Arts

A Musical Life

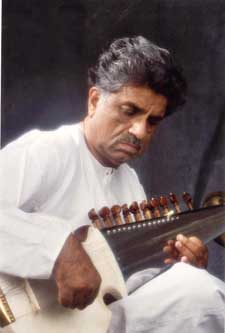

Rajeev Taranath on music and extraordinary musicians.

|

He recites T.S. Eliot with the same ease with which he plays the sarod. A linguist, who once fooled a diverse array of people from different Indian states by speaking their own dialect flawlessly, he is also a highly accomplished singer who was invited to become Bollywood’s golden voice. But then Ustad Ali Akbar Khan happened to him, and Rajeev Taranath was hopelessly hooked to the sarod.

In an exclusive interview with Kavita Chhibber the sarod maestro, who is also a PhD in English literature, talks about his extraordinary beginnings, his relationship with Annapurna Devi, the elusive ex wife of Pandit Ravi Shankar, Shankar himself and the man whose music makes him fall in love with melody over and over again – Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, Annapurna Devi’s brother. Your mother and father seemed to be way ahead of their times. What truly extraordinary beginnings for a child born in the 1930s. My father was tall and handsome like a Roman soldier and a true Renaissance man. He was like Da Vinci – a physician, a table player, a singer and a freedom fighter. He was an allopath who was also an expert in Ayurveda and Yunani medicine and he successfully treated lepers, helped unwed mothers. My father taught me tabla in order to teach me Ayurveda. There is an interesting connection. Just like in tabla where your fingers have to get the subtlest sense of rhythm, in Ayurveda you diagnose disease by checking the patient’s pulse. Each subtle variation signifies a certain ailment. Music he discovered had a strong healing effect. He would sing a particular raga which strangely would cause fever to come down. I grew up listening to musical geniuses like Abdul Karim Khan sahib. Before I knew how to read, I could put any record on the gramophone and know what was in it. I had memorized every little detail on every record in that collection. I learnt Ayurveda under his supervision. He knew the day he was going to die. Two days earlier he had told my mother that he was going to die and how to treat each patient. He also told her that she would be the mother for everyone from now on, and must not dress in a widow’s garb. That day in 1942, he asked me to sing a song he had composed -“Darshan bin mohe chain nahin,” and then went in to lie down. He called my mother as I continued my tabla practice at his behest and the next time I saw him he was unconscious. I was 10 when he passed away. He did not want me to come to the crematorium and to remember him as a vibrant, healthy father. His friends cremated him. My mother was a very special lady. She was a dusky beauty who wrote what was probably the first book on sex education for girls in English in India in the 1920s. In fact she was selling these books on a railway platform wearing a Nehru cap when Pandit Nehru saw her at the station and asked to see the book. Their discussion was so animated that the train started and Nehru had to pull the chain and helped my mother get down. He became very fond of her. She too passed away when I was 20. I had a good voice and was considered a child prodigy and was surrounded by admirers, all of my father’s age, until I turned 15 and my voice cracked. The cuckoo became a crow and everyone disappeared. I did sing again later in college for the fun of it and won many prizes. Talat Mehmood heard me sing and asked me to come to Bombay and meet with him. He said he will try and help me break into play back singing. And then?

And then Ali Akbar Khan happened to me and the rest is history! In 1952, Panditji came to Bangalore for the first time with Ali Akbar Khan. Until then I had a pronounced dislike for sarod. I had heard the instrument on those hard older 78 rpm records and it came across as a staccato and harsh instrument. I took a girl with me who loved my filmi singing, escorted by her father, to see Raviji in concert. When I entered the hall, there he was, the handsome young Ravi Shankar who looked like the live incarnation of Lord Krishna – all he was missing was a peacock feather around his head and a flute. And then followed Ali Akbar Khan trudging stolidly behind, wrapped around his sarod like a tired wet towel, a balding Buddha and he hasn’t changed much. When the performance ended, the girl, her father all seemed like a distant dream. Until then I had been this brilliant English scholar, a super debater, a good singer of Talat Mehmood songs and a pretty good cricketer, preparing to sit for the civil services exams, and now it was as if everything was wiped out from my life – all that remained was Ali Akbar Khan’s music. It took me a year and a half to even get an introduction to Khan sahib. When I told him I wanted to learn the sarod from him, he said, “You are mad. I heard you are a professor. You have a great career ahead of you.” I didn’t budge. Finally he gave me my first lesson and still told me to go back to Bangalore and think about the things I may have to give up in order to chase this musical dream of mine. I obediently went back to Bangalore and returned again to knock on his door. He looked at me and asked, “Why are you here? What happened?” I said that I had resigned my job. He looked at me and said, “You are mad!” but took me in. You met Annapurna Devi there. She remains an enigma to this day and many people say many things about her. While she and Raviji are not on talking terms, and Ali Akbar Khan too has fallen out with Panditji, you have had an ongoing cordial relationship with all three. What are your thoughts on them? She is a wizard on sitar and surbahar, and I would often go to where she was after finishing my lesson with her brother and listen from a distance. She is a hard taskmaster. If you messed up, you would be made to repeat the same exercise 100 times. I was the proverbial poor church mouse when I went there and caught the famous Calcutta ailment, amoebic dysentery, but had no money to go to a doctor. I lost over 40 pounds, wasting away. I was asked to sell my sarod by this musician who knew of my pitiful state. He said he will pay me handsomely. I could then finally indulge in one good meal, get all the medical treatment and then go back to Bangalore. I almost sold out, but went to sitar maestro Nikhil Bannerjee instead who was also there. He laughed outright – “You’ve left everything for sarod, struggled for two years and now you want to go back?” After many years, for the first time, I felt like I was not motherless any more. In a strange coincidence she resembles my mother tremendously. She lives an austere life and has set the bar very high. Pandit Ravi Shankar is an amazing man. He is so bright intellectually that if he hadn’t been a musician may be he would have been a space scientist. He learnt from a guru who was very demanding, very intense but Raviji was able to learn everything very quickly. Raviji has always been a pioneer, a man who has been way ahead of his times in anything he does. He is also instrumental in forcing me out of a hiatus I took from music. There came a time in my life, due to personal reasons, I gave up on active performance, in spite of having gone through so much to become a sarod player. I went back to being a professor of literature when Raviji came to perform in my city. He took me to task for giving up on music and asked me if I felt I owed anything to the gharana and the gurus who had given me such a treasure of music. He told me to stop thinking and go back to music. At 51 years of age I went back, because he knew how to get me to focus in his usual no nonsense crisp way and I’m glad I did. Ali Akbar Khan, what can I say about him. He is composing all the time. Between the given and the improvised, what is given is so ventilated that sometimes it can be blown away if you are not careful. There are two kinds of musicians, one who makes sure he sticks to the known path, so no one can fault him, and then there is the other who pushes the boundaries. Khan sahib is among the latter. Whether it’s music or art, there comes a man who pushes at the possibilities in a way that when he is done, we never look at music, or art or literature the same way. Khan sahib’s relation with music is that way. He is not a dazzler, he may not have the greatest pyrotechniques and yet what he is doing is having a constant affair with melody and experimenting with all kinds of tonal possibilities. It is only after he started performing that the sarod began to be recognized as an Indian classical instrument which had great tonal possibilities. No one, not even his father who was a musical genius and played so many instruments brilliantly could garner that respect for sarod.

Your research as a Ford Foundation scholar was on the teaching techniques of the Maihar-Allauddin Gharana. What did you come away with? Look at all the great musicians and look at the number of maestros Baba Allauddin Khan produced – Ravi Shankar, Nihkil Bannerjee, Ali Akbar Khan, Annapurna Devi are just a few names. Allauddin Khan was the fountain from where all the streams of talent emerged, each with their own unique touch, but it’s the water from that fountain that keeps hrefilling and hrefurbishing those streams. No matter what instrument we play and Baba taught every instrument on the planet, you will see familiar flashes in each of our play, and that is the beauty of the Maihar gharana. Another thing, he created great musicians in every genre. In other gharanas you will often see the teacher producing students in his own mould, but the versatility that comes from the Maihar gharana is mind boggling.

Peope talk about fusion and that good music is struggling today. What is your take on that? For me music is like meditation and it should be like meditation, but musicians are the products of their time and audience. Vilayat Khan’s and Ravi Shankar’s era could not have produced an A.R. Rehman, and A.R. Rehman has his own brilliance. Also on the flip side, the audience is also drawn to a musician that the culture of that time produces, but eventually in the totality of it all, the boundaries of music are limited or expanded by the ears of the audience. What kind of audience do you like playing before? |

You must be logged in to post a comment Login