Arts

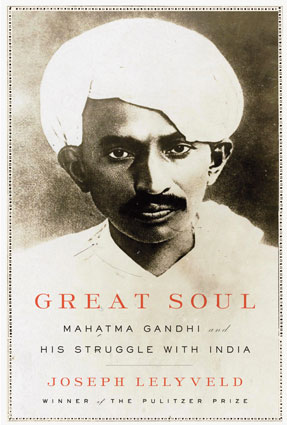

Joseph Lelyveld

| Were you surprised at the intensity of the controversy that your book Great Soul generated?

I thought the book might be controversial for other reasons, because in my reading of what I am doing I am being somewhat critical of the Indian political establishment for basically jettisoning Gandhi’s goal in this area of social reform and uplift and I identify with his sense that the movement basically played lip service to his goals. So, I thought that that might be controversial — a foreigner making those statements. But in fact no one has paid much attention to that which I consider to be the major theme of the book. I had not thought of the [Hermann] Kallenbach thing as controversial, so I was surprised when it went viral. It all happened very fast. It started with the Wall Street Journal article which, in my mind, was a very irresponsible trashing of Gandhi based on a very partisan old fashioned Tory reading of what I wrote by an Englishman and that then produced the London Daily Mail article, which really brought it down to the gutter and that hit Indian websites long before anybody in India had a chance to look at the book. The assertion that the book says that Gandhi was bisexual and racist was created. The book was banned in Gujarat by the great Gandhian Narendra Modi before it had appeared. It is kind of breathtaking to be at the center of this sort of thing.

There have been several other books that are more focused directly on aspects of Gandhi’s sexual life, while in your book it is a very tangential element…. I am interested in Kallenbach for other reasons. I think he is more important in Gandhi’s life than most accounts have made clear. I think those letters which nobody had dealt with at length, but have been around for 20 years are quite remarkable and deserve a close reading and that is what I tried to give them.… I raised [these questions] but not with the sexual business in mind. I did start my discussion on that point because it was more than in the air, you know. It had been written about tangentially by some scholars and I heard it discussed a lot. But I also concluded my discussion in a page and a half by saying that let’s look at what they actually said and then have a fat paragraph on everything they do to remove aphrodisiac foods, that they deem to be aphrodisiacs from their diet and their comments on the need to resist physical urges. That’s where I thought I left the discussion. But most people didn’t turn that page. They read the previous page and thought that I was insinuating that Gandhi was gay, but that was not in my mind. Does it say something about the state of our media and the Internet that amplified the controversy in that form? Well I think so, but it is not India’s media or the Internet. It is the world we all live in. To take a much bigger example, was Obama born in this country? It has been clear, that he was, for years. But the thing floats around. Well this is a tiny example. In a way the controversy is over. Maybe I am being naïve, the book has been published in India, it is selling well in India, people have read it, there are number of positive reviews in respected Indian journals. People have a much better idea of what the book is about and what is actually in it than they did originally. I stopped reading comments online when I was scrolling down through the Amazon website where you have the customer reviews and a man named Dasgupta said that the book reflected a burning hatred of Gandhi and then 240 people voted on that proposition and most of them agreed that the book had a burning hatred for Gandhi. I don’t believe that it is possible to hold my book in your hand for a minute and come to that conclusion. So I assume that most of those people didn’t bother to read the book. They looked at the reports on the book. I have gotten emails from people who take issue with what they think I have said and they quite frankly declare, of course I haven’t looked at your book but I think it is entirely wrong of you to assert this and that. I don’t know whether to respond to such irresponsible emails or not. Now as a journalist you had to anticipate that this would be treated in this sensationalistic form. I didn’t. At that moment I wasn’t thinking or had thought about the Indian audience. As a journalist I am trained not to worry about whether people will think something is positive or negative. Once you start worrying about how various groups will react to what you are writing you become partisan. You soften it here and soften it there. My whole training as a newspaperman is to just get the story out as clearly and as cleanly and truthfully as I am capable of doing. So, I have to tell you that I didn’t think of those pages as controversial at all. They wouldn’t be controversial if we were talking about a relatively contemporary American figure, because we are used to discussing about the libido and debating about them. Let us examine the substance of the relationship that you do discuss in the book. I read the section and it is not clear to me what you concluded was the nature of the physical relationship between the two? I didn’t conclude basically. I meant to imply … let us not speculate, but let’s look at what they actually said, that it was celibate and that Gandhi was not a hypocrite. It’s not beyond possibility when you think of Gandhi’s later(what’s known about his massages and things like that) it is not beyond possibility that they, in their different approaches to physical fitness, that they had some physical contact — that they stretched each other, who knows what, but I don’t think it was sexual. There’s an American scholar James Hunt who I quote who used the term homoerotic, which is an actual term, and he is using it correctly, which does not imply sexual acts, but implies an attitude. I am not willing to go that far, because I don’t think I am qualified to go that far. I am not a psychoanalyst.… I have not given that a lot of thought. My attitude is how can we know and how does it matter, it was in their heads. We have a right to wonder what Gandhi actually did, because he proclaimed himself a brahmachari and I believe he was a brahmachari. It may have been a struggle for him at different times of his life, we know that. But that does not seem to me news or a great revelation. It’s been discussed a lot more loosely in various places than it was by me. You quote a Gandhi scholar as saying they were a couple. What did he mean by that? It is a very commonsensical and ordinary thing to say, that they lived together for nearly four years. Gandhi wrote that very amusing contract about what their relationship should be. There was a lot of teasing on that. We only have Gandhi’s word, he did a lot of teasing. When Kallenbach goes off to Europe he sends him a note about not looking at any woman lustfully. It is clear that they were intimate, but by intimate I don’t mean sexual and if you read the 12 pages or so that I wrote about their relationship, when I come to Kallenbach’s diary, which I looked at in Sabarmati Ashram, I noted he always referred to Gandhi in the diary as Mr. Gandhi and I said this makes it clear that it was not a relationship of equals. But Gandhi’s attachment to Kallenbach is also made clear by his repeated efforts to persuade him to come to India with him and he means for the rest of his life, he says as much. The fascinating thing when he pulls up the stakes at Tolstoy Farm and ships his things back to Phoenix, he ships Kallenbach’s books and tools too and Kallenbach then writes him and asks him to return them and Gandhi is a little wounded. He does return them, but he still trying to prevail upon him to come to Phoenix and come to India. And in the end that is what Kallenbach decides to do and if it was not for World War I this is what he presumably would have done. The core of the issue centers around the letter of Sept. 24, 1909. You make a point in your discussion that you can make selective picks and come to a conclusion.

You can accuse me of having it both ways. I build a case and then I step away from it. I actually made a change that will go into any later editions, because I got a letter from a Gandhi researcher who said the Vaseline (it is the reference to Vaseline that upsets people, it’s Gandhi’s reference) it remains mysterious to me suggesting massage and anemas as a possible explanation. I was referring to things that were later important to Gandhi in taking care of himself. Of course Vaseline has a thousand uses and somebody wrote me a letter pointing out another letter where Gandhi talks about having taken Kallenbach’s shaving kit to London and the suggestion is that Gandhi shaved with Vaseline. Well I haven’t heard of anyone shaving with Vaseline. But then I looked around on the Internet, matching Vaseline with shaving and in fact it was a practice. Maybe that’s the answer. What if the letter didn’t say Vaseline, what if it said shaving cream? If you take that letter and we remove Vaseline and enter shaving cream, it is still something of a love letter, it’s an unusual letter. It seems to me unlikely, since he was persuading Kallenbach to practice celibacy, that he would make erotic references in his letters. I agree with that completely. But it shows the nature of their conversation. He wouldn’t write a letter like that to Nehru or any of his other close associates. It just has a different tone, whether it is erotic or not, then you get into a discussion of well what do you mean by erotic? That’s where I want to step out of the discussion. It seems to me you can argue both ways. It it is a side issue and not very interesting, once you decide they were celibate. I found somewhat peculiar your discussion on Gandhi’s reference to his body being possessed by Kallenbach. The reference is preceded by a discussion on using a handkerchief as opposed to a torn envelope for blowing his nose and he seems to be referencing that commitment. I read it in reference to everything that came before. There were several points in that paragraph. This is something of a culminating point. You are right, it is an innocent reference. You can say, I am having it both ways. I am saying that selective quotations can build a case that caricatures the relationship so it appears to be sexual and I am demonstrating that, but then I say stop and say look at what they actually said. So my conclusion is that para on the next page that talks about diet and resisting physical urges. You question whether Gandhi said ‘Hey Ram’ when he died. One would think that journalistically you would dig deeper, even though I know it is difficult to come to a conclusion after all this time. None of the first references, none of the early reports said anything about last words. And the number of people who purported to have heard anything is fewer than 10, about 5 or 6, none of whom are available to talk to. I am satisfied to be agnostic on that question. To me, it appears unlikely that in those seconds he could have uttered those words that he hoped he would utter and to me it also appears obvious that despite what he said about uttering those words, it does not affect his status as a Mahatma. He set that test for himself and if some of his closest adherents choose to believe that he passed it, that’s fine with me. I cannot get there, but I don’t mean to say that it didn’t happen. I don’t know. I just laid out what’s on the records. I don’t know whom I could interview and what I could read that I haven’t read that would clarify. In some ways, I think the mystery of that instant should be allowed to remain a mystery and if the bulk of Indians choose to believe that this is how Gandhi’s life ended, I will not be the one to say it is not the way how Gandhi’s life ended. You don’t think you could come to a more definitive conclusion, or that you could probe it any further. I was not interested in coming to a more definitive conclusion and I don’t think it is possible in any obvious way. That is not what I was doing in those pages. I really doubt whether it is possible. I was just pointing out that this belief exists, what it is based on and that it is not unanimous. It also feeds the ambivalence that you want the book to capture. I don’t accept the word ambivalence. I think he was a very complicated, interesting person. I admire him for reasons that I can easily declare. I admire him for his constant striving for selflessness and for his moral seriousness throughout his life. I admire him for his identification with the poorest people, which is all too rare in modern life and I can think of no prominent political figure who is on a par with him on that. So for me there are plenty of reasons to revere Gandhi and whether or not he said “Hey Ram” is not one of them. Did Gandhi originate the ideas about civil disobedience and nonviolent struggle or did he just practice them more dramatically? There were the suffrages of London whom he was aware of. There was the writing of Thoreau, but that was an individual thing. I think the mass struggle, when he leads the strikers across the borders between Transvaal and Natal in 1913, it seems to me he is doing something that had never been done before and that remains an example. It becomes a model. The Salt March becomes a model. The Freedom Rides, some of the Civil Rights marches in this country and the idea of non-violent resistance and struggle — it goes beyond civil disobedience — is Gandhian. I was struck in your book by how much he had subordinated the political campaign to his personal and spiritual and social quests, especially in last years. It is even more so than I wrote about, because this is not a complete biography, I was following a particular set of issues. In the first half of 1946 he devotes himself almost entirely to setting up an institute in Pune for nature cures and all his energy goes into that and he is not much involved in the political negotiations going on in New Delhi. He does that sometimes. He just dives into something he is passionate about. What would Gandhian mean to Gandhi? I think I show that he devoted much of his own life to following his own agenda, what he called a constructive program. It wasn’t a big success, but it was a repository of a great deal of his energy. These weren’t just words, he actually attempted to live by his words. Think of Gandhi in 1936 settling in Wardha, which is far away from anywhere by most Indian standards at that time. Here he is practically 70 years old, world famous, everyone acknowledges he is the leader of the country, and he goes to settle in a village. It’s touching, it’s not very political, but it’s consistent with what he said all along he meant to do. It is just like what he did in South Africa when he founded Tolstoy Farm. It’s a recurring pattern in his life. I don’t mean to take it any further than that. I am not trying to construct a different Gandhi. I am just trying to show what he actually did in this area. Most people, including Gandhi’s supporters, are chasing his shadow, I think you used the word “nimbus.” He probably needs more protection from his supporters than his detractors. He said that once. But he is a very complex figure and people are going to keep writing about him and thinking about him. Nobody will have the last word on Gandhi. There will never be just one version of Gandhi, because he is is constantly changing. I find him amazing in the way he has these major points of reinvention every couple of years. That pattern starts really around 1900 and never quite stops. I guess it says something about our times too that nobody could get away with Gandhi’s experiments these days. Just think of the Noakhali tour. If it existed today, there would be camera crews, it would be on the internet. In fact it never got much publicity beyond Bengal. — Achal Mehra

|