Arts

Notes From A Full Life

"From mastering an instrument, we ourselves became instruments of something that possessed us."

It’s remarkable—but in no way surprising to those who have followed his career as a musician—that even in the last months of an eventful and flamboyant life that ended in a San Diego hospital, Pandit Ravi Shankar played his beloved custom-made sitar with the same vigour, gusto and focus that had marked the performances of his early youth. Video clips of a recent public concert in Bengaluru show the lion in winter—frail frame, lined puffed-up face and bushy white beard—seemingly lost to the world but in no way diminished as a performing artiste. He was absolutely on the beat with his strong yet delicate plucking, and coaxed the most sublime musical phrases out of what is essentially—despite all the carvings and the finery—a wired piece of wood.

In fact, much like a flame that glows at its brightest on the verge of being extinguished, Ravi Shankar reportedly was at his restless, creative best in the fragile weeks before his death. He played his last concert in Long Beach, California in a wheelchair, his nose strapped with an oxygen mask. “I feel very strongly that I’m a much better musician than ever before,” he told an interviewer. “And I have trouble sleeping these days because so much music is going through my head.”

Few will ever doubt that Ravi Shankar’s journey from the Bengali quarter of the hoary riverside town of Varanasi through the razzle-dazzle of the world’s most glamorous cities and cultural centres was indeed a charmed one. He was a veritable child of destiny. It is not unusual for an individual’s life-choices to be determined by cataclysmic global events. But in Shankar’s case, it almost seemed as if he anticipated such events, and rode them to greater glory.

Few will ever doubt that Ravi Shankar’s journey from the Bengali quarter of the hoary riverside town of Varanasi through the razzle-dazzle of the world’s most glamorous cities and cultural centres was indeed a charmed one. He was a veritable child of destiny. It is not unusual for an individual’s life-choices to be determined by cataclysmic global events. But in Shankar’s case, it almost seemed as if he anticipated such events, and rode them to greater glory.

In the late 1930s, after several years of travelling as a dancer with his older brother Uday Shankar’s troupe across Europe, the centre of world culture at the time, a teenaged Ravi Shankar opted to give up dance and take up music instead, under the tutelage of a senior troupe-member—the sarodist Allaudin Khan.

By the mid-1940s, thoroughly versed for eight spartan years in the Hindustani classical style of sitar playing under the stern eye of his legendary teacher, Ravi Shankar ventured to Bombay. Here he played his heart out, in a manner of speaking, holding listeners enthralled in all-night concerts with little expectation of financial reward. For the latter, he preferred the safe haven of a salaried position at the public-sector All India Radio which offered him and his new family a semblance of material security. But uncannily, after joining AIR, Shankar found himself at the cultural forefront of post-Independence India’s campaign of nation-building. He was instrumental in setting up the national orchestra called Vadya Vrunda, and in composing a whole range of popular music pieces—from the immortal Saare Jahan Se Achha to the short introductory and interlude pieces which radio listeners identify with to this day.

In the mid-1950s he quit his AIR job and headed west, undertaking long concert tours covering Europe and particularly USA, the emerging global power—both economic and cultural. It was soon the era of the hippies and the Beatles which saw the rise of flower power, and whose adherents chose to reject western values and embraced Eastern mysticism. The exotic strains of Ravi Shankar’s sitar served as a perfect backdrop for these salvation seekers.

And Shankar himself—fluent in French and English, among several other languages—proved to be a master at wowing Western audiences with his charm and wit.

If you went solely by the extent of the media coverage of Ravi Shankar’s death last month, you’d be forgiven for believing that he was India’s greatest ever musician. That, by any discerning critical standard, would surely amount to stretching the limits of credulity, and even the claim of his being the greatest sitarist would be up for fiery debate. After all, in his more candid moments, Shankar himself would openly agree that Nikhil Banerji’s sitar-playing was so much more soulful than his own. Vilayat Khan and Halim Jaffer Khan would, at the very least, be equal contenders.

Ravi Shankar’s forte, on the other hand, lay in the richness of his imagination, in extending the frontiers of his art for which he not only sought to rap with practitioners of musics far removed from his own; he even modified the structure and string-arrangement of his instrument to allow for such improvisations. Whether these experiments proved successful in enriching the musics themselves is but a moot point. They did however open the world’s eyes—or more accurately, its ears—to a new sound. And they did bear the unmistakable stamp of a genius at work, intent to explore vistas beyond those that were obvious. Nothing was sacrosanct in this pursuit of his artistic goals, nothing could impede his insatiable quest for artistic satisfaction.

One of his avowed artistic goals was to connect musically with the West. For this, Ravi Shankar brought to his musical performance the presentation techniques that had characterized an Uday Shankar dance concert. Ambience and stage-craft mattered. And so, in an unprecedented move, Ravi Shankar introduced professional lighting and sound techniques, and crowd-pleasing modifications in his playing format.

One such modification involved tweaking the traditional alaap-jod-jhala order in which a Hindustani classical raag is typically expounded in an instrumental music concert. Defying tradition, Ravi Shankar would begin his gig with short light pieces that would sound melodious yet playful—and were therefore accessible—to the untrained ear. He would then take a small break, encouraging the percussionist to thrill the audience with intricate rhythmic patterns that would send the beat-oriented listeners into raptures. And finally, satisfied that the crowd had tuned in to the Indian musical ethos, the sitarist would emerge in his traditional avatar and play out a raag in all its pristine grandeur, unfurling it step by elaborate step till he climaxed the concert with his signature gesture of thumping the drum for the very last beat. It was great music no doubt, but even greater theater.

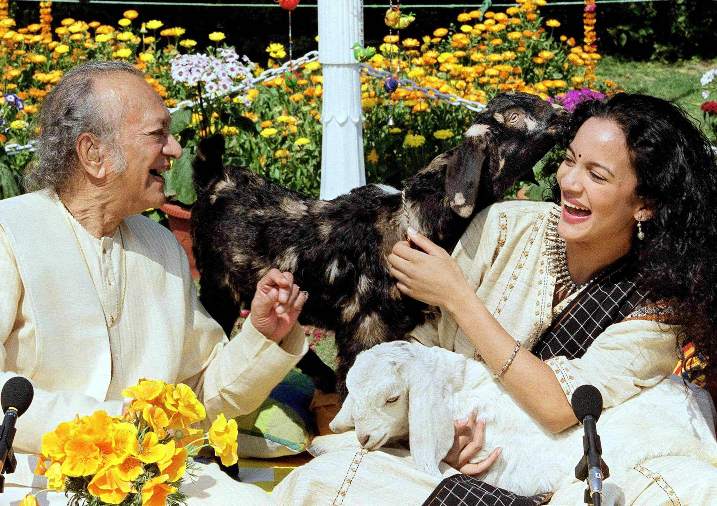

Ravi Shankar in performance in 2012

The approach earned him many fans—and more than a few detractors as well. Purists lamented that the great Ravi Shankar had sold out to the West, and in the process had sullied an ancient and sacred art-form. “Those foreigners will start climbing the walls of the auditorium in boredom and frustration if I play an alaap for an hour,” he tried explaining to the critics, but in vain. They wanted much more solid evidence that he had not abandoned his musical gharana or lost his classical bearings. Shankar then scheduled a mandatory concert in India every year where he would grind out an alaap for an hour or more, and leave the purists satisfied that the firangs had not corrupted his music. For Shankar, these concerts were part assertion of his musical roots, and part quasi-penance for his dalliance with foreign lands, their cultures and their musics.

The firangs, on their part, loved these dalliances. Ravi Shankar truly reached the zenith of his popularity as a versatile musician with his pioneering forays into world music—notably his collaborations with the Beatle George Harrison, the violinist Yehudi Menuhin, conductor Zubin Mehta, and the minimalist Philip Glass. He was honored with the Grammy and a host of other awards for what has come to be loosely—and quite erroneously—termed as “fusion” music by lesser music critics and impressionable headline-writers.

Erroneous because the way in which Ravi Shankar conceived the music and laid the tracks for those albums with the help of his collaborators, the individual musical contributions of Shankar and his collaborators never really fuse into one another to create a new and distinct entity. At the risk of over-simplifying what they did in tandem, one could classify these works into two categories: one where Ravi Shankar would simply guide the player of a foreign instrument into following the contours of a raag as notated for him in written form; and the other where the foreign instrumentalist would play a piece from his repertoire and Ravi Shankar would respond intermittently with a compatible-sounding melange of musical phrases with the flavour of an identifiable raag. Either way, did the albums truly qualify as fusion music?

Ravi Shankar was too smart a man and too insightful a musician to delude himself into believing that he was creating genuine fusion music. “I’ve never called it fusion myself,” he once told an interviewer. “One can, at best, call it experimental music.”

But the albums served to bridge the centuries-old gap between listeners of Indian and western music, and expanded their sensibilities. Not many are aware however that Ravi Shankar also collaborated with musicians from the Far East: Hozan Yamamoto and Susumu Miyashita of Japan, exponents of the shakuhachi and koto respectively. In India, the bridge-builder played his part in bringing Hindustani and Carnatic musics closer by including Carnatic musicians in his foreign-touring orchestras and by performing regularly for Bengaluru audiences which he considered special because they appreciated both Carnatic and Hindustani styles. The now renowned violinist L.Subramaniam debuted on Shankar’s Vadya Vrunda, which gave him international exposure.

It was this open and inclusive approach that helped Ravi Shankar straddle with ease the elitist and rarefied universe of Hindustani classical music and the grubby world of the street. He was as much at home playing for connoisseurs at the most prestigious mehfils, as he was composing ditties for Asiad Games for the consumption of the hoi polloi.

Perhaps Menuhin captured Ravi Shankar’s genius best in the afterword he wrote in Ravi Shankar’s autobiography: “From mastering an instrument, we ourselves became instruments of something that possessed us.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login