Magazine

Behind The Glitter

Behind the scene at the White House state dinner for Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.

|

The wall-to-wall coverage by the mainstream media of the exploits of Tareq and Michaele Salahi, the Virginia couple who crashed Pres. Barack Obama’s first state dinner at which he hosted Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, may have sucked out all the oxygen, but the handful of Indian Americans lucky enough to bag invites to Washington’s hottest party this holiday season are still basking in its afterglow.

Leading up to the dinner, political blogs buzzed with blow-by-blow accounts of what Politics Daily dubbed “the most sought-after invitation in Washington.” Politico, the touchstone for political junkies, commented: “If you thought landing a seat at the White House Correspondents’ Association Dinner or the Gridiron Club Dinner was tough, try getting the nod for the upcoming White House state dinner. It’s one of D.C.’s most coveted invites, and the guest list is expected to number about 400. Rest assured that politicos have been jockeying for a spot….”

In a reflection of just how far off the mark the mainstream media’s reporting of the event was, the invitation arrived innocuously enough – unsought and unannounced – in the mail in the form of a card embossed with the White House seal at the homes or offices of nearly 100 Indian American guests. Some, such as Bhairavi Desai, executive director of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance (NYTWA), received their pleasant surprise almost a month prior to the event. Others got theirs in the mail just four days before the banquet. Recalls Desai: “It was a nice surprise to receive the invite since we were not expecting it. It was also a great honor for our organization that the White House had acknowledged us and allowed us to bring the issues of taxi drivers to the highest state. Our own community recognizes business leaders, but not grassroots organizations, so this was a beautiful thing.”

The hoopla over the Salahis and the preening coverage of the ostensibly rich and glamorous by not just the mainstream, but also the Indian print and broadcast media, glossed over what was perhaps the most notable aspect of the guest list – the surprisingly large number of Indian community activist invitees, in a nod, no doubt, to Obama’s own activist background in Chicago.

Says Annetta Seecharran, of South Asian Youth Action (SAYA!), which mobilizes South Asian youth: “Social organizations are imperative to underscore the inclusive nature of the White House and the desire to completely reflect all of society. Obama is walking the talk.” Vinod K Shah, president of the American Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (AAPI), believes he came to the White House’s attention from his earlier communications with the administration on healthcare reforms: “I had written an elaborate letter to Obama about healthcare reforms and personally handed it to him when I was invited to meet him at an earlier occasion. Plus, I have been in Washington D.C. for 42 years so I have relationships with the Indian embassy.”

After recovering from the disbelief and excitement over being invited, many of them began focusing on their role as guests – what to wear and who to bring. There was the deliberation over the protocol: should one greet Prime Minister Singh and his wife with a Namaste or a handshake? Should one bring a bottle of wine or gift to the party? The questions were especially vexing for some of the community activist guests, who had never attended such a high profile event before. First-time invitees, like See-charran, say they were flummoxed by the invitation, which simply provided the time and venue of the event, but no additional details. Was it just a party or was she expected to also pitch her company? “I did think about policy issues and immigration reform before attending in case I got to talk to Obama or someone important from his administration,” says Seecharran.

Some guests, such as Deepa Iyer, executive director of South Asian Americans Leading Together (SAALT), a civil and political rights organization advocating on behalf of South Asian Americans, had attended previous White House events, including the Diwali ceremony in October. She says, “I have engaged with the White House on healthcare, immigration and other issues that have been weighing in the South Asian community decisions. But this invitation was a welcome surprise as it was a fun event. It shows us that the Obama administration has a good understanding of the community and wants to engage with well rounded people who can connect on issues beyond business and entertainment.” Most invitees were accompanied by their spouses, since they were given the option to bring a guest. Some, like Iyer, took a parent or friend, in Iyer’s case, her father. Urvashi Vaid, a gay and lesbian activist, was accompanied by her long time partner, the comedian Kate Clinton. The guests had to confirm their attendance by calling back a number provided on the invitation card, which directed them to leave their name, accompanying guest’s name and social security numbers on an automated voice message system. “I didn’t have any more information like what time to show up or how early for the dinner. There was no person in the White House I could ask to clear my doubts. But a few days prior they put a phone recording on what time to come in and what gate to come to,” says Seecharran.

The guests had to arrange their own logistics. Most out-of-town invitees drove or flew down to Washington, D.C., and stayed at hotels. For this “black-tie” event the sari was the outfit of choice for Indian women. Many female invitees said that a sari was elegant, conservative and appropriate for the occasion; besides where else would they get the high profile opportunity to wear their best outfit? Some like Desai wore a churidar, “I went to Jackson Heights in Queens and had the outfit tailored to my size.”

Once the guests arrived at the South East gate of the White House, they had to wait in long lines, made bearable by the chance to share the company of celebrities, such as Steven Spielberg and Jhumpa Lahiri, who all had to endure the same wait. After their identifications were verified, they were made to pass through metal detectors. Staffers then hustled the guests into the White House, where they checked in their coats and were announced into the media room individually with their guest to a bevy of flashbulbs. They then moved to the East Room for a cocktail reception where they mingled with other guests.

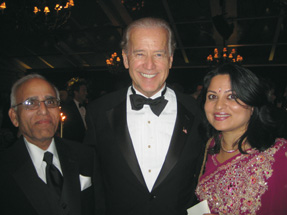

Next, they were ushered into the Blue Room, which, most agreed, was the evening’s highlight, where they were greeted in a receiving line by Pres. Obama, First Lady Michelle Obama, Prime Minister Singh and his wife Gursharan Kaur. The standard greeting from Obama to guests was: “Welcome to the White House. I hope you enjoy yourself. Thank you for the workyou do.” Most invitees, especially first-time visitors, said that they were too tongue-tied to respond with anything other than platitudes. But some managed to get in a political clap on the back or a dig. Progressive magazine reported that Vaid urged Obama to get tougher on the right wing. Iyer told the Obamas of her work to empower South Asians around the country on immigration and civil rights and thanked him for the invitation. Vishakha Desai, president of Asia Society, took the opportunity to invite the Obamas to Asia Society. “I’m sure they will follow-up,” she says. Maneesha Kelkar, director of Manavi, a domestic violence center for South Asians, says she thanked Obama for recognizing community activists, to which Obama responded, “You know I was an organizer too.” Seecharran was enamored by her encounter with First Lady Michelle Obama: “I was completely blown away. She was stunning and statuesque. She didn’t just possess physical beauty but had incredible warmth. She shook both my hands and said, ‘I’m so looking forward to getting to know you and your work.’ I thought I was going to pass out. I didn’t know I was so important.” Seecharran shared a table with Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal, but made a concerted effort to avoid policy talk, even though she had prepped herself: “I got a vibe that this was a party and a time to celebrate Indian accomplishments in the U.S.” The celebration reached a crescendo with Jennifer Hudson’s powerful vocals and a dance performance by the Bay Area Bhangra Empire, during which, several guests reported seeing even Prime Minister Singh tapping his feet.

Hotelier Sant Singh Chatwal, a powerful Hillary Clinton booster, who had a dust up with the Obama campaign during the presidential election, attended the dinner as a guest of New York Congressman Gary Ackerman. Chatwal, who was also a guest at the 2000 Clinton state dinner for former Indian Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee, says he was impressed at the Obama team’s effort to Indianize the event, includinga substantial vegetarian selection as well as bhangra performances and music by A.R. Rahman. He was equally enamored by Michelle Obama’s Indian-inspired gown (designed by Indian American fashion designer Naeem Khan) and “choodis” (bangles). Adds AAPI’s Shah: “It was a very unusual event. You felt good about yourself, India and Indo-U.S. relationships. I saw the warmth and mutual respect between the president and prime minister. People were made to feel comfortable so it gave the feeling not of being at a high profile event, but of being at a small get together of like minded people.” For some invitees the setup and ambience in the South Lawn was reminiscent of another time they had walked along the marble-tiled East Wing to greet a U.S. President and Indian Prime Minister. Asia Society’s Desai is among the few Indian American guests invited to all three state dinners – by Pres. Bill Clinton, Pres. George W. Bush and Pres. Obama – for Indian prime ministers during this decade. This time she dressed in a Banarasi brocade sari, which turned out to match Michelle Obama’s outfit. Desai reflected on the differences between the coveted dinners in terms of invitees, décor and food: “Everything was beautifully organized in Obama’s state banquet. There were touches of novel Indians and Indian Americans and this was reflected in the unusual invite extended to young community players. The entire décor and food was meticulous and appropriate. The Obama dinner expanded the notion of what it means to be American by including Indian Americans.”

The Clinton dinner in 2000 for former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, she says, was about numbers – a record 700 guests, the largest ever for a White House state dinner. The dinner had an exceptionally large Indian presence, prompting Clinton to chortle in his toast to Prime Minister Vajpayee: “There are more than one million Indians here in America now. And I think more than half of them are here tonight. And I might say, Prime Minister, the other half are disappointed that they’re not here.” But even so, according to Desai, the food and décor at the occasion was not as memorable. Bush’s dinner was relatively small, with fewer than 130 guests, comprising principally of major Republican fundraisers and political heavyweights. So what’s Desai’s secret to being invited thrice? “It’s not about the individual,” she says. “It’s about the institution. Asia Society has developed strong relationships with leaders in India as well as Democrats and Republican leaders in the U.S.” Narender Reddy, president of a real estate company and a pioneer fundraiser for the Republican Party in Georgia, was among those invited to Pres. Bush’s dinner. He didn’t attend Obama’s event, but pointed out several differences in the recent state dinners: “Pres. Clinton’s State dinner for Prime Minister Vajpayee was attended by more than 700 people and was held in a tent on the White House grounds, just like the recent dinner hosted by President Obama, which was attended by about 340 people. Whereas Pres. Bush’s state dinner was hosted in the East Room in a very formal setting with only about 135 invitees, including the president and the prime minister’s delegations. Even the entertainment, a jazz band from New Orleans, was held in a huge room adjacent to East Room. Since there were fewer invitees, as an invitee, I felt like I am special and belong to an exclusive club. I also had the opportunity to mingle with other dignitaries more closely.” The intimate ambience allowed Reddy to meet and chat with Reliance Chairman Mukesh Ambani, Pepsico CEO Indra Nooyi, Vice President Dick Cheney, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. He recalls: “Rice was very nice to chat with. She enquired about my children and what their plans are for a career. Since I had met the president on several occasions in the past, I had a face recognition bond with Pres. Bush who introduced me, as ‘my friend Narender from Georgia’ to Prime Minister Singh.

Prime Minister Singh was very formal, but cordial. I thanked him for implementing the economic reforms in India. I spoke to him for a long time about the problem of excess fluoride in the drinking water of my native place Nalgonda in Andhra Pradesh and urged him to help. He was gracious enough to say that he would do something to help the people of Nalgonda. He asked me how long I’ve been living in America and when I replied that I’ve been here for the past 24 years, he appreciated that I was still think about helping my native place.” Such face recognition or verbal exchanges were out of the question for the large crowd of invitees at Obama’s dinner. Most guests had little opportunity other than to exchange pleasantries with Pres. Obama or Prime Minister Singh. However, NYTWA’s Desai recalls being prompted by an attorney friend of Obama’s to approach the president, saying he was open to such talk. So Desai with her guest trotted up to Pres. Obama during dinner to invite him to a taxi tour of New York City, “We were the only non White House people to walk up to Obama.” Obama responded that he would take up their offer once he was out of office, as the secret service would not permit such a visit while he was president. “It was amazing,” says Desai. “Obama was friendly, as was everyone else. It seemed like the more power an official had, the more approachable they were.” As the high profile controversy surrounding the Virginia party crashers exposed, the dinner was not without its glitches. A common complaint was the long wait, as much as an hour for some guests, in the cold and rain outside the South East gate that many guests, including a smattering of who’s-who of American society, had to endure. Some excited attendees saw a silver lining in that too, noting that the egalitarian process was a valuable humbling experience for great writers, directors and congressmen, as well as their opportunity to hobnob with them. Another frequent complaint, one that likely contributed to the gate crashing incident, was just how disengaged the Office of Social Secretary and the Office of Public Engagement seemed from the most important social event of the new administration. The guests said the invitation process permitted them no human contact, even to seek information or clarification; indeed most didn’t even knew who or which office was responsible for organizing the White House event. By contrast, Reddy recalls receiving a call from the Bush White House several weeks ahead of the dinner, asking him to keep himself available for the state dinner, for which the invitation was being sent in the mail.

There was also confusion and bitterness over the ceremonial reception held in the morning of the state banquet. Several of the dinner guests had been invited to the arrival ceremony of Prime Minister Singh and his wife Kaur at the White House. Because of bad weather, however, the event was moved indoors from the South Lawn to the East Room, severely limiting capacity. Several invitees, including some who had flown in from places as distant as Chicago or California, were not informed of the last minute switch and were turned away at the White House gates. Guests, such as Seecharran, who was returning for the evening dinner, took it in stride, but many others, who weren’t guests at the banquet, were disgruntled and disappointed. Then, of course, there were the notorious Salahis, who crashed the event. How did the invitees feel about the gate crashers? Says Seecharran, “I did notice Michaele Salahi. I didn’t know who she was then, but it was difficult to miss a tall, blonde and loud woman in a red ghaghra showing her belly.” Warts and all, for the Indian American invitees, the state dinner was a memorable event – an”experience to never forget,” in the word’s of SAALT’s Iyer – distinctive especially for the recognition of so many second generation community activists. Says Manavi’s Kelkar: “I felt really honored since this was such an enormous mark of recognition on a national level for Manavi since only 4-5 non-profits were invited. Since our jobs are not like corporate jobs where we have paid vacations and bonuses, and we deal with such sad and lonely cases stories daily, this helps mobilize and encourage us.” (Additional reporting contributed by Achal Mehra)

|

You must be logged in to post a comment Login