Arts

Another Peek

Mira Nair takes a fresh look at Thackeray's Vanity Fair.

|

In life, nothing is ever lost. Not even the books you read in your languid childhood. Director Mira Nair pored over William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair when she was a schoolgirl and now decades later, she has reinterpreted that classic piece of literature in a lush cinematic saga from Hollywood.

“This story has been one of my absolute favorite novels,” she says. “You know many of us have colonial hangovers in India and we are steeped in English literature. I went to an Irish Catholic boarding school in Simla and studied deeply Shakespeare and Keats and Vanity Fair was what I read, kind of slightly under the covers, when I was 16.” The studios offered her the film because of the whopping success she had with Monsoon Wedding and it was an added bonus that she knew and loved the novel. It is an irony that Thackeray would have appreciated, that this saga of Imperial England should be reinterpreted for the silver screen by a sassy and outspoken child of the former colony. And he would have been pleased, because Nair brings a whole new perspective to this tale of the Raj. An independent filmmaker, Nair usually produces her own work, only going the studio route when she is offered something with such a vast canvas that she would not be able to produce it on her own. This $23 million movie stars Hollywood superstar Reese Witherspoon as the beautiful and calculating Becky Sharp who rises from rags to the pinnacle of high society. The film also stars an ensemble cast of strong British talent including Eileen Atkins, Jim Broadbent, Gabriel Byrne, Romola Garai, Bob Hoskins, Rhys Ifans, Geraldine McEwan, James Purefoy and Jonathan Rhys Meyers.; “The big thing for me with Vanity Fair was that I am a helpless fan of Thackeray really and what I love about him is that he is almost an outsider in his own society,” she says. After all, Thackeray was born in Calcutta and raised in British India and when he returned to England, he could see it with a sharper focus, warts and all..

“And he wrote about a time that was acutely about the relationship between the Empire and the Colonies, a time I’m very interested in where England was first feeling the flush of wealth from what I call the rape of the colonies and was getting richer at home as a result.” I love that he asked what I call the yogic question – ‘Which of us is happy in the world and when we meet our desire, are we content?’ That is the essence of Vanity Fair.” For Nair the first challenge was bringing the printed page – 900 of them – to the movie screen: what do you leave out and what do you keep? So it was an intense collaboration with writer Julian Fellowes, who bagged an Oscar for his work in another period film, Gosford Park. The two hit it off instantly. She jokingly calls Fellowes the champion of cutlery and butlery from Gosford Park and was a little anxious when he was coming over to her home for dinner, preparing Western food too, in case he didn’t eat Indian. “In my house we eat with our hands, so I thought no cutlery to offer this chap! He instantly chose Indian food and he began to eat with his hands; we were friends for life!” Both of them had made their own maps of the book and then compared notes. Nair says, “What I wanted was this democratic swirl – this whole world – and this inter-relatedness of the characters, because Thackeray does this brilliantly. As Julian wrote the screenplay we used to exchange emails.” In fact, these emailed messages are now part of a book on the making of Vanity Fair, showing how the screenplay took shape. Says Nair: “For me, the task was how to amplify the frame, when we had a scene – how to jam in four or five other things from the book which otherwise I wouldn’t get to do entire scenes of, but to keep the details within each scene.” She was not interested in making it an anemic parlor room drama and wanted to evoke the outside world, the class culture of that time: “The shit on the roads, the pigs on the street, the coal mongers, the entire army of working class England who had to support the upper class to make them look and behave the way they did.

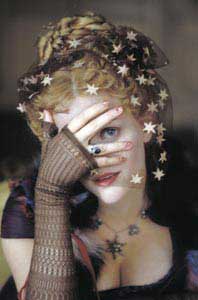

“And I wanted to do that in such a visceral way that without giving you a lecture, you would understand, as the audience, that if Becky made a false move – snakes and ladders – she would go right back to where she came from.” The film is very much about two different worlds and also encompasses the opulent world of the upper class with its balls and finery. Nair brings her energetic and very visual filmmaking to Vanity Fair, bringing it alive and giving it glamour with the many Indian and Oriental touches. Ask Fellowes about the collaboration with Mira and how they decided how much of India to put into the novel and he points out that there is a lot of Indian influence in the book, which is usually left out in other adaptations: “India has become this sort of other way of doing things, this freer other society where conceivably Becky may be more at home and that seems to me to be legitimate. We didn’t introduce the Indian theme into the stor,y but we did sort of reap it, rather.” So while the costumes designed by Beatrix Aruna Pasztor are of the period, they are dipped in Indian colors with exquisite detailing, and have almost a theatrical touch. Nair explains: “Thackeray wrote a very detailed, almost cinema verite, of his days. He always hreferred to the pashmina shawls, the inlaid marble tables, to the chinoiserie furniture, to so many illusions of the Orient, the colonies across the ocean, and how people coveted this in England. Again the colonies are such an important part of Thackeray’s fabric, no pun intended, that we went with that – the indigos, the crimsons, the teals, and the peacocks.” The wonderful influence of early Indian cinema and the sassiness of Bollywood are always present in Nair’s work and Vanity Fair has three dramatic song numbers and a wonderful sexy harem dance where Becky performs before the King. In the book it was a game of charades in which Becky played a slave girl, but Nair felt that this in-your-face dance number, choreographed by Bollywood’s Farah Khan, would convey the same shock value more powerfully. Laughs Nair, “It’s much more cinematic and we have this lovely Indian expression on the street, Paisa Vasool, which means, ‘I’ve got to give you your money’s worth.’ Give you a treat or sorry, we haven’t delivered. And I always like to give you paisa vasool.” In the ultimate paisa vasool, Nair also gives cinemagoers a rich eyeful, taking Becky to India, to all the color and pageantry of Royal Rajasthan. While this is not in the book, it seems just what the exuberant and adventure-hungry Becky Sharp would want, and enhances the cinematic experience. What’s next for Nair? As usual, she has several projects cooking, one being preparing Monsoon Wedding in a big, flashy musical for Broadway. Sabrina Dhawan is already writing the script and it will probably be ready around Fall 2005. She’s also directing a film version of Tony Kushner’s Homebody/Kabul for HBO, with Sooni Tareporewala writing the screenplay. Another big venture from Nair will be the film version of Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake: “I’ve fallen in love with that so I’m going to do that very quickly, right away, before doing Homebody.”

Always encouraging of new filmmakers, she has established an annual filmmaker’s laboratory, Maisha, in East Africa and India. The first lab, with an emphasis on screenwriting, is planned for August 2005 in Kampala, Uganda. She’s also launched International Bhenji Brigade (IBB), a partnership with Bala Entertainment International and Venkateshwara Hatcheries to bring the work of young filmmakers to the screen. Always outspoken, she says she made Monsoon Wedding on so little money “purposely to prove that you don’t need a whole lot of money and men in suits to tell you how to make a good movie.” She recalls a time when she got a grant to make her very first documentary So Far From Home and the other grantees were overwhelmed with gratitude for being given the funds. She told them, “You know, we have such a voice to say, to speak in this world, you shouldn’t just be grateful. The other people should also be grateful to you for bringing your own voice to the world.” She adds, for the benefit of those embarking on the same journey: “So I must tell you that I don’t sit around looking over my shoulder, hoping that they won’t catch me or something. I think it’s the other way around. I think I have something to say and I have a point of view on the world that I have to offer, and I’d like to open your eyes to that part of the world that I come from. It’s not gratitude, it’s a two way process.” And in this give and take, in this two way process, Mira Nair has brought her own perspective to Vanity Fair, the ultimate tale of high and low society, adding in unique shadings and nuances, redolent of her own Indian background, to enhance the larger picture. After all, India was an invisible but powerful presence running through 19th century England – and Mira Nair has underscored that in her retelling. |