventures include collaboration with universities to provide high rise student residences. The Capri, a $80 million 46-story luxury hi-rise, sold the first 31 floors to Marymount Manhattan College for student housing. The luxury Chelsea Regent accommodates 201 students from The New School. Thanks to Bhatia, college students are living the Manhattan lifestyle! “I love this business of creating something out of nothing,” says Bhatia, who is as fascinated by construction today as he was when he used to accompany his father on his rounds decades ago. “I want to create something that would obviously last hundreds of years and people would look at it and say, ‘Someone did a nice job.'”

We all know the trauma of batteries which run out just as you need them – say, when you’re just about to shoot the picture of a lifetime with Bill Clinton! Along comes Sankar Dasgupta, CEO of Electrovaya, a Toronto-based technology development company, whose proprietary Lithium Ion super polymer batteries can keep a laptop running for up to 24 hours. This alone would have endeared him to frustrated technocrats everywhere, but he has several other innovative products including the external Power Pad battery series that deliver up to 10 times more runtime. Electrovaya, which he co-founded with Jim Jacobs, is listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange and was rated as the fastest growing technology companies in Canada. It has over 200 global patents and awards to its credit and its 156,000 sq. foot manufacturing plant produces innovative batteries, computers and automotive systems. The young Dasgupta grew up in a prominent family in Calcutta, where both his parents were lawyers and his father had been involved in the Independence movement. “Like many Indian families there were enough scientists and doctors and engineers in our family,” he recalls, “We were always encouraged to be curious about how things worked.” After doing his undergraduate studies in Calcutta, Dasgupta studied for a PhD at Imperial College, London. He says, “It was an amazingly scientifically challenging place. While in most places you study, study, study and write papers, I found Imperial to be a very creative place, interested in making things work.” When he was only 22, he invented an electrochemical system for cleaning up the environment, filed a patent for it and began looking for investors to commercialize the technology. He wrote to various companies and heard back from a Canadian venture capitalist and together they started a new company. The electrochemical system he had invented worked well to remove cyanides and heavy materials from industrial waste and won awards, and was also adopted in about 30 cities, including Cincinnati and Chicago. He recalls, “We grew quite fast. We started with one employee and grew to 105 people in 3-4 years time.” A few years later, he sold out.

Since then Dasgupta, who’s also an adjunct professor of engineering at Toronto University, has been involved in several other inventions, including an advanced polymer battery, which packs a lot of energy in a very small weight and small space, making it ideal for mobile computers. “This is a plastic battery and so is malleable. It can be made into different sizes and shapes, even thin like paper,” he says. “While a typical laptop runs 2-3 hours on a battery, the run time with these batteries is 7-8 hours. These batteries are also used by NASA. They have what they call a ‘critical one mission’ where astronauts wear the suit and walk out into space and they need a power system for their life support. NASA went around the world looking for the best batteries and they decided to take our system.” Why has no one else thought of this technology? He laughs, “There are massive amounts of battery wars going on. You just have to be sort of lucky – it has to be right time, right place. I think timing is so important in invention.” Electrovaya partnered with Microsoft to develop the Scribbler, tablet PCs that are just 3 lbs in weight. Says Dasgupta, “It’s got a nice 12.1 inch screen and is very light and the battery lasts for 7 to 8 hours. It’s very thin and light, so it’s the most mobile portable computer possible.” Other products include the Power Pad, which can be attached to a mobile computer to enable it to run for 10 – 20 hours, which Electrovaya is selling predominantly to hospitals. Dasgupta’s current passion is zero emission electric vehicles and he believes that a lot of time and energy was wasted on developing hydrogen fuel cell cars: “Why did the world go after this for two decades and spend $20 billion trying to develop clean transportation based on hydrogen fuel cells? It was a very bad idea because for 20 years the world lost its direction; it chased a technology which was guaranteed to fail.” In the meantime 750 million cars are burning oil, and the world is beset with a dependency on oil, climate changes and urban health problems. He believes the electric car will be the solution to the energy crunch and to the health hazards caused by urban pollution. Electric cars with their limited range and frequent need for charging have been generally regarded as novelties and not practical for daily life, but Dasgupta’s innovative car seeks to change that. His zero emission vehicle, the MAYA-100, is powered by energy-dense, lithium-ion SuperPolymer technology. It is equipped with a 35 to 50 kwh battery pack and this long-range vehicle can travel 300 miles between charging. Once again, as in the computers, the batteries are key to success. A recent electric car in the news was Tesla Cars, which was launched in California. “I think it’s a difficult design. These are not flat polymer batteries. What they are doing is buying the standard cell phone batteries from China and connecting 6,800 of them together. It’s insane!” he says. “You need the battery to be ultra safe and the way the cell phone and mobile computer batteries are made they can’t handle overcharge very well.” Dasgupta knows it will be an uphill task to get the world weaned off oil and into the electric car, because it’s disruptive technology requiring automakers to embrace a new technology: “Where the carmaker makes his money is from the engine and the drive train, not the seat and the body, which is made by somebody else. It’s an electric drive train and so there’s no value for the carmaker and it’s a new technology which the company will have to learn.” The prototype of Maya 100 is available in Norway and a few are already on the streets of Toronto and Dasgupta hopes to start production next year. The operating cost is lower than 80 percent of gasoline-run cars. “You will save a lot of money during the life of the vehicle and the operating costs go down dramatically,” he says. ” The capital costs of the car in volume production will be the same as that of internal combustion engine cars.” Does he himself drive an electric car? He says, “Yes, absolutely. The other day I borrowed my daughter’s car because my electric car was somewhere else and it ran out of gas! Because I always drive an electric car I never think of filling up on gasoline. So there I was, driving her car and suddenly it stops in the middle of the road.” Do these cars have weird, futuristic shapes or do they look like regular cars? He laughs, “No, no they look exactly like a normal car. What we did was take the chassis of a regular car and converted it into electric. So that could also be a possibility where Electrovaya could team up with auto companies and use their chassis to make electric cars.” Dasgupta is a believer in the power of imagination and in treading off the beaten path. He says, “I always tell people, including my own children, that follow your ideas and do take risks. It’s not that bad. Part of the risk taking is you have to keep pushing your ideas and convincing others.” He adds, “I’ve always been driven by curiosity and I grew up with Indian values where you’re not driven to be materialistic, but more to be thinking people, with good values.” His four children have seemingly inherited his genes – his oldest daughter, who graduated from Oxford University, works with him on the electric car, and a son has a PhD in nanotechnology, while the other two are studying science. And what gives him the most satisfaction? “Nowadays, it’s always a group doing research together and people are always thinking and so working in a team is very satisfying. It’s like doing a puzzle – getting a nice idea is very adrenalin-driven.”

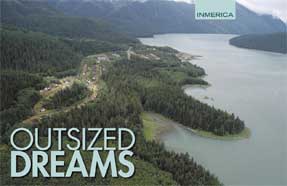

Many people might consider buying a condo or a townhouse or perhaps even a mansion. But Krishnan Suthanthiran bought an entire town – sight unseen! And all for cash down. (The asking price was $7 million). Estimates to build such a town at today’s costs run as high as $250 million. The Tamil Nadu native, from the district of Dindigul, is a visionary who saw a dead mining town and pictured the possibilities of bringing new life back to this beautiful ghost town of Kitsault. Even before this acquisition, Suthanthiran was already an over-achiever in the field of innovative medical products, as head of Best Medical International, a Springfield, Va., based company known for its pioneering work in radiation and brachytherapy products. But the world’s imagination seems to have been really transfixed by his recent acquisition of Kitsault, which has its own fascinating history. In 1979, the remote pristine Observatory Inlet of northern British Columbia, behind the Alaskan panhandle, was known for its rich deposits of minerals. The mining conglomerate of Phelps Dodge wanted to mine its molybdenum and built an entire town to accommodate its workers. Kitsault was an ambitious undertaking, with more than 100 single-family homes and duplexes, seven apartment buildings for a total of 202 suites. It even had a modern hospital and a shopping center, restaurants, banks, a theatre and a post office. After the workers arrived life thrived, but just 18 months after its inaugural, the molybdenum demand died out and prices crashed. Kitsault was abandoned and became a ghost town. If descriptions of Kitsault are to be believed, it sounds like a Shangri-La. The official website boasts: “There is 2.4 kilometers of waterfront teaming with fish and crab, and along the manicured boulevards apple trees hang low with fruit that no one has ever picked. The town is surrounded by snow-capped mountains that have never been skied and there are eight glacier-fed streams that support salmon within a 20-minute walk of the town center.” It was a town without people, a town time forgot – until Suthanthiran came along with his larger-than-life ideas and risk taking. He is toying with several possibilities from resorts to a movie studio to energize the region. He plans to rename the town Chandra Krishnan after his parents and it will be interesting to see how this Indian immigrant revitalizes this unspoilt part of British Columbia. Kitsault may indeed have found a savior who will respect its environmental wealth and native culture. People have tried to dissuade him, but as he says, “You could list all the issues and walk away from it. But I didn’t grow up that way; I had to go through a lot of challenges.” Years ago, his father, who owned a small grocery business, was struggling and even finding money for his schooling was difficult. “I used to buy used books for school and not make any notations on them, because I would resell them to buy books for the next class,” he recalls. “Once my grandfather gave me Rs. 15 for my examination fees and a relative took it away. I spent five days crying and finally my father found some money for the fees.” He did not even have enough money for his college tuition. A friend’s father joined up with other friends to put together that small – yet so very big – amount for him and he’s never forgotten that gesture or its ultimate importance in his life.

The money bore rich dividends. Suthanthiran secured a scholarship and went on to a research assistantship at Carleton University, Ottawa. His first job at the school cafeteria was as a dishwasher for $1an hour. He says: “You worked eight hours a day and then you got $8, minus taxes.” Suthanthiran graduated from Carleton’s Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, and hitchhiked his way to the United States, where he spent hours every day at the labor department, trying to get an engineering job. Today he is president and founder of Best Medical International and has also acquired several other medical companies. He is setting up Best Medical offices in India, Dubai and China. In fact, his interests flow in all directions – and his latest acquisition is a media production company in Canada. It’s a step linked to his purchase of Kitsault, for which he has some very dramatic plans, including a nursing school, conferences and retreats. Does he think it was a smart business move to put millions down for this abandoned town? “If I was looking strictly for investment, then there were many better opportunities,” he says. “My financial advisors in fact advised against buying it. Initially I felt it was a shame that such a beautiful town was sitting empty and not being used. I thought it was a crime.” After buying it, ideas have been percolating and, as he says, evolve over time; they don’t happen overnight. He hopes to use Kitsault for furthering health, education and non-violence philosophy. “I’m going to be setting up an artists’ colony and the initial plan is to have 300-400 artists living there with free lodging and we want them to develop their skills,” he says. “In the fall we plan a Mahatma Gandhi Film, Music and Television festival to promote non-violence in entertainment, because we live in a very violent world.” The plans will be mapped out within the next couple of years and include the production of films. This multimillionaire lives very frugally. He doesn’t own a car and often goes watch-less, because he says he can read the time on his cell phone. But truth is that the true value of a dollar is not lost on him. He knows how far money can go in educating future generations. He was the only one in his family to complete high school and knows that lack of education means lost opportunities. Today he funds over 100 scholarships in India, as well as operates a school and hospital in his native town, besides donating $100,000 to his alma mater in Canada. He says, “Every dollar I save is a dollar toward education.” Amazingly, Suthanthiran didn’t even see Kitsault before buying it, since he was busy acquiring another company in New York at the time! He says, “This is blind optimism. Most people wait for opportunities, but as an entrepreneur you go out and seek opportunities.” And so, there you have it – a world that is more fun, more colorful and more sustainable because of the risks these men have taken. For all four immigrants, working in very different fields and different cities, the common link is a passion for their work. Just goes to show the power of the imagination and the fuel of immigrant dreams, which can propel cars without gas in their tanks, raise the scaffolding of shimmering skyscrapers, give life to an abandoned ghost town. And yes, let’s not forget the power of a Patel brewed cigar, blowing smoke from sea to shining sea. |