Arts

Celluloid Man: Past Without History

For Nair, the very existence of the past, even in its residual form was more important than constructing a discriminating history of cinema.

“You can see a hundred years from now; you can see a certain aspect of life which was there only at the time, on that day. It means a lot. It means more than Greek Tragedy where everything is heightened beyond compare. But those very small things get so beautifully manifest (on film). It is the very, I think, soul of art of any kind.”

-Kumar Shahani

For anyone who has spent time on the campus of the Film and Television Institute of India in Pune and visited the National Film Archive of India only a couple of blocks away, it is impossible to not think of the omnipresent influence of P. K. Nair, the long-serving director and founder of the Archive. If you were there for films, then the purpose of your existence depended on the generosity, judiciousness and genuflecting command he exuded through each of his gestures. When you asked him about watching specific films, he would either point to a schedule posted outside the Theater or make one up in his own mind. He had the films and the will to screen them in the FTII Theater. He held the keys to everything possible and permissible. His powers opened up opportunities and defined them as well. Watching Nair walk across the campus with the mysteriously prohibitive reels of Kubrick’s The Clockwork Orange (1971), flanked by staff members and the projectionist, was watching privilege and access in action. He was both authoritative and generous. Nair was cinema for decades on that campus which formed the intellectual and artistic vanguard for Indian cinema. Everyone remembers him and all owe him something. With his will to power, he shaped the taste of generations of filmmakers, cinematographers, editors, actors and actresses, film teachers around the country and cineastes who turned into cinephiles.

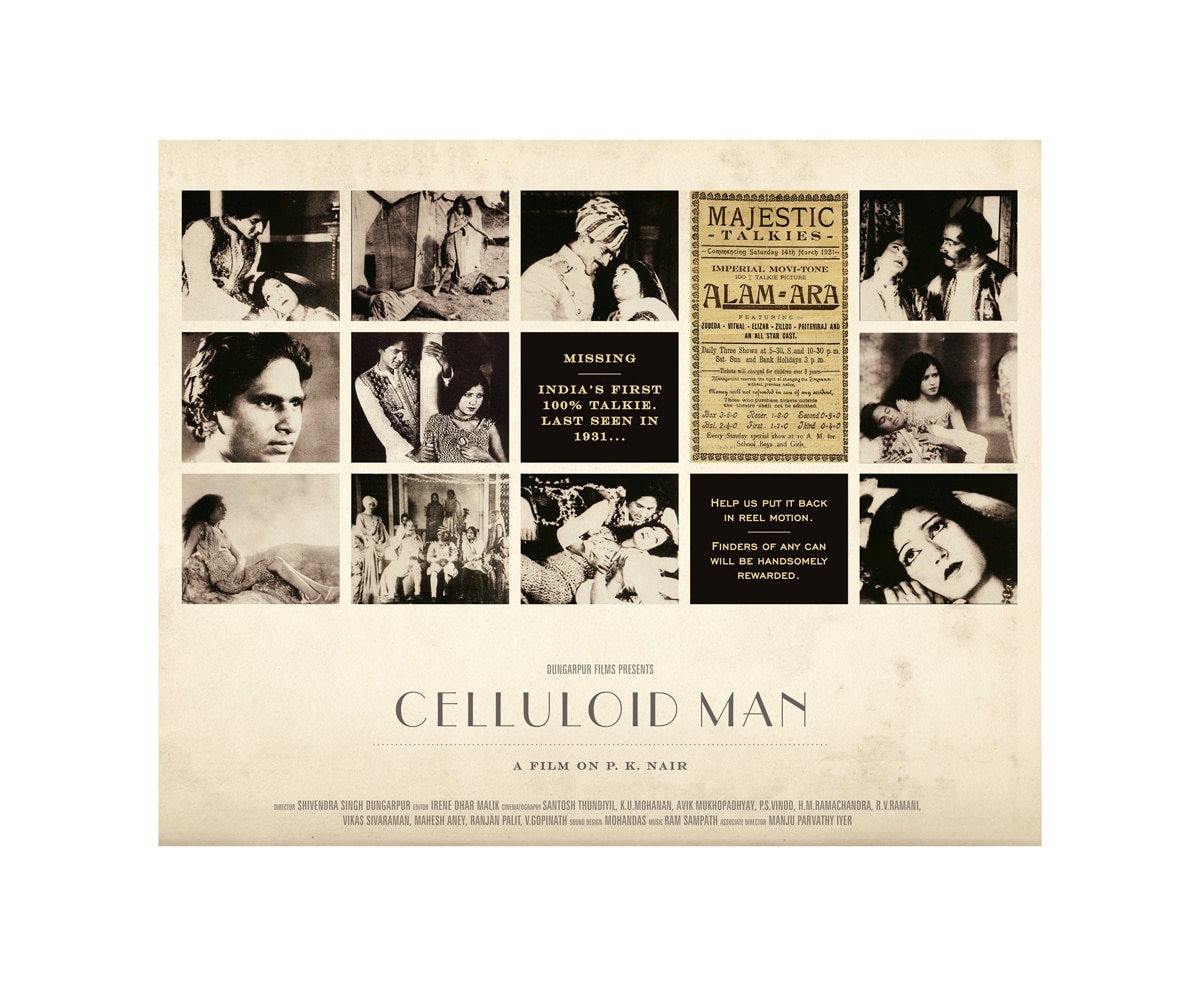

As Nair watches the world go by from his front porch literally feet away from the gates of the Institute and on the path from the nearby Archive, India pauses to mark 100 years of cinema, one of the many centenary moments it has marked over the past decade. But May 3rd marks 100 years since the release of the first film made by Dadasaheb Phalke (Raja Harishchandra), a film rescued in 1969 by Nair from Phalke’s son in Nasik. Within its first five minutes, Shivendra Sing Dungarpur’s film on P. K. Nair, Celluloid Man (2012) recounts Nair’s visit to Nasik to recover “bits and pieces of Kaliya Mardan (1919) (“the only complete film of Phalke’s film in the archive at the moment”). For three decades, Nair worked painstakingly to acquire films from various regional cinemas, often traveling to remote places, discovering them in unsuspecting corners of the country. It is fitting that on May 3rd, the film receives its theatrical release in India, hopefully reminding people of the example that Nair has set and the history that Phalke opened up for cinema in India.

As Nair watches the world go by from his front porch literally feet away from the gates of the Institute and on the path from the nearby Archive, India pauses to mark 100 years of cinema, one of the many centenary moments it has marked over the past decade. But May 3rd marks 100 years since the release of the first film made by Dadasaheb Phalke (Raja Harishchandra), a film rescued in 1969 by Nair from Phalke’s son in Nasik. Within its first five minutes, Shivendra Sing Dungarpur’s film on P. K. Nair, Celluloid Man (2012) recounts Nair’s visit to Nasik to recover “bits and pieces of Kaliya Mardan (1919) (“the only complete film of Phalke’s film in the archive at the moment”). For three decades, Nair worked painstakingly to acquire films from various regional cinemas, often traveling to remote places, discovering them in unsuspecting corners of the country. It is fitting that on May 3rd, the film receives its theatrical release in India, hopefully reminding people of the example that Nair has set and the history that Phalke opened up for cinema in India.

The film screens at the International Film Festival (IFFLA) in Los Angeles on April 14th. All the cinephiles in L.A. should head out to Arclight Hollywood to watch the film and attempt to recoup both the sense of purpose of this archivist and a long mission ahead of us in preserving cinema.

Nair tells the story of his conquests to acquire films, one after the other, each a patient victory of passion over circumstances. From among 1700 silent films made in India, only 9 survive (not all in complete lengths), mostly because of his efforts. Precious clips from these films appear as rare gems, a gift incredibly rare, even if you managed to travel to the site of the film archive. Nair worked and developed his own barter system, seeking film after film, reel after reel, amassing a collection so the largest film industry in the world can have its own film archive. He worked in different times, when celluloid ruled and when the beneficently socialist ethics of most countries in the world allowed exchanges of films. At times, Nair bent the rules, copying prints on his own at his will, but mimicking a practice that was common among archivists at the time. If a film came across his way and his will matched the opportunity, Nair grabbed it. Dungarpur’s film is a tale of one man’s perseverance in a climate when no one realized the potential of preservation. Had it not been for Nair, few would have realized the archive’s importance for our understanding of cinema.

Adoor Gopalkrishnan recalls how the rich producers of Mumbai Cinema (Bollywood) never cared for holding on to the negatives. If film has brought them enough revenue, it was inevitably set for neglect or destruction. Yash Chopra admits his mistake of not sending many of his films to the archive. Mahesh Bhatt appears to have little interest in saving the past of cinema but fondly recalls how he found in Nair’s possession films made by his own father. Ramesh Sippy arrogates his admission that his blockbuster Sholay (1975) is still making money in theaters and is therefore not worthy of including in the archive. Sippy appears in a frame with a wall size poster of Sholay behind him as his leisurely posture powers over the camera held at a low angle. Nothing could have said more about the callous ignorance with which the moneyed class values the act of reflection and preservation.

For Nair, the very existence of the past, even in its residual form was more important than constructing a discriminating history of cinema. In an environment with plentiful resources, it may have been possible to establish a discerning taste in the archive. But in an industry that cared little for any record of its cinematic past, everything was grist for Nair’s preservation efforts. Filmmakers outside of the commercially successful circuit show up in Dungarpur’s films to show appreciation of Nair’s critical role in building the archive, in instilling some sense that past is worth preserving. K. Hariharan, Jahnu Barua, Saeed Mirza, Mrinal Sen, Shyam Benegal, Ketan Mehta, John Abraham and others.

Celluloid film is not merely pushed into the dustbins of history; it is at times destroyed once it reaches the margins of subsistence economy. Silver is extracted from the films to make bangles and other artifacts (remember what happened to Georges Méliès’s films!). In one of the scenes, we watch white strips of celluloid being dried, once silver has been removed from them, perfect symbols of an age in which those who have the means care less and those who don’t, care for something more fundamental. Art does not survive in the hands of the hungry but a culture’s worth is measured only by those who protect it. It is a heart-wrenching moment in the film. Add the horror stories we have heard from the All India Radio Archives about willful destruction of sound recordings, and you realize the monumental challenges faced by archivists.

Celluloid film is not merely pushed into the dustbins of history; it is at times destroyed once it reaches the margins of subsistence economy. Silver is extracted from the films to make bangles and other artifacts (remember what happened to Georges Méliès’s films!). In one of the scenes, we watch white strips of celluloid being dried, once silver has been removed from them, perfect symbols of an age in which those who have the means care less and those who don’t, care for something more fundamental. Art does not survive in the hands of the hungry but a culture’s worth is measured only by those who protect it. It is a heart-wrenching moment in the film. Add the horror stories we have heard from the All India Radio Archives about willful destruction of sound recordings, and you realize the monumental challenges faced by archivists.

U. R. Ananthamurthy says in the film “We have a rich past but a very poor history, whereas the West has a significant past. (Perhaps) Not a rich past, but a very significant history.” Dungarpur’s film and Nair’s life make an argument to write, to preserve and treasure the cinematic past of India. For a country that boasts of “shining” in front of the world, and claims to have the most prolific film industry in the world supported by the largest audience ever, the state of preservation is a shameful disgrace. Think of Celluloid Man as salvo in that debate that needs to be held. John Berger says in a different context that there are two ways to remain innocent in the current state of things. First, by remaining ignorant, not knowing what is going on around you. Second, one remains innocent by maintaining a willful distance from the conditions around you, neglecting the injustices that are perpetrated in the name of culture and conventions. It is time to decide one’s own image of that innocence.

Dungarpur’s film is mainly about Nair; film preservation figures as a principal activity engaged by its protagonist. This is not an investigative report. But there should be one. And when that takes place, let us also turn our attention to those who are complicit by remaining ignorant, by claiming innocence. Failure to act contributes to the gravity of the situation as does deliberate sabotage. Shabana Azami recalls how she spoke about the fire at the Archive in the Parliament and there was no response from the legislators for whom there are no largesse to be had in such causes. Film preservation is important all over the world but for a country that claims so much for its cinema and where money is being minted in the film industry, there must be some sense of social responsibility that results in something constructive.

The state of film preservation is as abysmal as the state of the FTII, another blot on our capabilities to do something meaningful in cinema. There are several images of the campus in this film that re-sketch on your mind-screen the fossilized existence that the space of the Institute has acquired. Little has changed over the years and that is not about the physical familiarity of the space but bureaucrats that still run it. When creative people are put in place, the rigid and corrupt bureaucracy hampers their work. No one ever sees the light at the end of the tunnel though occasionally blindingly bright lights appear when rumors of industry’s takeover of the Institute persist.

Dungarpur went through considerable amount of trouble to make the film, including Nair’s reluctance and the trenchant bureaucracy at the archive. This self-financed film is a testament to the deep affection that the filmmaker has for its subject. But it is easily eclipsed by Nair’s own life-long love for cinema. Nair agreed when Dungarpur decided to film in only in celluloid. Dungarpur embellished this gesture with the use of a variety of stocks, including 35mm, 16mm, color and black and white, 200T, 50D, 7222XX and 100ASA. Eleven cinematographers, all of them graduates from the Institute were used in the filming of the documentary. Combined with the footage acquired from past films, Cellluloid Man is a visual treat, a variety of cinematic shades assembled as a final homage.

Nair worked as a bureaucrat, steeped in the rules and paperwork, willing to push it as and when required. But at the other end of his contradiction, he comes through in this film and for many who have known him, a creative manipulator of his bureaucratic persona. He acquired films on his own, copied them on his own and bent the structure to suit his passion for preservation. He took upon himself the mantle of educating large groups of people. For the residents on campus, it was familiar to see Nair sitting alone in the theater, work on the steenbeck, sneak in a late-night screening and as Naseeruddin Shah recalls, gather up at his secret and quiet Saturday mornings review of “censored clips.” No one ever questioned Nair’s own decision making, partly because it was in the service of cultivating cinephilia. Those who value this unique combination of a bureaucrat and consenting co-conspirator will realize how rare his work has been.

Nair’s reminiscences of his own life are gentle and quietly delivered. Whenever we met him in early 1980’s, he had a consistent demand that there be an oral history collected from all the surviving artists of early Indian cinema. Now, Nair has produced his own version, and a precious one it is. His deeply pursued passion runs against his obligations as a family man and interviews with his daughter disclose a man completely separated from the pressures of his own responsibilities at home. Nair comes across as larger than life and the man deserves his place in the spotlight. Dungarpur spares no effort in making Nair appear as a romantically devoted fan of cinema, framing him in front of running images on the screen, or sitting alone in empty theaters (Nair’s own habit). His gait is unsteady, posture aged and eyes tired. He breathes cinema, reminding us of a time when we sat in front of the screens and waited for the image to roll. All the while, he was in charge of rolling them. Now that we have gotten the faux control of starting, stopping and moving images, we must return to guard the spirit of preservation that Nair pioneered and exemplified.

Nair’s reminiscences of his own life are gentle and quietly delivered. Whenever we met him in early 1980’s, he had a consistent demand that there be an oral history collected from all the surviving artists of early Indian cinema. Now, Nair has produced his own version, and a precious one it is. His deeply pursued passion runs against his obligations as a family man and interviews with his daughter disclose a man completely separated from the pressures of his own responsibilities at home. Nair comes across as larger than life and the man deserves his place in the spotlight. Dungarpur spares no effort in making Nair appear as a romantically devoted fan of cinema, framing him in front of running images on the screen, or sitting alone in empty theaters (Nair’s own habit). His gait is unsteady, posture aged and eyes tired. He breathes cinema, reminding us of a time when we sat in front of the screens and waited for the image to roll. All the while, he was in charge of rolling them. Now that we have gotten the faux control of starting, stopping and moving images, we must return to guard the spirit of preservation that Nair pioneered and exemplified.

Celluloid Man is a heartening accomplishment, especially considering the exposure it has received at the film festivals. But its audience needs to be larger, broader and more diverse. It is easy to applaud archivists at the festivals. It is more difficult to defend and praise them in theatrical viewing and in corridors of power. At considerable length of 140 minutes the patience it demands is little compared to what it represents. We need prodding of bureaucrats combined with ingenuity of passion to embrace whatever little imperfections films like Celluloid Man have. They dwarf in front of the challenges facing the age after Nair.