Life

Golgappas Meet The Gap

Moving with the times

| “You are no longer my son.”

Here is a stinging turn of phrase that transcends all physical and cultural margins. To this day, I vividly remember hearing them first-hand from my mother at age 16. “You’re a disrespectful, spoilt Canadian brat,” she said, “who has forgotten his cultural roots.”

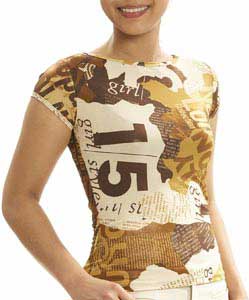

Weaned on Bollywood dramas from early childhood, ours was an inter-generational discrepancy of values – South Asian values, Hindu values, proper values. Contrary to her conviction and my vigorous dissent, I was affected. I am still struggling with my her observations on my identity. Mom’s accusations have led me to question: are my Eastern principles indeed battered by an essentially Western lifestyle? Better yet, does it matter? I hold a Canadian passport; why must I not embrace a Canadian identity? “My parents are, like, so mean!” It is a refrain I hear so often among my peers. I am therefore mindful that my dilemma is by no means unique. Nor is the habitual dynamic of parental dissatisfaction and youth rebellion unique to the South Asian diaspora. What is unique, however, is the mutually distorted expectations linking the first and second generation of desis. The former are people born and raised in Independent India. They embrace their culture and customs. There is an evident celebration of Indianhood, a pride in the history of its civilization. Their attachment to these traditional Indian values was palpable when Miss World 1994 Aishwarya Rai recently appeared on The Late Show with David Letterman. To a question by host Letterman if it is “common for grown up children to live with their parents in India,” Rai retorted, “Yes, I live with my parents.” “It is common in India,” she sassily added, “[since] one does not have to take an appointment to see one’s parent in India!” Such ethnocentricity thrives within the South Asian population. In fact idealized notions of culture contribute to the construction of ethnic identities. This is especially true for immigrants who have spent their formative years back home. They have already emerged from the turbulence of adolescence with a more or less affirmed sense of self. They know who they are. More so, they know their conception of home. Not that these concepts are written in stone. Nearly 60 years of independence have brought about enormous change. India is no longer simply affected by a history of colonialism. Rather, it is in midst of a phenomenon of potentially far greater bearing: globalization. On a recent visit back home, my brother and sister-in-law kindly gifted me a traditional outfit. “I wanted you to have something Indian,” my sister-in-law intoned. The intricate embroidery on the chiffon kurta appeared to be authentic Rajasthani work. Therefore, I did not expect to find the imprint of a designer logo on the tag. Apparently, Gap is now producing desi clothes for the desi market. And McDonald’s, never too far behind in matters of cultural appropriation, offers the McTikki Burger, a potato-filled fast-food option for a predominantly vegetarian Indian population. Incongruent, to be sure, for a nation fathered by Mahatma Gandhi’s notions of swaraj (self-rule). Defining the Indian identity, no doubt, transcends borders. So what of the Indian culture one finds abroad? Is it the Chai lattes served at a coffee shop near you? Or is it the pashmina adorned by your wealthy neighbor? Nor is it blindly adhering to the will of your elders, a cause of which my mother is foremost advocate. The key to grasping the situation is to acknowledge change. Traditionalists, such as my mom, refuse to comprehend a new Indian reality. This is the truth for that non-fanatical populace that sustains a sense of ethnic belonging, devoid of the conventional norms. Explicitly speaking, Indianhood is no longer merely about customs. Gone are the days when domestic girls and professional boys grew up in sheltered homes until their marriage was arranged for them. Shaadi.com now manages those affairs. Many in our generation have moved beyond these conservative rituals, into a broader, more liberal realm. Even back home, the Westernization of the Indian middle-class has been transforming. As a result, the roadside vender of foods and frolic has been displaced by shopping malls and nightclubs for those who can afford them. Beyond the Chacha Chaudhari novels, the Indian youth is now well acquainted with the heroic tales of Harry Potter. These kids are stepping out and, much to the disdain of some parents, exerting autonomy over their own lives. Indian kids in New York, London or Vancouver receive their dose of Indian culture through their parents, communities and specialized programming. They may not speak their mother tongue, but that is only a minor hindrance in the vibrant spirit of their culture. South Asian kids abroad are no less acculturated with their mores than those back home. They have been socialized in an assortment of belief systems and they often possess a greater appreciation for diversity, which allows them appreciate outlooks distinct from their own. If it takes a village to raise a child, why not let it be a truly global village? My Eastern principles are not battered, but, on the contrary, enriched by my Western lifestyle. Riding the public transit in downtown Toronto, I am exposed to cultures and counter-cultures in countless languages. Thus, my perception of Western society is not merely passed down through Hollywood blockbusters or quirky sitcoms based in New York City. Rather, I get to experience it first-hand through interaction with its masses. Second, I appreciate that my ethics do not require a passport. They transcend borders and, by way of such disposition, empower me to open my eyes to the world. At last, I grasp that I am being Indian the best way I know how: as a Canadian. There are choices to be made that challenge our established conservative norms. Premarital sex, interracial marriage and queer rights: they may resemble issues that are distinctly Canadian. But they are equally rooted in ideals of “life” and freedom” that inspired India’s freedom movement. The decisions ahead of us can be empowering, provided we find support in our homes. Wisdom, in the end, is not merely in having beliefs, but rather in having the courage to question them. The time has come to recognize that whom we love has no racial, religious and political boundaries. Let us understand that this is not about “them” – it is about “us.” As such, the true Indian legacy, although dressed in spring attire from the Gap, will eternally linger in our hearts. And maybe one day, a craving for golgappas on the bustling streets of New Delhi will lead us back home. All things considered, folks, we are all right. |