Life

Why So Many Indians Support Gurus Like Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh

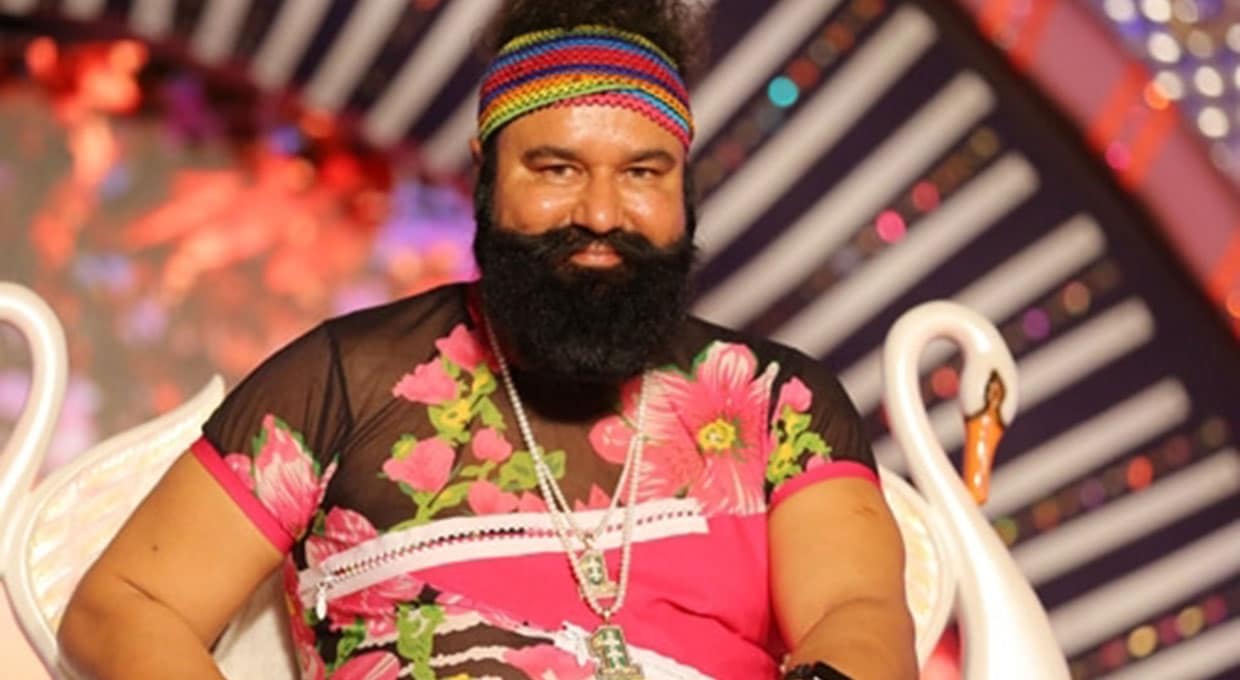

Dera Chief Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh

IANS

In this rapidly industrializing country, "alternative spirituality" persists despite increasing levels of education and increased economic prosperity.

The guru sits in jail now and his town is already showing the bleak signs of departing abundance. New factories have their shutters rolled down, men are complaining of unemployment, military guns are everywhere.

Sirsa, a town in northern India, headquarters of the Dera Sacha Sauda sect, is reeling without its spiritual leader, Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh, who was sentenced Monday to 20 years’ imprisonment for raping two women followers.

The conviction came after a decade-long legal battle, during which victims revealed details of being invited into Singh’s underground residence where he watched pornographic films and forced himself upon them.

Minutes after the judge pronounced Singh guilty, violence erupted in Sirsa and outside Panchkula court, where Singh’s devotees thronged the streets. A total of 38 people lost their lives, as rioters threw stones and torched vehicles.

Ravinder Saini watched from his roof as a government-run milk factory burned. “For two days the factory was burning. No one came,” Ravinder said.

Now, the riots have ended, but the townsfolk are left with fears for their future.

Singh claimed to have over 60 million followers. Garbed in sequined costumes and gold jewelery which earned him the nickname “guru of bling,” he produced outlandish music videos Over the years, Singh’s popularity made Sirsa prosperous.

“From a purely business perspective, his organization was good for me,” said Pradeep Saini, a 25-year-old shopkeeper.

Singh’s is hardly the only outsider sect to have found a foothold in India. In this rapidly industrializing country, “alternative spirituality” persists despite increasing levels of education and increased economic prosperity, said Ronki Ram, a professor of political science at Panjab University. Sermons from religious teachers are beamed into homes on religious channels, and a number of self-styled “godmen” have amassed fortunes selling branded products.

People buy into religious rhetoric, Ram said, because godmen are often charismatic speakers and make their followers feel part of a fraternity.

“People from all walks of life go and attend,” he said. Establishment religions such as Hinduism, he said, trap lower castes at the bottom of the social pyramid, offering no way to rise up. To them, being part of the “alternative” religious clubs offers “equality, dignity and social justice,” he said. “A poor man goes and finds himself in a room with a minister, and suddenly he feels, ‘Oh god, I’m not alone!’ ”

Inside the compound now sealed off to the public, Singh lived a life of luxury, surrounded by doting followers who attended to his every need. Luxury cars and lavish furniture surrounded him. The complex includes a hotel, an auditorium for sermons and a large meditation hall. His larger-than-life personality attracted rich businessmen and politicians who came to seek blessings ahead of a new venture or an election.

To cater to the pious, grocery shelves in the city are stacked high with the guru’s own brand products. Movie theaters show films starring Singh, sometimes as a motorcycle-riding superhero. Shops are plastered with photos of the rhinestone-garbed “rockstar baba.”

“It has been profitable here,” said Prabhu Ram, who sat under a tree playing cards with his friends. “There has been employment for the men in the factories, schools for our children. Even the value of land has appreciated.”

“We think of this place as heaven,” said his friend Parhlad Singh, who works in one of the factories run by the sect, cleaning and packing pulses, the grain legumes common in Indian cooking. “The work is good, their product is good and I am able to run my house on what I earn.”

But now all that seem in jeopardy.

“Everyone fell silent, and it felt like we had gone numb,” a resident named Satbir Singh said of the moment when the verdict was announced – on television. “Our father has gone to jail, but we hope someone keeps the organization running.”

In a village less than a mile away from the Dera sect’s headquarters, a group of farmers sat in a muddy field smoking a hookah pipe. “He provided so much employment. So much development,” said Mahaveer, who uses only his first name. “We all think that the accusation was false.”

Shaking his head, Mahaveer said, “The Sirsa district will fall back now. I feel they should release him. Earlier this was such a desolate area. Now look at the difference. We have public transport here, two fire engines and a hospital. We have nothing else that we need or want right now. The Dera has given us every facility. We have schools to educate our children. Colleges for them to study as much as they want.”

A number of godmen like Singh have held on to vast numbers of followers despite allegations of criminality. Baba Ramdev, a stomach-flexing yogi who led an anti-corruption campaign, was investigated for tax evasion. Asaram Bapu has been jailed on charges of rape and criminal intimidation. But supporters are willing to overlook crimes, Ram says, because they see their own lives tangibly improving after joining sects.

“It is a social protest for a new identity,” Ram said, noting that holy men are often praised for their vast and wide-reaching social programs. Singh particularly was known for his huge blood-donation drives, anti-drug messages and performing mass marriages of sex workers.

“I have been a follower since the beginning,” said Prabhu Ram. The sentence was wrong, and harsh, he said. “They have given hospitals; there are eye camps,” Ram said. The state government, he added, “would not have made all this progress.”

A young woman of 18 named Pinky refuses to doubt Singh’s moral character. “He did so much good. He never did anything bad,” she said as she washed cooking utensils in a drain running alongside the road. “I believe the rape charges are false,” she whispered.

— Washington Post

You must be logged in to post a comment Login