Magazine

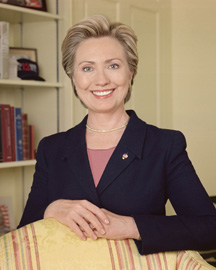

Lessons From Indira Gandhi for Hillary Clinton

The more we see Hillary Clinton, watch her unfold herself and unfurl her strategy, the more we are forced to think of our own Hillary -- Indira Gandhi.

|

Indians bring a rare perspective to this election season. We know what it is like to elect a woman to lead us and then be led by her. As Hillary marches toward the presidency, Americans could well benefit from our privileged hreflection. The more we see Hillary Clinton, watch her unfold herself and unfurl her strategy, the more we are forced to think of our own Hillary – Indira Gandhi. There are, on the face of it, major differences between the two women. Hillary Clinton is engaged in a very different selection process. She is going through a grueling and open primary while Indira Gandhi was thrust into power through the back door. There were no primaries to run, only back room politics. Hillary does not have a certainty in her hold on the office as Indira Gandhi did. Hillary is in a culture where she can be called by her first name in public discourse, while Indira was always Mrs. Indira Gandhi. For a woman who is steadfastly ambitious and widely known to be brilliant, it is unlikely that Hillary has not studied other women who led their nations. Hillary’s and Indira’s lives have much in common. Perhaps the most revealing traits common to them are overcoming the impressions of others and breaking out with stubborn and steady moves of their own. For beginners, we often hear in the idiom of politics that Hillary invokes either total admiration or complete hatred. We can begin there because Indira Gandhi lives with that impression to this day. Both of them defy the feminine, strategic image that we have of women. Even in their leadership roles they don’t quite follow the “woman’s logic” in their thinking or decision making process. There is a feminist dream that if women ruled the world, or more precisely if mothers did, they would change the course of policies, from war to mediation, from fight to conversation, etc. Indira showed this was a myth and in a man’s world, there is no place for soft-hearted, context-oriented meditators. It turned out that the men preceding her, including her father, were softies. It was Indira who launched the campaign of East Pakistan/Bangladesh and it was Indira who supervised the nuclear program. These weren’t faint attempts to keep up with a man’s world; they were deliberately cold blooded moves with an incredibly strong backbone and a long strategic vision. Indira was consistent throughout, did not waver and held her own. All the while, she was ridiculed by those who thought they knew better. She was installed to run a “kitchen cabinet,” but when she entered the room, her guns were blazing. Hillary Clinton’s position on the Iraq war and specifically her own vote that legitimized it, have become the central topic of discussion about her candidacy during the past few weeks. Despite pleas, she has not apologized for her vote and it seems unlikely that she will. In fact, she has said, it would be worth risking votes on that count than apologize for a vote, which at the time, she believed in. Justifiably, the anti-war sentiment is high and strong in the country, particularly among Democrats, but Hillary is unwilling to budge. This hard-nosed insistence is not an indication of a closed mind (which the current occupant of the White House is credited with), but a strategic position that will yield dividends over time. That particular relish in upsetting expectations and then “taking the bull by the horn” approach characterized not just Indira Gandhi, but also former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. It’s an example of how women leaders have not quite turned up either as the patronizing caricatures that men painted or the markedly different thinkers and policy makers that feminists assumed they would. Instead, they have this rock solid and incredibly stubborn determination to get what they want, stay focused on what is at hand, use muscle when necessary and rule without flinching. There is lot to watch in Hillary as the campaign unfolds. With swarms of consultants around her, blessings from the Democratic Leadership Council (a relatively right of center wing), she is poised to follow the foot-steps of both Indira Gandhi and Margaret Thatcher. Unlike Indira, Hillary groomed herself to become the leader of the country. Indira was a chaperon for her father, estranged from her husband when he was alive and quite dis-interested in politics. There is every evidence that Hillary has been waiting for this moment. And, she has learned plenty from her husband, the great master of political maneuvers, and from her years of politics from Arkansas to Washington, D.C. But as she gets closer to the moment and closer to her purpose, she is very much like Indira. In each deliberate move, from health care to the Iraq war, Hillary has steadily carved a space for herself by going against the currents of opinion in her party. Fit to the style of politics here, she maintains a consistent position and slowly cuts down people she takes for granted, while building alliances with those closer to her own position. This style is similar to her husband’s when he campaigned, but even more akin to the strategy Indira used in her break from Congress. The Indira-wing of the party, then certainly more to the right than left, was shaped by the same moves. There was precious little of this building of alliances for her, but she was markedly focused in attacking those who opposed her and taking for granted those who offered support. The much vaunted “machine” that we hear about in the Hillary camp, has a familiar resonance. Their attacks, as witnessed recently at the start of the campaign, are strong, swift and merciless. Bill Clinton’s war machine pales in comparison. If right wingers fear that electing Hillary is surrendering on security issues and turning soft on defense or domestic issues, they have a thing coming to them. Hillary might turn the men around her into sissies in the mode that her presumed role model in India did. Both women emerged from substantial personal life traumas. In Indira’s case, it was her failed marriage, alive for theatrical reasons while her husband’s body was warm, but relegated to the background as she tended to herself and to her father. Katherine Frank’s wonderful biography on Indira Gandhi points out that Indira felt alienated from family life and was reluctant to show any emotion in public. She maintained just token warmth toward her sons while they basked in the limelight of their grandfather. The loss of her own father, the personal disappointments in finding a peaceful and serene life for herself, one she imagined in her high-minded schooling in Europe, were considered fairly alienating shocks for young Indira. Through all that, she was still standing and when the time came, she showed how she had handled it with true grit and steely nerves. For Hillary, the transplantation from Illinois and then from the nation’s capital, where she was involved in Pres. Nixon’s impeachment, could have marked a retreat. But she stayed in bland Arkansas with an ambitious husband to cultivate even bigger ambitions. When his tawdry scandal unfolded, she kept a steely cool and emerged a survivor from the trauma. Both women turned their personal experiences into political capital and kept marching. Both also spent most of their adult lives in the public eye, with varying degrees of attachment to it. But their personal lives, the details and feelings within, remained secret. Very little of Hillary’s autobiography Living History is personal. Her husband’s autobiography is a stylized and tactical personal confession. Hillary is keen to talk without talking. Her choice of “my husband” and “Bill” is calculated. She invokes her personal life only when absolutely necessary. This reminds us of Indira. Her own husband rarely made an appearance in her public thoughts. Her children or their spouses or children were present only as props. Indira rarely invoked her father, except in deep reverence, particularly when it was politically expedient. And, for the most part, her son Sanjay’s shenanigans or Rajiv’s hobbies remained behind the curtain, to be brought out when it was necessary, even then with a sense of detachment of a close observer, not that of a head of the family. Perhaps there is strength in all of this. That motherly kernel we believe women leaders have becomes a political tactic and not exhibits for the larger domain. Indira’s temper was legendary. The old fogies in the old Congress had never experienced anything like it. Before they could even utter another ha-ji, they would be cut down to size and shown the door. It was mostly the voice, from everything we know, but it had a potent power. There was more fear about Indira around her than devotion and admiration. She ruled with an iron fist. Soon, everyone realized that and she surrounded herself with men of far less intelligence and backbone. It was one of the tragic failures of her leadership. Her temper and temperament did not allow men or women of talent to survive around her and the entire entourage was mediocre. Hillary’s temper is equally legendary and if rumors are true, it involves more than words. We used to feel for Bill when he appeared with this or that bruise and rumors grew that telephones were flying. With ample bursts of temper to match, there is no evidence as yet that Hillary will surround herself with lack luster, incompetent and unthreatening men. But the temper is indicative of something else. There is in both women, an indomitable self-confidence. It is not bombastic nor overtly repulsive. Unlike Margaret Thatcher, there is a sense of warmth about Hillary and Indira. Underneath, there is fountain of energy and determination. Indira was able to transform that into charisma and Hillary has turned it on with magic appeal to vie to become the first woman president of this country. Hillary visited India, both as First Lady and then as a U.S. senator. From press accounts and her own book, it is clear that she realized how this was an opportunity to show her political acumen and cultural sensitivity. We see how she marks the territory for Musharaff and holds him accountable for the war on terror. There is, in equal measure, a guarded optimism about India and strong pleas for peace and restraint. Once she leaves the political theater, it is utter sappiness about poverty and global distribution of resources. All this with great regard for the Indian people and culture. Two different personas, one reserved for the world of politics and policy and the other for either the heart or the PR machine (or both). Indira’s own visits to the U. S. were equally double edged. She would not budge about signing the nuclear disarmament treaty. She would never compromise on India’s strength. But then she would appear in public forums or on TV shows to argue that the U. S. should do a lot more for the people of India and, for that matter, the rest of the world. It is the same two-sided approach she followed as prime minister. There were humiliating deals with the U. S. on grain and food and vocal and determined moves on socialistic and nationalizing policies within the country.

Kathleen Hall Jamieson speaks of the “double bind” for women in leadership. The problem for women is this: how do they reconcile their role as women and still become leaders in a world that is openly hostile to them. How indeed could they be feminist by becoming leaders in a historically distinguished mode and yet remain women, remain honest to their own achievements as women? For Indira, it was not a prohibitive bind. Despite being perceived as a soft, “kitchen-cabinet” pretty woman, she turned out to be strong willed, authoritarian, even despotic. She combined the two with great skill and made a place for herself. She did this in a culture that is ambivalent toward women, but by all means patriarchal. Hillary’s problems are similar. Perhaps at no other time in its history could this country use a woman president. With the increasing radicalization of most of the world, not just Muslims, pervasive doubt about U.S. intentions and a national identity crisis in a rapidly changing world, one would hope that a woman could bring about substantial change in tone and practice. But Hillary is in a political process that is brutal and not kind to those who are intelligent or visionaries. The only blessing is that if and when she gets there, she will be battle tested. There is evidence that the country is curious to hand its reins over to a woman, if not now, then soon. She can ride that sentiment. But for that, she needs to learn her lessons. If she has not learned them already from her predecessors like Indira, it is time for her to do so now. |

It’s still a long time to the elections. But if she is elected, Hillary will have crossed an important threshold for this country and for women around the world.

It’s still a long time to the elections. But if she is elected, Hillary will have crossed an important threshold for this country and for women around the world.  Both Hillary and Indira realize political expediency in their roles as leaders.

Both Hillary and Indira realize political expediency in their roles as leaders.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login