Books

Dark Truths From the Sunshine State

There is more to Goa beyond the sunny beaches and susegad. A secret past tradition that was deliberately kept under wraps… until a new book ripped off its lid.

Goa, a coastal state in Western India, has always been the shining beacon of modernity and excitement in an otherwise conservative country. The top tourist destination has consistently been voted as one of the best places to visit in India, not just by international visitors but also by Indians. A recent survey by online accommodation booking website hotels.com revealed that Goa was the most popular monsoon destination amongst Indians again in 2017. The popularity of this beach state is also enjoying a rise as the survey also revealed that the village Arpora in Goa, saw a whopping 91 percent increase in hotel searches as compared to the data in 2016.

And while in the past couple of years, international tourist inflow has been on the decline, Goa still remains one of the most frequented destinations in India for international tourists, along with Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Rajasthan. In 2015, 49,626 e-visas were issued for travelers to Goa, with Russians topping the list (25,770), followed by the UK (11,748), Ukraine (6,892) and Germany (1,113).

Goan Market Scene. Illustrations by Mario Miranda /Poskem by Wendell Rodricks

For years, the promises of cultural diversity, the preserved Portuguese past, beautiful beaches, colonial architecture, biodiversity and a rocking nightlife that has lured tourists to Goa.

There is also a dark side to this shiny state brimming with neoteric vibes. A side that locals for decades kept deliberately under the wraps — the tradition called Poskim.

Poskim (plural Poskem) is a Portuguese term used to describe young children from poor families who were adopted by rich families and made to live with them, even taking their family names. But the charity ended there. Most of these children were treated as house helps. Unlike other children in the household, they were not sent to school nor did they get any inheritance rights.

In a world where talks of equality and human rights are de riguer, this secret tradition in Goa is a grisly reminder of what bonded labor in the contemporary world can look like.

According to locals, the tradition is on the decline with rising awareness, concerns about child rights and also the changing attitudes of people. But the fact that it existed for years and even today many families have Poskim growing up in their midst is a grim reminder how caste and money could continue playing a role in societal divides.

Goan Aristocrat Family. Illustrations by Mario Miranda /Poskem by Wendell Rodricks

Rodricks admits that this may be the last generation of Poskem and has heavily relied on his observations, anecdotes from his mother and other elders who knew and experienced the tradition first hand. The accounts and the stories in the book are real, but the author has fictionalized them.

But how is it in a state such as Goa, which has a flourishing tourism sector and boasts literacy rates of 87 percent, among the highest in India, nothing has been written before about Poskem. Rodricks minces no words in admitting that Goans realize that it is a shameful tradition and do not talk about it. Indeed, the stigma attached with the subject is so great that most Goans expressed shock on learning about his book.

In a country where exploitation of household help is commonplace, perhaps Goans were inure to the practice more than seeking to keep it secret. Rodricks demurs: “Everyone knew/ knows, it is a shameful tradition. But Goans don’t want to talk about the Poskim. They feel that it is a dark secret best left unspoken about.”

However, times are changing and the younger generation especially finds the practice inhumane. Rodricks says: “When I first disclosed that I was going to write Poskem, they (the locals) were in disbelief that one would approach such a subject. Many would ask ‘But what is there to write about these people? They were adopted children. That’s all.’ Imagine, these stories would never have been told until I created the characters and wrote Poskem. There are Poskim till today in Goa, but I hope after the book, this tradition stops and this derogatory word is not used again.”

Origins

How did the practice of adopting children from poor family and then treating them like servants came about ? Damodar Mauzo, Sahitya Akademi award winning novelist and scriptwriter from Goa, says: “The tradition of adopting Poskemi must have started with good intention. The poor members of the family clan would expect the well off from their own caste to look after their child. The bhatkars (landlords) with a philanthropic bent of mind generally obliged. In some cases, when a couple did not conceive for a long time after their marriage, they would adopt a child from their less fortunate kin, with a hope that the adopted child may bring in luck to them. Often, they would later conceive and then their love would shift entirely to their own child thus leaving the adopted one to face negligence. Though there are cases where the Poskim were fortunate to get decent living, the unfortunate ones outnumbered the fortunate ones.”

Street in the Latin Quarter of Fontainhas, Panjim. Illustrations by Mario Miranda /Poskem by Wendell Rodricks/Om Books

The tradition passed from generation to generation. Rodricks says: “I heard about the Poskem from villagers. I imagined them to be servants as they were treated as such. Later my mother explained that they were poor children adopted by families to work at home (for the most part). I found it shocking that they were given the family name, but not allowed the privileges of the other children in the home. Sometimes they were not allowed to marry, nor given a proper education. They rarely got a share of the family inheritance. Many were abused to a life of bonded labor.”

Perhaps the locals realized this unfairness and were therefore careful of not bringing the practice into the open. Before Rocrick’s book very little was known publicly about the Poskem in Goa.

Mauzo adds: “My guess is that the concept of Poskem came into being during the Goan exodus following rampant conversions and later the enforcement of ecclesiastical law of Inquisition. The missionaries probably encouraged the adoption of orphans left behind by the distressed parents. This may be the reason why this tradition did not prevail outside Goa.”

One of the very few people who had highlighted this practice earlier is Goa based playwright Isabel Santa Rita Vas, who acknowledges that she has always known about the adoption of children as domestic workers, since it was a fairly common practice in Goa. She says: “Back in 2000 I wrote a short piece called, ‘Poskem or child of the heart?’ for a column titled ‘Pass the Mustard, Please’ that I was doing for a local paper, The Herald. It dealt with the theme of adoption practices in India. I touched upon the practice in Goa of adopting a child, generally a girl, basically for domestic work — the poskem (Konkani) or the crioula (Portuguese). I quoted a pastoral letter from the then Portuguese Patriarch in Goa, Jose Alvernaz, who wrote in 1946: “It is sad to note that, in certain civilized circles, practices of slavery in disguise should still persist, and that one should deny to one’s subordinates inalienable rights like to marry and have a family. It makes no sense at all that we should preen ourselves as modern, that we should preach so many freedoms and claim them for ourselves, that we should believe we possess a high degree of social culture — if, we simultaneously turn into oppressors of our subordinates and deny them a minimum of freedoms to which they have an undisputed right.”

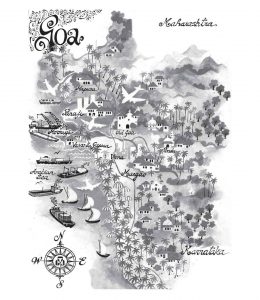

Goa Map. Illustrations by Mario Miranda /Poskem by Wendell Rodricks/Om Books

Ignoring the Obvious

Rodricks owns up to the practice: “I am ashamed to say there were Poskim in our family history. Though we were friends with them, we knew from the onset that they had a different place in the family and were technically not to be treated as family. They did not sit at table with us at mealtimes, did not sit near us in church, spent most time in the kitchen, did household chores, did not go to school and were always in the shadows, away from our comparatively privileged lives. The worst part was that the entire village called them by that dreaded name. Girls were called Poskem, boys Posko and collectively they were called Poskim.”

Since the practice was concentrated in specific areas and sections of society, not much about it was known to the outside world. Goa based historian and author Fatima Gracias, who has extensively researched Indo-Portuguese history and authored several books, says: “The tradition of Poskem was not a widespread one. It existed amongst certain families in Goa, mainly, among Christian families. Hindus in Goa also adopted a child when they were childless, usually from within the family — a male nephew or cousin.”

Gracias adds: “Goans and many in the Goan diaspora are aware of this tradition, even though some in the younger generation may not know it by the specific name (poskem for female and posko for male), but just as an adopted child.”

There were also darker reasons families resorted to the practice, Gracias says: “Sometimes the child was the illegitimate child of the member of a family and was sheltered within the family.

Goa based writer and a keen observer of the Goan life, Cecil Pinto says although the Poskem tradition may be passing, it is reemerging in other forms.

Childless couples adopted a poskem or posko. At other times they were adopted with the ulterior motive of engaging them later in life in menial work, taking care of the house, elderly, fields, property, etc. They received no remuneration for their labor, except for food, shelter and basic necessities. They enjoyed no legal rights of a biological child and were usually acquired from a single mother or poor parents after providing them some kind of compensation.”

Goa based writer and a keen observer of the Goan life, Cecil Pinto says although the Poskem tradition may be passing, it is reemerging in other forms:

“I don’t see the poskem tradition much, but another form of the ‘tradition’ is prevalent. Young men and women, mostly from another state, are brought in as household help. They are paid a miserable salary on the grounds that they are getting free food and accommodation.Now some may call this exploitation, it is debatable. They are free to leave, but then they usually don’t have anything much better to go back to in their home state. And some families treat these hired helps quite well and sometimes even allow them an education and later help them get married etc. It is worthy of a study.”

Damodar MauzoDamodar Mauzo lived and worked all his life in Goa and saw this tradition from close quarters. This tradition that got started with good intentions lasted for centuries. However, the drawbacks of the system did not encourage people to allow their child to give for adoption as poskem. The poskim were often maltreated and abused, of course, depending upon their embraced parents. I know of poskim who were given education, married off and even given share in property. Those with good intention would adopt the child legally and those who wanted the child to slog for them did not. Secondly, the poskem always carried the stigma of being called Poskem, even publicly. With the spread of education and the awareness of democratic rights, the system has gradually died.

I can site an example. A bhatkar couple in my neighborhood was childless. They adopted a girl from a poor family, clearly with intention of turning her into domestic help. This poskem, though was enrolled in school, would perform all the household chores and hence had little time for her studies. Later, when the couple realized that she may not be of any use to take care of their property matters, they adopted yet another boy. The boy’s family made it clear that he should be legally adopted as their son. Later, the boy, who got good education, got married and started living separately, as is the practice among Goan Catholic families. The couple who had grown old by then did not show any intention of marrying the girl off. The high school educated poskem when she entered her thirties, realized that she would ruin her life and wisely found a suitable boy for herself. The old couple was unwilling. But the social pressure compelled them to accept the proposal. But before agreeing to marry her off, the adopted son took her written consent that she had no share in the property. The girl is now happily married though continues to live a not-so-poor life. This is a happy story for the posko boy; but not-so-happy one for the poskem girl. |

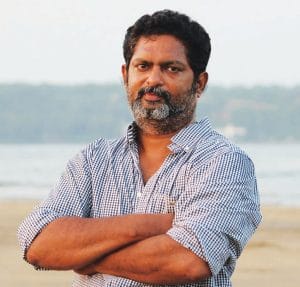

Wendell Rodricks on why he wrote his bookWhen I moved to live in Goa in 1993, there was a Poskem called Rosa who lived opposite me. Living alone in large houses, we chatted with each other across the street and became friends. We sent food to each other and enjoyed brief conversations. I think Rosa was surprised at my kindness. Neighbors told me she was a Poskem and they treated her in a condescending manner, as if she was not of our intelligence…which I found bizarre. Rosa was completely sane. Maybe she did not have a complete education but she knew to read, write, was baptized and lived a Catholic life.

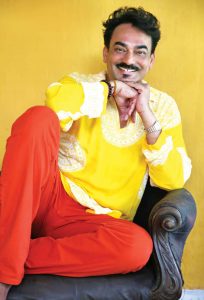

Wendell Rodricks. Photo : Francois Matthys She looked after the house and lived in her own lonely world. Rosa did not ever see the interiors of my home. If I called her for a cup of team she would say “But you are a bhatkar (landlord). I am too small a person to have tea with you.” That pained me. When Rosa died, I promised at her coffin that I would write about the Poskim — the forgotten Goans in the shadows. I dedicate the book Poskem to Rosa and the Poskim people of Goa. In today’s world of human rights, this tradition will die a natural death. In my village, there is only one Posko that I know about…since Rosa. Now that some Goans know that the book will be out, they are already distancing themselves from the tradition. North Goa people say that the tradition exists in the South. And vice versa. I find it amusing that they want the stigma of Poskim to be kept away from themselves. Yet some still have Poskim in their homes; though they deny this fact. |

1 Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment Login