Magazine

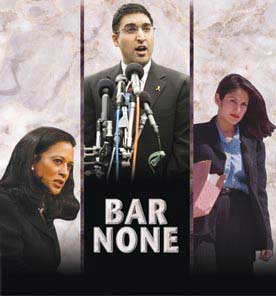

Bar None

A new breed of Indian attorneys is challenging the status quo.

|

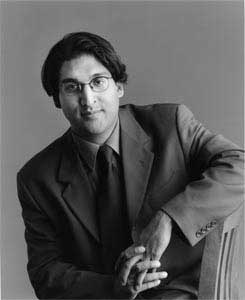

Who would think of challenging the post-9/11 might of Donald Rumsfeld and the Bush administration? A 34-year-old Indian American, Neal Katyal, that’s who.

Katyal is lead attorney in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, a federal challenge to the military tribunals set up by President Bush at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Katyal, a law professor at Georgetown University, is an expert in national security law, the American constitution, and the Geneva Conventions. His client, Salim Ahmed Hamdan, alleged to be Osama Bin Laden’s driver, has been languishing in prison for the past three years without a trial after being labeled an “enemy combatant” by the U.S. government. Hamdan is the public face of the hundreds of nameless, faceless detainees whose lives are on pause. “In these military tribunals at Guantanamo Bay, the President is acting more like a monarch than like a member of a democracy,” rails Katyal. “He has written all the laws, picked the prosecutors, picked the judges, and has even gone so far as to argue that the Supreme Court of the United States lacks the ability to review what happens at Guantanamo Bay.” Katyal argued the case in the Federal Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C., often described as the nation’s second highest court, in April, and it is widely expected that the case will ultimately end up in the U.S. Supreme Court. From what Amnesty International has dubbed the “gulag of our times” in Guantanamo, let’s move to the small town of Tulia, Texas, where in a early-morning raid in 1999 police rounded up 46 people, 39 of whom were African Americans, on charges of running a drug ring. They were all convicted solely on the testimony of Tom Coleman, a white undercover cop, and received prison sentences ranging from 20 to 99 years. Their lives were basically over until Vanita Gupta, a young lawyer, fresh out of law school, researched the two-year-old case, and smelt a rat.

Gupta, who had joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Legal Defense and Educational Fund as a Soros Justice Fellow, led the effort to overturn their convictions in 2003, and organized over a dozen national law firms for their defense. Eventually, all the defendants were pardoned by Texas Gov. Rick Perry. In 2004, she also helped them secure a $6 million settlement from neighboring Amarillo. The settlement also disbanded the narcotics task force that had been responsible for the drug sting. Now let’s move on to New York City, to the murky underworld of mobsters and mafia dons. Even the alleged heir of the Gambino crime family has the right to an attorney, right? Sarita Kedia, a Maharastrian from Mumbai, seemed an unlikely recruit to defend John A. Gotti “Junior”, but the unflappable, Kedia proved up to the task. As Gotti told the New York Times, “If I’m ever in a pinch, she’s the one I want next to me…she’s super-talented, she’s sincere and she’s an angel.” From the Godfather in New York, we turn to the frenetic crime scene in San Francisco, where Anjali Chaturvedi serves the new chief of the Organized Crime Strike Force in the United States Attorney’s Office (USAO) for the Northern District of California. She prosecutes organized crime cases that include human trafficking, criminal street gangs as well as narcotics, firearms trafficking and extortion. Her unit has indicted a number of alleged gang members and has gone after human trafficking, which has become a festering problem in the San Francisco Bay area. Earlier she had served as lead counsel to U.S. Sen. Diane Feinstein’s office on the Gang Prevention and Effective Deterrence Act.

In her 10-year stint at the Washington, D.C., U.S. attorney’s office, Chaturvedi tried several violent crimes, homicides and gang cases. She also successfully prosecuted the longest RICO (Racketeer Influenced Corrupt Organization) trial in the history of the U.S. District Court in Washington D.C., of the notorious K Street Crew, which involved over 100 witnesses and 18 associated murders. Katyal, Gupta, Kedia and Chaturvedi are among a growing breed of Indian Americans jumping into the legal ring, from judges, prosecutors and high priced corporate lawyers to idealistic public defenders. In the process, they are transforming Indians in the legal profession, which until now had been dominated by immigration lawyers, most in solo or small practices. For the past four decades, these immigration attorneys have served as the first line of protection for hundreds of thousands of clueless immigrants navigating the labyrinth intricacies of the immigration bureaucracy. Sometimes, these lawyers hailed from their hometowns, spoke their language and helped ease them, for a price, into America. But as the Indian American demographics change and the second generation comes of age, both the demands and the opportunities for legal professionals have evolved out of the narrow immigration groove. The North American South Asian Bar Association (NASABA), an umbrella organization of South Asian bar associations in the United States and Canada, attracted hundreds of these young high powered attorneys to its annual convention in June. The convention headlined Wally Oppal, the first Indian Canadian to be appointed a Supreme Court judge, who went on to become the district attorney of British Columbia. NASABA, which has 21 chapters throughout the United States and Canada, including nine added just during the past year, estimates there are about 5,000 lawyers of South Asian origin in America and Canada.

Increasingly, these young, second generation Indian American lawyers are the cream of the crop and are rapidly embracing all facets of the legal profession. These children of physicians, academics and engineers, are part of the big wave of young Indian Americans who headed to the nation’s most prestigious law schools, instead of medical or engineering studies at Boston, Harvard or the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a decade ago. Vijay Bondada, the outgoing president of NASABA and counsel in the New York office of Dickstein Shapiro Morin & Oshinsky, says, “My parents probably fit into that category, they wanted me to be a doctor.” Bondada, who graduated in law from Temple University in Philadelphia, Penn., observes “Law is perceived in India in a very different light than in the U.S. There is this perception that it’s a second tier profession, after medicine and after engineering. Obviously that affected their perspective on lawyers and also the fact that they are first generation and immigrants.” Indian immigrant children today, however, are as likely to turn to business and law schools as medical school. Says Bondada, whose father is an engineer: “I think a part of that is heavily driven by the fact that our parents’ generation, when they came over, were much more science oriented and English was a second language for them. Now that we are Americans first and English is the first language that we speak, law is a logical stepping stone for success in this country.” Says Bondad, “Many of us are in the nation’s courtrooms or sitting at the boardrooms, doing mergers and acquisitions and corporate transactions. So that is quickly coming to be.” He adds: “What really is the question is not just the numbers in the big firms – because we have the numbers – at NASABA about 60 to 70 percent of the lawyers there are at private firms, some of them at the nation’s leading firms. The question becomes how many of them are at the top of their game, on top of the food chain?” They are beginning to get there. Indians have broken into judge’s chambers, including Sanjay T. Kumar, who was appointed a judge of the Los Angeles County Superior Court. Kumar earlier served as a deputy attorney general for California and was involved in several high profile cases, including the murder convictions of Erik and Lyle Menendez and the Keating securities fraud.

Kamala D. Harris, daughter of an Indian mother and an African American father, was elected in 2003 as the first woman district attorney in San Francisco’s history as well as the first woman of color to hold that post in California. Other Indians involved in public service include Raj De, counsel, to the 9/11 Commission; Sri Srinivasan, assistant to the Solicitor General; Prakash Khatri, Immigration and Citizenship Services ombudsman, Department of Homeland Security; Shaarik Zafar, special counsel for Post-9/11 National Origin Discrimination, Department of Justice; and Neera Walsh, supervisor, First Municipal Community Prosecutions, Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office. Vikram David Amar, Akhil Amar’s brother, is professor of law at the Univer-sity of California, Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco, and has testified before congress on first amendment and constitutional issues. Professor Sonia Katyal (Neal Katyal’s sister) teaches in the areas of intellectual property, property and civil rights at Fordham Law School. Paul Grewal, a partner at Day Casebeer Madrid & Batchelder, in Cupertino, Calif., whose practice is concentrated in technology litigation, including antitrust, patents, copyrights, trademarks and the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, says, “It’s because so many of us came to law school with a technical or engineering background, there’s a significant percentage of our members in NASABA who practice patent law or intellectual property law.” Grewal’s parents hail from the Punjab; his mother is a physician and his father an engineer. Grewal says he has witnessed sweeping growth in interest in legal studies among second generation Indians. Whereas, earlier he would find just one Indian student in a law class, now it is not uncommon to find 10, 15, even 20 Indian students in a law class. “Parents have become much more supportive of their children going to law school. Bright young students coming out of colleges are looking at law as a way to climb the corporate ladder, or to try and make the world a better place, to do public interest work that really improves the community.” They are also taking risks and sometimes going out on a limb in challenging cases. Sarita Kedia, who came to be dubbed as the mafia lawyer, has built her practice on defending difficult cases. Growing up in the small town of Ruston in Oklahoma, she knew she wanted to be a lawyer and was already working at a law firm by the time she was 14.

She recalls, “Certainly, my parents encouraged me to become a doctor (as both my sisters are) rather than a lawyer, but I hated biology even in high school. I had also visited my older sister while she was in medical school when I was 12, and after seeing the cadavers I knew that wasn’t for me.” Kedia attended Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, where she secured her undergraduate degree in finance. After college, she interned at the Public Defender Service in Washington, D.C., which hooked her into law. “That was a fascinating experience, as I worked primarily with youths charged with extraordinarily serious offenses, some of them who I believed were wrongfully accused,” she recalls. “In particular, there was one 14-year-old boy from an indigent family who had shot and killed his best friend.” After investigating the case, she was convinced that it was an accidental shooting, but the District of Columbia charged him with murder. “It was then that I knew I wanted to practice criminal defense, both because I found it terribly thrilling and because I wanted to help protect people’s rights and assist those who have been wrongly charged with a crime.” Representing John A. Gotti (he is not actually a junior even though everyone calls him that, says Kedia) was one of the most rewarding experiences of her career. It was a big high profile case, which fascinated the press. Recalls Kedia, “From the moment that my then-boss Gerald Shargel took the case and asked me to work on it, I was unbelievably excited. The media couldn’t get enough of John Gotti stories; therefore, every time even the most trivial thing happened in the case, a story (or several) would appear in the newspapers or on television.” Since Shargel was involved in a death penalty trial, Kedia was asked to handle the Gotti case. She says, “At first, the client was extremely reluctant to deal with me, I think, because I was a woman and quite young – 28 – and not because I was Indian.” Gotti soon realized, however, that she was highly capable and grew comfortable with her. Adds Kedia, “What I believe sealed his faith in me was my writing the papers, which resulted in his release on bail, after nine months of grueling arguments against the government.” “But what makes this country so great – what secures our freedom here – is our constitution, and we need people, defense lawyers, to ensure that our constitutional rights are protected and not violated, especially by those in law enforcement or government.” Kedia, who was a partner in Gerald Shargel’s law practice, now heads her own small criminal defense firm, which represents several clients charged with securities fraud, mail and wire fraud, money laundering, bank fraud, bribery, racketeering, narcotics violations, murder, etc. Most recently she obtained an acquittal for a police officer charged in a steroid conspiracy. She also secured an acquittal for a grade school gym teacher, who has been charged with molesting nine young girls. She says, “I believe that this man, for example, was absolutely wrongfully charged, and if he had been convicted he would have spent the better part of his life in jail. Unfortunately, the damage to his reputation can’t be undone even with an acquittal, but he is able to have a decent life and move past the unfounded accusations.” Does she have a “dream” client? She laughs, “I don’t think so or else I probably would have tried to have a hand in representing him/her, but I wouldn’t mind a Martha Stewart or a Kobe Bryant type. I know it would be great for my career!” What might not appear quite as smart a career move would be representing someone who might have been the remotest association with Bin Laden, as was the case with Hamdan, whom Neal Katyal finds himself defending. “When I was National Security Adviser at the Justice Department, I was known for having a very hard line on terrorism and war criminals, and my academic writing is all about the need to be far tougher on crime than Americans have been,” says Katyal. “That said, I think there is a right and a wrong way to go about prosecuting terrorism cases, and we have definitely gone the wrong way at Guantanamo.” He says he has received letters from American servicemen and women around the world who have told him that in fighting for enforcement of the Geneva Conventions, he is protecting them and their rights.

Katyal, whose parents hail from the Punjab, recalls that they, like many Indians, did not think too highly of the legal profession: “In part, I became a lawyer because I saw what happened to my father, for when I was 15, he really needed a lawyer and couldn’t find an honest one who would help him. I went into law to try to change that.” Katyal has forged a worldwide coalition to challenge the Guantanamo Bay policies, which comprises of 305 members of the European and British Parliaments as well as several former senior U.S. military officials, including generals and admirals, all of whom have stepped forward to publicly endorse his work. Katyal, who attended Dartmouth College and Yale Law School, has had a hand in several groundbreaking cases. He served as National Security Adviser in the U.S. Justice Department and was commissioned by President Clinton to write a report on the need for more legal pro bono work. He was Vice President Al Gore’s co-counsel in the Supreme Court election dispute of 2000 and also represented the deans of major private law schools in the University of Michigan affirmative-action case, which the Supreme Court decided last year. The recent NASABA convention might have been a testament to the success of affirmative action, as nearly 60 percent of the 400 attendees were women. Says Paul Grewal, “I think two things have happened: families and parents have recognized that both potentially and financially law is a lucrative field, but also a field that carries a lot of prestige in the U.S., in American culture and society.” And Indian women certainly have no dearth of role models, starting with Preeta Bansal, who served as Solicitor General of the State of New York. A graduate of Harvard-Radcliffe College and Harvard Law School (where she was supervising editor of the Harvard Law Review), she was a law clerk to Justice John Paul Stevens of the U.S. Supreme Court, and later to Chief Judge James L. Oakes of the U.S. Court of Appeals. She currently serves as a commissioner to the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF), an independent and bipartisan federal agency. Vanita Gupta, too, has excited young law students everywhere with her heroic efforts at Tulia. She received several awards, including the 2004 Reebok Human Rights Award and the American Red Cross “Rising Star” Award. A Hollywood movie about her role in Tulia is now in the works, rumored to be starring Halle Berry as Vanita Gupta. Gupta is currently assistant counsel at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, where her work centers on civil rights litigation. Sabita Singh, the newly elected president of NASABA, says that South Asian women are entering the legal professional in large numbers. Many, she says, are activists, motivated by social justice issues, regardless of the legal specialty they have chosen. A graduate of Boston University School of Law, Singh is at Bingham McCutchen LLP, an 850-attorney international law firm, where she concentrates on white-collar criminal defense and business regulation. Earlier she was a prosecutor in the Middlesex County District Attorney’s Office, the largest office in Massachusetts, where she undertook both trials and appeals, including several high profile cases. She says, “It was one of those jobs where you can’t believe they pay you to do it; it was that satisfying. To come to the U.S. as an immigrant and then be able to work in our justice system, representing the government, well, it’s just an incredible immigrant experience.” During the time that she was a prosecutor, several of her cases were covered on Court TV, including the infamous Louise Woodward-Matthew Eappen case (British au pair/shaken baby case), which got international play. She remembers the outpouring of support from the South Asian community in the wake of the trial, with many people writing to tell her she had raised the profile of the community. She says: “I was so touched that these people claimed me for their own, yet I was personally so disconnected from the community. I was just doing my job, and had frankly given little thought to the needs of my community. “My eyes certainly opened up when I was contacted by South Asians telling me about their experiences with the justice system, some very, very sad stories. I was so disappointed, because I love this system in which I work. I wanted to make sure it did work for everyone. The need for South Asian attorneys to be involved, especially with the South Asian community, became clear to me then.” As president of NASABA, she believes South Asian lawyers can make a difference: NASABA’s criminal justice committee interacts with the Department of Justice to address concerns stemming from immigration policy in the wake of 9/11; an immigration committee monitors immigration legislation that may affect the community, and strategies for mentoring future lawyers are in the works. Anjali Chaturvedi, who heads the Crime Task Force in Northern California, supervises a unit involved with violent crime. Her parents came to New York from Uttar Pradesh in India, and Chaturvedi studied at Cornell University and Georgetown. She is discovering that Indians are now beginning to venture into criminal law. She says, “When I was in school, I didn’t know any South Asians – men or women – who did criminal law. So it’s encouraging for me to see that there are more of us now as we broaden our perspective and broaden our options. I think we can provide a unique role, particularly in criminal law, where unfortunately race can be a big part of a case. As South Asians, we are not aligned with any one polar side, black or white. I think that helps brings people together a little bit more, perhaps.” She believes South Asians will also be heartened to see someone like her in such a visible position: “I think South Asians have experienced a lot of difficulties after 9/11 and they may have a little bit more trust if they see someone like me making decisions in a criminal case. I like to think that people will have a little bit more trust if they’ve been prejudiced against before.” Subodh Chandra, who is currently running for attorney general of Ohio, was director of law in Cleveland, where he led a department of 82 lawyers with both criminal and civil divisions.

Chandra, who is a graduate of Yale Law School and was executive editor of the Yale Law & Policy Review, grew up in Norman, Okla. He recalls, “As I matured, I came to realize that many of the opportunities available to me in America as the son of immigrants were only because of the civil-rights struggles that African Americans endured. Civil-rights law matters, and taking a course in the subject as an undergraduate at Stanford further sparked my interest in becoming a lawyer.” Chandra, who in running for attorney general, will in effect be the lead prosecutor in Ohio, says, “But the most satisfying moments as a prosecutor were where because you did a little extra investigation, you decided not to prosecute someone because you decided they were innocent. Those moments don’t make headlines, but you remember that you can make a difference.” The Hamdan case, for Katyal, is about upholding powerful principles. He says, “It’s taken between 70-80 hours of pro bono work each week for more than a year. I have no time for anything else!” He shares an interesting memory of his first encounter with Hamdan. “When I met Mr. Hamdan for the first time, he kicked everyone else out of the cell where we were meeting. He asked me, ‘Why are you doing this?’ The question took me by surprise, since I had come prepared to talk about the legal implications of his case and what to expect, and not to talk about myself.” “I took a deep breath, and told him this: ‘My parents came here from India, the year before I was born, to give me a better life. They knew that America was a country where it doesn’t matter who your parents are, that you could succeed and be treated fairly. I have always been a patriot and loyal to my country, but what has happened at Guantanamo is not faithful to what our country is about. For the first time, the President has said that only foreigners are forced into these military tribunals at Guantanamo Bay. If you are an American citizen, you never face these tribunals, by explicit Presidential order. “‘That is a fundamental violation of our Constitution’s commitment to equality – for it says that if you are a green card holder or a foreigner, you get sent to this inferior fake court, where you could be put to death or face life imprisonment. Never before has the American government so radically discriminated between foreigners and citizens.'” This impassioned and lengthy explanation satisfied Hamdan and probably gave him some hope that in spite of being vilified as Bin Laden’s associate, he had a fighting chance in America. Katyal views his representation of Hamdan as a patriotic duty. “I do not think any other country would let a couple land on its shores, give birth, treat them well, and let their son clerk for a Supreme Court justice and have the job I had at the Justice Department. I’m very proud of our country and its rich traditions, and I see this lawsuit as upholding precisely that.” Determined vows for the new legal eagles preparing to take wing and soar. |

You must be logged in to post a comment Login