Life

Men In Skirts

Are you less a man in a lungi?

|

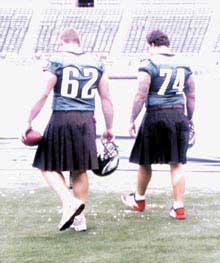

Would a man be any less the man for dressing in a skirt? Does he lose his sense of power if he doesn’t wear the pants in the family? If Prince Charles and Sean Connery can wear kilts, David Beckham a sarong and David Bowie a dress,why can’t ordinary men wear a skirt?

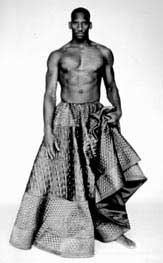

Bravehearts: Men in Skirts, a provocative exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, celebrates the skirt as a male garment and as a symbol of challenging moral, social and gender codes and thus redefining the ideals of masculinity. After all, women are forever stealing men’s shirts, suits and even ties! So, isn’t it about time that men started doing the pilfering? In fact, there was a time when skirts were perfectly acceptable attire for men: in many ancient civilizations wrapping provided the most basic skirt form. In those days the exposed male body signified virility and youth, and indeed who could be more warlike or manly than those ancient Greeks, Romans and Egyptians? From the wrapped waistcloths of the Egyptians to the tunics, mantles and togas of the Greeks, men enjoyed untrammeled freedom. Fashion designers have drawn inspiration from these ancient cultures, the Scottish kilt as well as the cultures of Asia and Africa to create their own versions of skirts or non-bifurcated garments, that is garments that are not divided down the middle. Asian, African and Middle Eastern attire such as the sarong, dhoti, lungi, caftan, kameez, the Chinese robe and the kimono are increasingly turning up on the catwalks of fashion capitals in the west. Urbanized Eastern men may have opted for the confines of the suit and the noose of the tie, but Western designers are turning to the freedom of the free-flowing ethnic garb. The East India Company also did its bit for fashion, queen and country during the British Raj: it popularized a garment in England which had Indian roots – the “India” gown or banyan based on the chogha or open-fronted gown worn by royalty. Interestingly enough, this is perhaps the only skirted garment in the form of a dressing gown that today’s men can wear, without stirring controversy.

Not surprisingly the Met exhibition about breaking taboos is sponsored by that daring designer, Jean Paul Gaultier. He created his first skirt for men in 1984, and has in fact presented skirts in every succeeding collection, each more elaborate than the other. He says, “As a result of this exhibition, our western society will perhaps accept the fact that men wear skirts, just as 40 years ago it was accepted that women would wear trousers.” Gaultier has promoted the dhoti as a unisex fashion, dressing both the man and woman in black dhotis with matching jackets. He has also promoted the sari in his menswear collection, creating sari-suits, including a short version in a blue and white pinstripe, presumably for the office! Andrew Bolton, the associate curator of the Men in Skirts show and author of the accompanying book, believes that far from feminizing men, skirts actually reinforce their virility. The exhibition features more than 100 items drawn from The Costume Institute’s permanent collection along with loans from cultural institutions and fashion houses in Europe and America, showcasing the work of scores of designers from Georgio Armani to Paul Smith who have used the skirt as a means of bringing novelty to men’s wardrobes and creating a sense of individuality. Men have lost their skirts fairly recently, for as Bolton explains, “Since ‘the great masculine renunciation’ of the late 18th and early 19th century, men have tended to follow a more restricted code for appearance. From the 1960s, with the rise of countercultures and an increase in informality, men have enjoyed more sartorial freedom, but they still lack access to the full repertoire of clothing worn by women.” Designers like Vivienne Westwood, Roberto Cavalli and Sean Puffy Combs have reinterpreted the African caftans while Armani has turned the sarong into a garment of escape for Western men. Roy Krejberg for Kenzo even designed sarong suits with tailored jackets! This interesting mix and match is actually happening in the Arab world, where men often wear their caftans with Western jackets. This East West trend has shown up in the collections of designers like Miguel Andover and Rosella Jardini for Moschino. Donna Karan as well as Dolce and Gabbana have shown lungi-like waistcloths on male models on the runway, paired with chunky sweaters. Far removed from its context of Village India, the simple wrap acquires a fashionable chic as the models careen in the style capitals of the world. “In terms of both design and styling, the results are often highly exoticized versions of these ‘culturally authentic’ garments,” explains Bolton. “Exoticism involves a dual process of nostalgia and alienation, a longing for a place that one has never been, or a culture that exists only in the Western imagination. Non-Western cultures are often perceived as static and timeless – a utopian, genderless paradise.” So even as Western designers yearn for clothing that is free and unfettered, why are Eastern men giving up their authentic wear for the tyranny of the pant? Little India asked Indian-American fashion designer Anand Jon, who hails from Kerala – the land of the lungi and the munduh, waistcloths that the Malayalees have worn for centuries.

“Having grown up there, I can tell you that most people look forward to winding down their day and getting into their munduhs and relaxing,” says the designer who will be launching his menswear line next year, and already designs shirts for rock stars, including Bruce Springsteen. “Pants and shirts and suits are definitely the outcastes and the exception to the rule. They are worn only because of economic reasons, dressing in western clothes would help one to get work. The only exception is jeans and jeans have become a culture in itself. But the comfort and the androgyny of draped clothes is something most people are very secure with, particularly in their sexuality, so that you don’t have to be that distinct in what you wear.” In the West, it is only the youth or those in countercultural movements such as punk, grunge and glam rock that have adopted the skirt as their mantra of rebellion or self-expression. For most men, though, skirts or draped wear does not seem to be in their immediate future. As Bolton points out, trousers for women became acceptable largely because society reassessed its definitions of women and femininity but this re-evaluation has not happened for males. “For many men, the feminine connotations are too potent to overcome the fear that by wearing a skirt, their gender identity might be brought into question. Ultimately, men’s roles in society as well as society’s definitions of masculinity need to change before skirts become an acceptable alternative to trousers.” In Asian countries, men do seem to have a better deal than those in the West. After all, it’s perfectly acceptable for a man to switch between a three piece Western suit and a salwar-kameez, a robe or a lungi. Nowadays, fashion conscious Asian men are adopting long flowing robes, jackets and dhotis or baggy kameezs and salwars, with a shawl thrown over the shoulder.

“There’s almost a symbiotic relationship between the body and the fabric in draped wear which kind of bounces and dances around the physical body whereas the fitted clothes contain the body and almost limit it from movement,” says Jon. “In the work environment draped clothes are not accepted that much because they embody freedom, particularly work, as we know it in the western civilization, is not about freedom. That’s why suits and monochromatic colors are so popular because the concept of work as dictated by the western civilization is about conformity. It’s about not standing out, it’s about performing a duty and getting out of there.” As he points out, it’s ultimately a question of each individual finding a balance of what works and where: “There’s no reason why people cannot be in that character and then at the end of the day shift into something that is much more personal, such as draped garments, skirts, lungis or caftans.” Way back in 1937 designer Elizabeth Hawes already understood this, when she created an Arabian Nights kind of robe for men. A big believer in skirts for men, she wrote, “The sheikhs of Araby, whose sexual exploits are legendary, wore skirts and they have never been considered sissies, to put it mildly. The American male is not only uncomfortable in his suits, but he has deprived himself of practically all the pleasures to be had from wearing colors, the feel of certain textures on his skin, the wind blowing on his body through his clothes, the sun and wind directly on his body or parts of it. That our men are not allowed to satisfy their souls in such simple human ways is a terrible thing.” Certainly seems time for a Dhoti-Revolution! |