Magazine

Indian Independence And The African American Struggle

Indian expatriates in America shared a common cause with African American leaders before Independence.

When Enuga Reddy arrived in the United States in 1946, he was an Indian man caught in the limbo of a country firmly divided between white and black.

Reddy, a scion of the Indian freedom struggle who moved to New York to pursue his graduate studies, quickly joined other Indians in a wider call for human rights, particularly for African Americans. Welcomed by fellow Indian expatriate-turned-global rights activist Kumar Goshal, Reddy became involved with groups such as the Council on African Affairs, an African American group dedicated to fighting against colonialism and exploitation of black and brown people across the world. By then, Indians in the United States had already managed to win support for Indian independence, as well as the greater rights of Indians in pre-Apartheid South Africa, because of the respect Mahatma Gandhi had engendered among blacks and whites. “African Americans felt very happy that Gandhi, a colored man, had stood up to Britain,” said Reddy, who stayed initially at the International House in New York’s West Side. “There was a feeling of kinship in the struggle.”

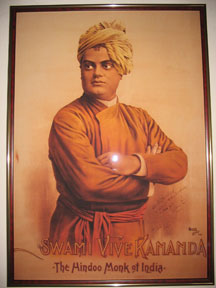

Reddy and Goshal weren’t the only Indians active in the human rights struggle during the 1940s, and they certainly weren’t the first. Indian expatriates, driven by a desire for equality and emancipation from European domination, had for years shared common cause with African American leaders. Lajpat Rai, Taraknath Das, Swami Vivekananda and Vijayalakshmi Pandit were just a few of the Indian luminaries who had visited America and developed kinship with the African American struggle for human rights. Others such as Reddy and Goshal stayed in the United States, serving as liaisons between blacks fighting segregation and Indians fighting for freedom in India and in South Africa. Though the Indian presence in the United States prior to 1965 is easily overlooked, their interaction with black and white human rights advocates, is an important part of American civil rights movement and the larger struggle for global suffrage. It also underscores the reciprocal feelings of kinship felt between Indians and African Americans as a result of a shared struggle against racism and oppression.

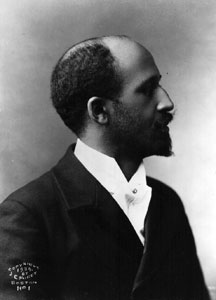

As the iconic African-American scholar W.E.B. Du Bois wrote shortly before the end of World War II, “I am not at all sure how much American Negroes know about India or realize the great fight that Indians, as well as African and Asiatics, are making for recognition in the modern world.” Roots of struggle and kinship Because of racial discrimination in the United States and the difficulty of Indians living under British rule to travel, only a handful of Indians came to the United States in the late-19th and early-20th century. The most famous visitor was Swami Vivekananda, who toured the country in 1893 while spreading the word about Hinduism and Vedanta philosophy. Vivekananda experienced overt racism, particularly in the South, where he was often confused for an African American. Some blacks also believed Vivekananda was a “distinguished Negro,” and in one case, a black porter congratulated him for representing black people so well. Vivekananda’s empathy with blacks extended to his teachings in the United States about Vedanta philosophy, particularly the need to dissolve the barriers that prevented different groups from rising together. When one of his followers asked why Vivekananda never corrected people who mistook him for an African American, he replied angrily: “Rise at the expense of another? I did not come for that.” Nearly two decades after Vivekananda, Indian freedom fighter Lala Lajpat Rai visited the United States and likened the African American civil rights struggle with India’s. Rai became close with Du Bois, who had become actively interested in how Indians were resisting white domination.

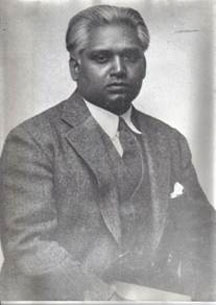

Rai left the United States in 1918, but continued a close correspondence with Du Bois until Rai’s death in 1928. In a book Rai was planning to write about British mistreatment of Indians, he asked Du Bois for information “about the treatment of negroes in the United States” and “the cruelties inflicted on your people by the whites of America.” Du Bois would later write about Indians’ ignorance of blacks, lamenting that “unless they are as wise and catholic as my friend…Lajpat Rai, they are apt to see little and know less of the twelve million Negroes in America.” By the 1920s, Taraknath Das, an Indian freedom fighter settled in the United States, had also made the connections between African Americans’ calls for equality and Indians’ desire for independence. Das, who became one of the pioneers of the Indian community in the United States and a benefactor of future Indian graduate students in America, aligned himself with numerous causes supporting African Americans.

Das later became friends with leaders of the Black Left, including Du Bois and the actor-turned-activist Paul Robeson. Das’s involvement with African American causes paved the way for other Indians to join forces with blacks during the Jim Crow segregation era. Indians on the frontlines of the struggle The few Indians who came to the United States as students or lecturers found it impossible to avoid the country’s racial conflict. In many cases, Indians were treated the same as blacks, and in the South, were often forced to ride in segregated train cabins and use facilities for “coloreds only.” One of the mainstays of the American Left from the 1930s to the 1950s was Kumar Goshal, an Indian revolutionary who fled to the United States to escape arrest by British authorities. According to Reddy, Goshal was involved with Indian militant groups who often used violence against British targets as both resistance and propaganda against colonial rule.

Though not much is known about Goshal, he made his mark almost immediately after reaching the States, joining a theatrical troupe in Chicago before trying his hand at writing. Goshal wrote two books, People of India and People of the Colonies, and at the height of the “Quit India” campaign, served as a correspondent for the African-American newspaper, the Pittsburgh Courier. Goshal’s articles about India often stressed the commonalities between Indians and African Americans in their struggle for human rights and independence. By the 1940s, Goshal had moved to New York and joined with other Leftists in the Council on African Affairs, a fiercely anti-colonial organization with unofficial ties to the Communist Party. He also taught at the Jefferson School, a well-known Marxist institution in Manhattan. Esther Jackson, a former acquaintance of Goshal’s during the 1940s, recalled that Goshal was keen on developing a social network of minority intellectuals against global oppression and that his writing often hreflected those beliefs. In many ways, Goshal was a precursor to Desi postcolonial writers such as Homi Bhabha, Arjun Appadurai and Gayatri Spivak. Reddy met Goshal shortly after he arrived in the United States. “He was not very friendly with the Indian community; his friends were in the left,” said Reddy, who recalled only meeting one other Indian at Goshal’s home. “As I was interested in the South African passive resistance, he suggested that I go to the Council Library.”

Reddy and a few other students joined African Americans and African students in protests against racial conditions in South Africa, where Indians had been stripped of their landownership rights. In November 1946, as the United Nations was set to take up the issue of South Africa’s treatment of Indians, the Council on African Affairs sponsored a rally calling for greater sanctions against South Africa. “I participated in it with an Indian woman student from Bombay, Ms. Anasuya Godiwala,” said Reddy. “We were very few Indian students at the International House then.” A short time later, Vijayalakshmi Pandit visited New York, pledging solidarity with African Americans against Jim Crow. Du Bois and other African American leaders, including Walter White of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, were among Pandit’s biggest admirers.

“She is a charming woman in every way, physically beautiful, simple and cordial, and she represents as few people could, nearly 400 million people, and represents them by right of their desire and her personality, and not by the will of Great Britain,” Du Bois wrote. Pandit made frequent visits to African American groups during her several trips to the United States. However, Du Bois remarked later that Pandit, who had called for an unconditional end to racial segregation in the United States, shied away from strong condemnation of the U.S. policy during the 1950s, a period when both the American and Indian government sought to establish closer diplomatic ties. Cooling ties during Cold War By the mid-1950s, most of the Indians who had come as students and as activist visitors had left the United States. The few who remained in New York settled in Harlem, sometimes marrying blacks and Puerto Ricans in the area. Felipe Luciano, a noted Latino activist, said that the social relationships between Indians and Puerto Ricans in Manhattan and Queens often arose from a common sense of economic disenfranchisement. Indian merchants maintained a small presence in New York during the 1950s, but de facto discrimination often prevented upward mobility.

By the end of the 1950s, the activist sentiment that had brought Indians and African Americans together had faded, replaced by individualistic ethnic and racial interests. Reddy noted that some Indians also harbored racist attitudes towards African Americans, choosing not to socialize with the group they had once worked alongside. “There was some racism among Indians,” said Reddy, who settled in Manhattan and began a long career with the United Nations. “Some people brought over their attitudes from India.” Reddy, who went on to become the assistant secretary general of the U.N. and led the U.N. Centre Against Apartheid, said that even Indians with strong political sympathies with African Americans rarely intermingled with other minority groups. However, the diminished ties between Indians and African-Americans, which were further strained following the immigration of Indians into the United States after 1965, should not discount the impact of their solidarity in the first half of the century. The Indian freedom struggle undoubtedly influenced African American leaders who saw kinship with a group determined not to let go of its identity.

As Robeson so eloquently noted nearly 70 years ago: “The struggle of the Indian people, their courage, the emergence of leaders like Nehru, give the lie to tales of a hopelessly backward people of a decayed culture … and there is one thing it seems to me we peoples of long oppression must remember: We must not be talked out of our heritage.” |