India

Dharamsala: Permanence Of Exile

| Fifty years after tens of thousands of refugees streamed out of Tibet following a failed uprising against Chinese occupation, their hopes of returning to their homeland are fast receding and the Himalayan town of Dharamsala — the de facto capital and home to nearly 20,000 Tibetans in exile — is taking on all the trappings of permanency.

Exiled Tibetans have become one of the world’s most visible refugee communities and their spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, a Nobel laureate, has become a global icon celebrated for his humanity and Gandhian, non-violent struggle for a Tibetan homeland. But as Tibetans worldwide on March 10 marked the 50th anniversary of the Dalai Lama’s 1959 flight from Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, there was no escaping the hopelessness of their quest to reclaim their homeland. Even the Dalai Lama has admitted: “I have spent most of my life in this hill station. Now I feel like a citizen of Himachal Pradesh.”

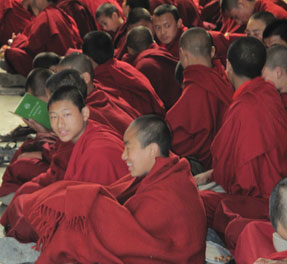

Beijing’s hard line against the exiles, as well as its brutal repression of the nearly 5 million Tibetans in China perceived as separatists or sympathizers of the Dalai Lama, makes it increasingly unlikely that any exile will ever return to Tibet. Instead, an estimated 2,000 Tibetans risk their lives crossing the treacherous Himalayan ranges to escape Chinese control every year. Indian Prime Minister Pandit Nehru offered the Dalai Lama and the nearly 8,000 Tibetans in his Central Tibetan Administration political asylum and a section of the British Raj hill station in Himachal Pradesh of Dharamsala (religious abode), which now serves as the seat of the exiled government. Over the years, Dharamsala has been transformed into Little Lhasa, as the original Shangri-La eludes their grasp. It is now an internationally renowned Tibetan community, pulsating with Tibetan architecture and cultural rhythms, where thousands of monks mingle comfortably with international tourists and long-term foreigners, many of whom have spent years in monasteries and voluntary organizations. Set in the verdant Kangra valley in the Dhauladhar mountains, nearly 20,000 Tibetans have settled in and around Dharamsala, including Mcleod Ganj, Sidhbari, Chauntra, Bir, and Tashi Jong, making it the largest settlement of overseas Tibetans. In all, an estimated 140,000 Tibetan refugees are scattered all over India and Nepal in 36 communities in small towns in Himachal Pradesh, Uttrakhand and Jammu and Kashmir, as well as Bylakuppe in Karnataka and Gangtok in Sikkim. Bylakuppe is the second largest Tibetan settlement after Dharamsala with 10,000 Tibetan residents, with numerous monasteries, nunneries and temples, including the famous Lugsum Samdupling and Dickyi Larsoe monasteries, which like the Norbulingka Institute and Gyuto Monastery in Dharamsala, seem like they were transported brick by brick from Tibet. Both Dharamsala and Bylakuppe were established on land leased to the Tibetan authority by the Indian government.

Another 80,000 Tibetans are settled in the West, including Canada and Switzerland. Massive Tibetan temples have sprouted in the remote regions of Northern California above San Francisco and in New York. Scores of small Tibetan communities thrive all over Europe and the United States. But the heart of exile Tibetan life beats in Dharamsala, home to the Dalai Lama, the Karamapa Lama, who is third in line, as well as other high-ranking Lamas and monks. Dharamsala has two distinct sections. Upper Dharamsala, or McLeod Ganj, popularly known as Little Lhasa, is where most Tibetans live in crowded streets and where the Dalai Lama has his residence, just opposite the Tsuglag Khang, the central cathedral. The largely Indian Lower Dharamsala, 8 kms down the main road (but which locals navigate using a 3 km steep hill road named Khara Danda), is remarkably different from Upper Dharamsala. Nearly 20,000 people, almost all Indians, live in and around lower Dharamsala, while Mcleod Ganj is home to some 12,000 Tibetans and permanent westerners residents. Mcleod Ganj’s tiny streets are packed with tourists, mostly westerners, but also domestic visitors on weekends. Lower Dharamsala, by contrast, is a typical Indian hill town, reflecting pahari (Himachali) culture and crowded bazaars, which Tibetans and Westerners frequent for grocery and household supplies. The semi-nomadic Gaddi, the locals, once the dominant ethnic group, have struggled to hold on to their culture and language. At first poverty-stricken and jobless, the Tibetans have slowly swamped the local population with their rich and colorful cultural traditions, religion and the Dalai Lama, attracting the attention of the world and thousands of enlightenment seekers who swarm the Tsuglag Khang — the main temple just opposite the Dalai Lama’s residence. Tibetan monasteries, schools, refugee camps and education centers in Mcleod Ganj have put their distinct architectural and cultural stamp on the town.

The Little Lhasa section of Dharamsala is a unique ecosystem of Tibetan schools, monasteries espresso cafes, guesthouses, Web-surfing monks and tourism related industries, serving as a global node for pilgrims, backpackers and Tibetan Buddhism seekers. Tibetan prayer flags flutter atop homes and in the hills, and maroon-robed chanting monks and other symbols of Tibetan life are visible everywhere. The town seems like a throwback of another Lhasa, where monks and nuns perform their daily religious duties and other Tibetans remain preoccupied with their daily lives, some working for the Central Tibetan Administration, while others work in Internet cafes and other tourism sectors. Tibetans in Dharamsala seem to sustain a tourist economy simply by being Tibetan for the benefit of nearly 350,000 foreign and an equal number of domestic tourists every year. Says Rachel Bubu, a journalism student from Quebec, Canada, who has been volunteering at the Tibetan Women Association (TWA) Center in Dharamsala for nearlytwo months: “This place is very different. Dalai Lama’s Dharma teachings in the snow-capped hills makes it so special. The mix of Indian and Tibetan culture makes it so special. Here it’s not like a vacation, but like a place where one loves to stay for long.” Ana, a tourist from Madrid, Spain, adds, “These mountains and Buddhist are very attractive and give me peace of mind.”

Chavi Chamish, a backpacker from Tel Aviv, Israel, who is staying in the Bhagsu section of Dharamsala, which is popular among Israeli backpackers and hippies, many of who are taking tabla, yoga and Hindi classes, says: “Dharamsala has so many colors. It’s a place for living and learning. There is no doubt Tibetans have made this tiny town a heaven with international presence and a home away from home.” There is surprisingly little animosity between Indians and Tibetans, notwithstanding their religious and cultural disparity, even among the Gaddi, the local tribe, who have lived here for generations and seen Tibetans move into a position of economic dominance. In part this is because they too are beneficiaries of the tourist economy, which is powered by the presence of the Dalai Lama and Tibetan culture. Ajay Sharma, a businessman who runs a money exchange shop in Mcleod Ganj, says, “Currently there is nothing much we both communities complain about and it should remain like now, where both earn mutually, sharing hands.”

Dharamsala recently opened a new international cricket stadium overlooking the snow-capped mountains, which residents hope will drive further economic growth in the region. Says Ramesh, an Indian taxi driver in the city, “Hum sab aage badh rahe hain, sabko saath chalna hoga ek ghar ki tarah hai tabhi sabh kush hai (We all are growing, all of us have to proceed together, like a family, then only will we all live happily).” Tibetans revere the Dalai Lama and most credit him for keeping their culture and identity alive. They support his initiatives for a dialogue with China and his advocacy of compassion and non-violence, which has made him an international diva. When at his exile residence in Dharamsala, he is preoccupied with public and private meetings and his tight schedule of pujas and other religious duties as a monk. The Dalai Lama dismisses his global celebrity: “I am just a simple Buddhist monk — no more, nor less.” But even after 50 years in exile, he remains a tireless advocate of a Tibetan homeland: “My body and flesh is all Tibetan. I remain committed to the Tibetan cause.” In recent years, the Dalai Lama has steered a “middle way” for an autonomous Tibet within China. “I constantly look back at the last 50 years. I always feel I made the right decision,” he said in his the 50th anniversary exile speech. He remains optimistic about returning to his homeland and takes comfort in the fact that the Tibetan cause remains alive and is even finding growing support among the international community. “Seen from this perspective, I have no doubt that the justice of Tibet’s cause will prevail, if we continue to tread the path of truth and non-violence.” Dolma, an elderly Tibetan exile who fled to Dharmasala in the 1960s with her family, embraces the Dalai Lama’s approach: “Tibetan people’s resistance is not against Chinese people, but to display their desire to protect the legitimate rights of the Tibetan people and their rich and valuable culture. Everyone knows His Holiness is the Gandhi of our time and we accept his approach of non-violence. We are refugees and one day or another we must go back.” Woman praying in the streets.

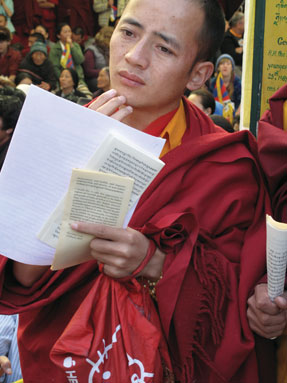

Her sentiments are shared by Tenzin Delek, an elderly monk: “We Tibetans have left our homeland in search of freedom and the desire to live our lives as we see fit. We did so to avoid political oppression and religious persecution. Living in exile has strengthened the resolve of Tibetans to regain their homeland.” Adds Gompu, a Tibetan born exile, “No matter where I live now, but if you ask me my true home it will always be Tibet. ” However, over the past decade fissures have developed in the community over the Dalai Lama’s approach toward China. Most elders agree with his “middle way” strategy, which seeks an autonomous region of Tibet inside China. But many youth are growing impatient with the lack of progress and are rallying instead for rangzen, or full independence, and have begun targeting the Bejing government with public protests in India as well as in the West, provoking complaints from Beijing. There is a general sense that many of the young radical Tibetans in exile, such as those represented by the Tibetan Youth Congress (TYC), are presently constrained because of their reverence for the Dalai Lama, but they may feel freer to pursue more drastic action once the Dalai Lama, who is aging, passes away. “This is the time for uprising, to raise the issue of Tibet at the international level,” says a young Buddhist monk. “The people of the world support us because we have true injustice. Yonten, a young Tibetan who fled to India in 2000, is equally impatient: “I now dream of my homeland every day. Fifty years are enough, its time for us to get back to our home.” TYC president Twesang Rigzin says:”No doubt, no one will be able to replace the Dalai Lama and we Tibetans won’t be able to repay him. But we are struggling for an independent nation and our struggle will continue.”

But the exiles have seen their free Tibet hopes flicker and die countless times. Protest flags against the Chinese and Free Tibet posters are everywhere in Dharamsala. Monks and nuns outnumber revelers, performing hunger strikes on every major event, hoping to bolster world opinion to their cause. Tsering, a young Tibetan, says: “I feel the same as other Tibetans born in Tibet. I am eager to see my homeland, meet my people and glimpse the stories told of our old people. As a Tibetan born in exile I have more responsibilities to make every effort possible to help my people back in their own homeland.” Meanwhile, Tibetan children learn both Hindi and Tibetan in school, the first to prepare them for a life in which they may never go to the homeland they have never seen and likely never will. While daily life embraces endless obeisance to Tibetan religion, with prayer wheels spinning endlessly, most Tibetans have begun assimilating with their Indian identity. Although presently there are few intermarriages between Tibetans and Indians, given the proximity of the two communities, these will no doubt grow. “I live more like an Indian now, the only difference I see is just my religion, the rest is the same,” says Lobsang Dundrup, a middle-class Tibetan in his mid-30s, who runs a local café.

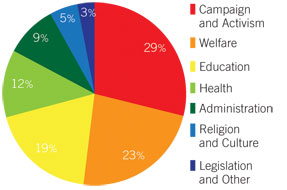

The Dalai Lama established a democratic government in exile, with a prime minister and legislature elected directly by exiled Tibetans in a bid to create enduring social and political institutions for exiles (see box). Tibetan exiles receive a renewable two-year residency permit from the Indian government, which, after securing visa clearance from the Foreign Registration Office in Lower Dharamsala, also permits them to travel overseas. There is growing, unspoken anxiety over the future of Dharamsala and the Tibetan independence movement after the Dalai Lama, who is 74. There is no question that once Tibet’s most iconic figure retires or departs, Tibetan Buddhism will change dramatically and the Tibetan cause could fade from the international spotlight. Many Tibetans are resting their future hopes on the third highest Lama in the Tibetan Buddhist hierarchy, 23-year-old, 17th Karmapa Lama Ogyen Trinley, who was born and raised in Tibet, but escaped to India in 2000 in a dramatic trek that took him across Nepal to Dharamsala.

Alhough the exiles fear talk about the succession, the Dalai Lama himself has not shied from the subject: “If people feel that the institution of the Dalai Lama is still necessary, then this will continue.” He has speculated about the possibility of appointing a new Dalai Lama during his lifetime or even a female Dalai Lama, both of which will break tradition. But the Dalai Lama said: “The point is whether to continue with the institution of the Dalai Lama or not. After my death, Tibetan religious leaders can debate whether to have a Dalai Lama or not.” There is widespread apprehension that when a new, reincarnated Lama assumes the position of the 15th Dalai Lama he may be targeted by China as occurred with the Panchen Lama, the second highest Lama, who was kidnapped by the Chinese government in 1995 shortly after he was named to the post by the Dalai Lama and whose whereabouts still remain unknown. The uncertainties over Tibet and their future notwithstanding, Tibetan exiles in Dharamsala have managed to more than survive: they have created a mini Tibet in exile, which in many ways is more Tibetan than the occupied homeland that eludes their grasp. Photos: Saransh Sehgal

|

You must be logged in to post a comment Login