Once again, Bollywood, the world’s largest film industry, has taken a beating at the world’s oldest and most celebrated film festival.

Founded in 1939, the Cannes Film Festival is an annual film spectacle held in May at the Palais de Festivals et des Congres, in the small resort town of Cannes, in south France. Over the years, it has developed a reputation as the world’s preeminent film festival and has come to be revered by both the magicians and the merchants of cinema for its moolah and mystique. A platform where the movie community congregate to celebrate the finest work available amidst a glorious backdrop of sea, sand, sun and endless carnivals.

This year’s countdown includes headliner like Lee Daniels’ The Paperboy, Michael Haneke’s Amour, Water Salles’ On the Road, David Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis and of course Andrew Dominik’s, Brad Pitt starrer Killing Them Softly. The high point could be the aged mastero Alain Renais’ latest movie, Vous N’avez Encore Rien Vu (You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet).

The country that produces the largest number of films on earth (1,000 annually), will be conspicuous by its absence, however. Indian films and filmmakers, glorified and glamorized at home, don’t register even as an exotic blip on Cannes radar. Can you remember the last time an Indian film was felicitated at Cannes? In 1999, Murali Nair’s Marana Simhasanam, a short film critiquing class and political manipulation set in Kerala was screened at the Un Certain Regard (A Certain Glance) section of the festival, which encourages innovative and daring works, and walked with the prestigious Camera d-or award, given for best first film.

This year Ashim Ahluwalia’s Miss Lovely was selected to represent India in the Un Certain Regard section. No film from India, however, was found worthy of the competitive section. Sure we are treated to the glitzy “side-shows,” such as Aishwarya Rai and Sonam Kapoor doing a red carpet ramp-walk as a L’oreal brand ambassadors and Arjun Rampal strutting his stuff for a liquor brand. Anurag Kashyap’s five-hour epic The Gangs of Wasseypur, was screened as part of Director’s Fortnight and Vasan Bala’s Peddlers, was showcased under Critic’s Week. Both the Director’s Fortnight and Critic’s Week are independent sections, held parallel with the Cannes Film Festival and run not by Cannes, but the French Director’s Guild and the French Union of Film Critics, distinctions that are glossed over by both the Bollywood publicity hype machines and the gushing Indian media.

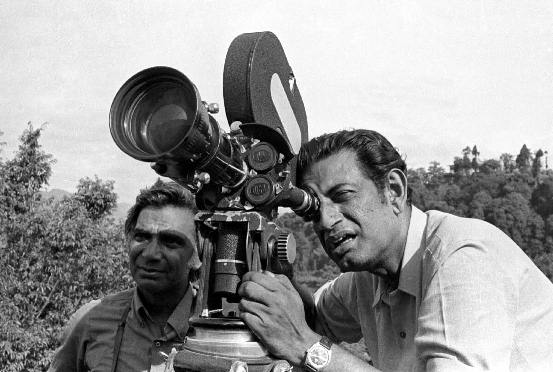

Don’t Indian films count for anything, anymore? Has the festival that once worshipped Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak and Adoor Gopalakrishnan, completely turned off by the stuff we produce? What’s the problem? What’s the solution?

Okay, so what does India’s large contingent do once it touches down at Cannes? Booze, laze around, ogle topless babes and generally have a blast? Veteran journalist and scholar Rauf Ahmed laughs, admitting that there are certainly delegates that fit that stereotype, but there are serious movie junkies too. “One is the kind who genuinely want to see films to check out the best of world cinema. Guys like Sudhir Mishra, Ketan Mehta and their ilk. They know why they are going there and what will come out of this amazing 10-day experience. There is focus, clarity and sense of purpose all the way. The other lot come to sell their films because Cannes is a huge market place too with a robust, vigorous, vibrant and hyper-active market section. There is something for everybody and with the diaspora (the pre-sold red-hot target base) on an over-drive, the potential possibility of making a quick buck is always there.” In recent years, according to Ahmed, the marketing of Bollywood at Cannes has taken a big leap.

The awkward fact remains that although Bollywood is the world’s largest movie factory, we don’t register even a hiccup in this gala, global, mega feast. Historically we have been conditioned and programmed to believe that it’s not the winning or losing, but participation that is the key. Ride the karma cloud, without anticipation of rewards. It gives our weak performance a philosophical coloring.

There is also the hard reality. We simply don’t or can’t, make films that resonate with the world. Our stuff is not universal, but local, celebrated hugely at home and among the diaspora across the globe. Cannes, on the other hand, looks for unique, unusual and edgy works that are global in character, an individual voice that is riveting enough to be heard and loved across the globe, culture-specific films with an all-embracing soul, in which Iranians and Chinese specialize. We seem to have forgotten to make such films.

Critics blame the Bollywoodification of India for its weak performance in international circuits. Says one critic: “Their gloss, glitz and glamor has such an over-powering influence on the Indian viewer, wherever on earth he may be, that it’s nearly impossible to let anything else get peeping space. In this scenario, when mass popularity and numbers decide everything, where does genuine pursuit of excellence stand a chance? Sadly, the Bollywood product is only popular with the Indian diaspora, but such are their growing numbers, that they are made to count. Cannes, while acknowledging the Bollywood phenomenon, has no time for its product because it does not conform to their idea of great cinema. It’s exotica, at best; endless, irrelevant, song n’ dance at worst! Isn’t it amazing that a few years ago at Cannes, they played Ray’s Pather Panchali — a film that is totally rural Bengal-specific and made over 50 years ago — to packed halls attracting rave reviews from viewers across generations ….”

However, all is not lost. The attention that Cannes is now attracting and the growing Indian participation is a learning experience for Indian filmmakers and before long some will break though. Until then, Aishwarya Rai Bachhan haazir ho!

|

Indian Movie Winners at Cannes

1946: Neecha Nagar (1946, Chetan Anand). Grand Prix 1954: Do Bigha Zameen (1953, Bimal Roy). Grand Prix 1955: Boot Polish (1954, Prakash Arora). Special Distinction to child artist Kumary Naaz 1956: Pather Panchali (1955, Satyajit Ray). Palme d’Or 1957: Gotoma the Buddha (1956, Rajbans Khanna). Unanimete 1983: Kharij (1982, Mrinal Sen). Jury Prize 1988: Salaam Bombay! (1988, Mira Nair). Camera d’Or 1989: Piravi (1988, Shaji N. Karun). Un Certain Regard Prize 1991: Sam & Me (1991, Deepa Mehta). Camera d’Or Mention 1998: The Sheep Thief (1997, Asif Kapadia) – Cinefondation 1999: Marana Simhasanam (1999, Murali Nair) – Camera d’Or |

You must be logged in to post a comment Login