Arts

In the Land of Gup

It's the season for Indian writers.

|

“Anybody can tell stories. Liars, and cheats and crooks, for example. But for stories with that Extra Ingredient, ah, for those, even the best storytellers need the Story Waters. Storytelling needs fuel, just like a car, and if you don’t have the Water, you just run out of Steam.”

In The Land of Gup, you encounter King Chattergy, the Princess Bathcheat (Chitchat) and Prince Bolo (Speak) and indeed these are the favorite words of desis. Get two or three housewives or bureaucrats or chaprasis across a table with cups of steaming chai and you can have a gossip marathon! Every Indian will remember the stories told by inventive grandmothers and great aunts and family cooks. And who can forget the Amar Chitra Katha comics that brought Hindu mythology into the realm of pop culture? Yet, in spite of a vast reservoir of regional literature, writing in English seemed to be reserved for an anointed few and the names of the well-known writers could be counted on two hands – R.K. Narayan, Raja Rao, Nayantara Sahgal, and Aubrey Menen come to mind. And expatriate Indian writers or those of Indian origin were even fewer – V.S.Naipaul, Nirad C. Chaudhri, Bharati Mukherjee and Anita Desai. English was almost an alien tongue, a legacy of the Raj.

Now it’s a changed world. You can hardly keep up with all the writing in English that’s pouring out of India and its Diaspora! As Anita Desai said in an interview in the Spanish journal Lateral, “It’s become strong in the last ten or twenty years. When I started to write it certainly wasn’t. There was just a few of us who were writing in English; we had a lot of problems in finding publishers, there were very few readers, and no one seemed very interested at all in our work. I think things changed very dramatically – and I can put a date to it: it was 1980 – when Salman Rushdie published Midnight’s Children, and it had such a huge success in the West.” Indeed, Midnight’s Children seemed to break all mental and psychological barriers for Indians wanting to write in English. It was as if the story water taps had been turned on full blast and Indian writers could speak in their own voices. Rushdie had invented almost a new language, an English that was more outsized and outrageous than the original, an English that was an Indian language. It was an English hammered and melded in street smarts and darkened cinemas, the sounds of the bazaar and the contemporary cacophony of India.

Around this time came Vikram Seth’s The Golden Gate, a unique voice – an entire novel in verse that had nothing to do with India. The success of both these books in the west set the stage for the big boom in Indian writing. Amitav Ghosh, Rohinton Mistry, Pico Iyer, Amit Chaudhuri, Shashi Tharoor, Vikram Chandra, Kiran Desai and Upamanyu Chatterjee were some of the star writers getting enormous advances, bagging big prizes and creating buzz from London to New York to Bombay. Midnight’s Children won the Booker Prize and also the Booker of Bookers, Vikram Seth won the Booker for A Suitable Boy and Arundhati Roy for The God of Small Things. Then came Jhumpa Lahiri’s Pulitzer for Interpreter of Maladies and then of course the Big One, the Nobel Prize for Literature awarded to Sir V.S.Naipaul. This year Arundhati Roy was awarded the US-based Lannan Foundation’s annual $350,000 Prize for Cultural Freedom. In India there’s been a virtual explosion of Indian writing in English. Pankaj Mishra, Raj Kamal Jha, David Davidar, Shashi Despande and Sunil Khilnani are just a few of the names being courted and published in east and west. In some ways it doesn’t even matter where people are living anymore, as globalization has erased literary national boundaries. Bombay, London, New York are all just a flight away and the Internet has ensured that geographical boundaries are just that.

English writing has flowered in the Diaspora too and Indian writers in the U.S., Canada and U.K. have made significant contributions from Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni to Akhil Sharma to Manil Suri. Divakaruni, who won the 1966 American Book Award for her very first book Arranged Marriage, has become a household name with a strong following. Her books Mistress of Spices, Sister of My Heart and Vine of Desire have all been well received and she recently stepped into young adult territory with her book Neela: Victory Song. Banking’s loss was literature’s gain and his first book of short stories was Swimming Lessons and Other stories from Firozsha Baag. His first novel Such a Long Journey was short listed for the Booker Prize and won the Commonwealth Writers Prize for the best book of the year; A Fine Balance was a Booker Prize finalist and Family Matters was also longlisted for the 2002 Booker Prize.

Akhil Sharma’s novel, An Obedient Father bagged the Ernest Hemmingway Foundation/PEN award. London-born journalist Hari Kunzru was named “Young Travel Wrtier of the Year” by the Observer. His very first novel turned him into an international star and got him one of the biggest advances. Manil Suri, a professor of mathematics in the University of Maryland, made a stunning debut with the critically acclaimed Death of Vishnu, which bagged scores of prestigious prizes and was released in 23 editions worldwide. The list of South Asian American writers includes Meena Alexander, author of several books including Fault Lines; Anita Desai’s daughter Kiran Desai, whose debut novel Hullaballoo in the Guava Orchard heralded an idiosyncratic new voice; Bharti Kirchner who successfully moved from being a cookbook author to a novelist, with three successful novels to her credit, Sharmila’s Book, Shiva Dancing and Darjeeling.

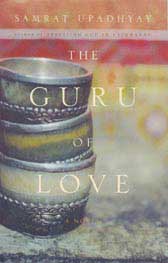

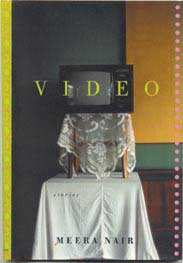

The list of noted young writers continues to grow with names such as Suketu Mehta whose non-fiction book on Bombay and Alphabeth, a novel are both to be published this Spring; Mira Kamdar, at the Policy institute of the New School, wrote Motiba’s Tattoos, a poignant memoir of her Gujarati family roots, which was very well received. Recently Brooklyn-based writer Meera Nair received instant fame with her debut book of stories, Video Nights. Just this year readers were introduced to a wonderful new voice, Samrat Upadhyay, a Nepalese writer whose debut novel The Guru of Love was just so seductive that it was a temptation to read the entire book at one sitting. Another recent noteworthy first book was Monsoon Diary by Shoba Narayan, an engaging memoir with recipes. Indians writers are also moving up the food chain to the screen. Last year Merchant Ivory Productions made a film out of V.S. Naipaul’s The Mystic Masseur (Merchant had earlier made In Custody from Anita Desai’s novel). A made for TV film, directed by Mira Nair, was also made out of Abraham Verghese’s book, In My Own Country. A film has also been made of Rohinton Mistry’s Such a Long Journey and Bapsi Sidhwa’s novel Cracking India was made into Deepa Mehta’s ‘Earth.’

As if awards and critical acclaim (not to mention world-wide notoriety as the world’s most famous exile and fatwah-holder) were not enough, Salman Rushdie reached another distinction this year: His book Midnight’s Children was made into a play by the Royal Shakespeare Company and after a successful run in the U.K., was brought to the United States in association with Columbia University and the University of Michigan. Rarely has a book been given such an honor for the play was accompanied by a month long Midnight’s Children Humanities Festival with artists, writers and scholars coming together to discuss the ideas embedded in the book. All these multiple success stories seem to have certainly stirred up something in the Diaspora – in this universe of physicians and engineers and software technicians we are suddenly seeing so many more new writers emerging. Indian names seem to be on all sorts of books. Just this past year there have been books by first time authors like Tanuja Hidier Desai, whose young adult book, Born Confused was critically acclaimed. Recently Monica Ali, a Dhaka-born writer, was selected for the literary magazine Granta’s “Best of Young British Novelists.” It features her Dinner with Dr. Azad, along with works by Hari Kunzru and Zadie Smith. As Arul Louis, an editor at Daily News notes, “This selection often portends literary fame – at least in Britain. Salman Rushdie, Shiva Naipaul, Martin Amis, Ben Okri, Kazuo Ishiguro and Hanif Kureishi are among those who made the Granta selection in their youth. Therefore, Ali’s first novel, Bricklane, is causing a buzz in Britain.”

Nor are Indian writers limited to fiction – although nonfiction sometimes reads more like incredible fiction, given the state of the world! Pick up any journal and you’re bound to see the name of Fareed Zakaria; switch channels on TV and you’re bound to see his face. Zakaria, the editor of Newsweek International, is a media star whose latest book The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad is making waves; then you have Shashi Tharoor and Pico Iyer, two remarkable writers who segue from fiction to non-fiction with grace. Tharoor, the author of The Great Indian Novel and Riot is also the author of India: From Midnight to the Millennium which was on Bill Clinton’s reading list before his India trip. Pico Iyer, who has delighted readers worldwide with his insightful travel books, is also the author of beautiful novels including Cuba and the Night and Abandon. And then of course, you have Deepak Chopra, a virtual one-man conglomerate with his best-selling books, audios and lecture circuit. Surely such major success stories will propel young writers into the field of non-fiction too. So what’s happening now on the writing scene and how have all these success stories impacted emerging writers in the Diaspora? Is the boom in South Asian writing continuing or is it on the wane? Little India spoke to a number of people in the know to find out what’s happening.

Una Chaudhuri, Professor of English at New York University, says, “There’s been a steady stream of novels and short stories and there are some writers who are well established so they have a presence which South Asian writers just didn’t have before. There’s definitely a difference now; there’s more of a sense of mainstreaming than being this new phenomenon.” She adds, “In the general cultural sphere, beyond the literary production, beyond novels and fiction, I think there is tremendous amount of cultural activity amongst South Asians. The area interests and excites me is drama and theater and I’ve been noticing wonderful new works, new plays, both full length plays and short plays, readings and workshops by South Asian Americans. I’m really impressed by the quality and the engagement as well as the quantity of this writing.” Young South Asians in America seem to be confronting their hyphenated identities and their splintered worlds and many are expressing these issues through the written word. Says Chaudhuri, “I think that’s a sign of it being a young person’s field. They say that people always start out by writing their own autobiography – that you have to get your own life out of your system before you can move on to other subjects. I guess the first books are often focused on people’s own experiences and often those experiences are of dislocation and that seems to be a big theme. I think that’s really opened up and has its own vocabulary and its own linguistic style.”

These young writers have grown up here and so really they are talking about America, their America that embraces their roots and their parents’ past. Observes Chaudhuri: “They are often keenly aware of the Indian cultural background. I’m sometimes amazed at how much seriously and deeply connected some of these younger writers are to issues of Indian identity, history and culture, because they have received them in a more purified way, either by reading about them or through parents.” She points out that the younger generation is also bringing home their close connection to American culture and in a sense educating their parents and changing their parents’ perceptions and making them more open to non-traditional career choices like literature and theater. And of course, big wins by writers like Jhumpa Lahiri make it more permissible to work in these fields! However, there are many complex reasons for the explosion of Indian writing in the west, and one is surely the more hospitable environment. “It’s part of American identity politics; there’s been this multicuturalization of mainstream American culture and African-American and East-Asian Americans kind of led the way and there were successes like the Joy Luck Club,” says Chaudhuri. “It’s also now become a very mainstream concern. This whole concern with mixed identity and hybridism and dislocation. Publishing houses are also open to these new voices, voices other than the Middle American, Anglo white experience.”

Anna M. Ghosh, of Scovil Chichak Galen Literary Agency, has seen an increasing number of books by Indian writers coming across her table. She works on a wide variety of books and recently sold Kathleen Cox’s Vastu Living and is currently working with Thomas John, the acclaimed Indian chef of Mantram, a Boston restaurant, on a cookbook. “I seem to get a lot of query letters from Indians regarding all kinds of books – science, history, politics, how to get into graduate school,” she says. “It’s a whole range of topics and they are not necessarily writing about India at all; they just happen to be Indians who are writing books. I’ve found many of them to be very accomplished, and they’ve got very good credentials. ” Ghosh recently worked with Madhusree Mukerjee on The Land of Naked People: Encounters with Stone Age Islanders. She is also working with journalist Chitra Raghavan, who has written several cover stories for US News & World Report, on her book about the Secret Service. Ghosh, however, has not seen Indians writing genre fiction like mysteries or romances, though she thinks science fiction would be a particularly good field to tackle: “I always think it’s a very rich area for an Indian author or someone from an Indian background. We have a rich tradition of gods and goddesses and all kinds of epic drama. I loved it as a child, reading all the Amar Chitra stories. I think it’s an opportunity for someone to mine.”

How difficult is it to find an agent especially if the writer is not known? “It’s extremely easy if you have something that agents want,’ explains Ghosh. In fact, you’ll be fighting off agents if you’ve got something that is really desirable. If you’ve got something that is really not publishable or is difficult to publish then it’s going to be very, very difficult. Of course, sometimes you just have to find one person with a vision for it – someone who can see the potential.” She also recommends researching the publishers who would be suitable, since publishing houses run the whole gamut from highly specialized to general houses to the academic university presses. If it’s a book about multiculturalism or feminism, it might be a good fit for a university press and indeed some of these houses also print fiction and may not be as competitive as the big houses such as Random House or Simon and Schuster.

There are many new small publishing houses too such as the N.J. based Silicon Press which recently published Bell Labs: Life in the Crown Jewel by Narain Gehani, which documents the metamorphosis at this giant American company; and a work of fiction Fifty-Fifty by Robbie Clipper Sethi, whose first book of short stories, The Bride wore Red was a Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers selection. And then of course, there are many options to self publish now and e-books are another route. Sometimes things just work out in a roundabout way: Ghosh recalls a self-published book that came to her desk just for foreign rights, but she was able to find it a publisher.

And are those big advances that make aspiring writers salivate, still there? Says Ghosh, “You hear of big books; but sometimes those books do well, sometimes nothing happens. A lot of first novels, which are sold for a lot of money, they don’t necessarily ever sell enough copies to ever justify that and that does make it hard for the writer the next time around.”

To aspiring writers, Ghosh says, “Think of what you’re asking people to do, you’re asking them to spend their days and their 25 bucks to buy your book and read it. You want people to read your book and then tell everyone else how much they loved it. So really don’t send it out until you’re sure you’ve put in what it takes. A lot of people feel, ‘Well now’s the time to send it. India is hot, let me be the first person to do it.’ The only people who are going to survive anything is people who’ve got real talent.” Jennifer Hershey, vice president and editorial director at Putnam, is also well aware of the boom in Indian writing. “There may have been a point at which the sheer novelty of the Indian culture and experience was so appealing that books could be published almost purely on that basis,” she says. “Now that it’s become familiar and more books have been published, it’s probably not so much of a phenomenon and is something which has integrated itself into publishing.” Asked if she felt if the big name Indian writers had made it easier for more Indian writers to be published, she says, “I definitely think so, in the same way for a long time African-American women’s fiction wasn’t published and now there’s a lot of African-American women writing. It’s the same kind of thing: some writers break down perceptions within the publishing industry and then it becomes a lot easier for everyone.”

Increasingly, Indian writers are looking to cross geographical boundaries and write past color lines and maps. How easily would mainstream publishing houses accept Indian writing that is not about India or ethnicity? Says Hershey: “The ideal is that you would describe a novelist as a novelist and not as an Indian novelist. That’s the point one should get to and I think we are getting closer to that. I think it’s partly human nature that people are intrigued by cultures that are different from their own, but I do agree it would be nice if we’d get to that at some point.”

Putnam will be publishing For Matrimonial Purposes, the debut novel of Indian journalist Kavita Daswani in June and Hershey has this advice to give to aspiring writers: ” Work really hard to get your book in the best possible shape and then look for a literary agent. You have to be brave and be willing to show it to people and be willing to sometimes experience some rejection before you get to the point where you can find someone that wants to take it on.” All those who loved Manil Suri’s The Death of Vishnu will be glad to know that he’s currently working on the second in the trilogy, The Age of Shiva: “It brings to life the essential characteristics that Shiva is supposed to represent: asceticism, eroticism and destruction, through human characters and events.”

Writers become writers in different ways and as Suri explains about his ambitions as he was growing up, “I liked to write, but no, I didn’t think I would become a writer with a capital W.” Asked as to how easy or difficult it was to get published, he explains, “I was very lucky. I got accepted at the MacDowell Colony (a retreat for writers and artists), where one of the colonists read my first chapter and suggested an agent who he thought would be perfectly suited to my work. He was right. When I sent her the manuscript, she agreed to represent me. She in turn knew which editors to send the manuscript to, and got several publishers interested as a result.”

To aspiring writers itching to get published and cash in on the big boom in Indian writing, he cautions: “Don’t be in too much of a hurry. It’s a luxury to be able to gain proficiency in one’s craft before one’s first book or collection of short stories is published. Today’s competitive market is very unforgiving about anything less than the best you can give.” |

In Salman Rushdie’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories, all tales are derived from the wondrous Ocean of the Streams of Stories in Gup City on the moon Kahani. One can’t help thinking that Indians must be longtime subscribers to the story water supply of this land. Think of all the fantastic tales that have been handed down in the epics and folklore through the great oral tradition in India, the traveling kathakars and kathputliwallas and just the sheer volume of the written word.

In Salman Rushdie’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories, all tales are derived from the wondrous Ocean of the Streams of Stories in Gup City on the moon Kahani. One can’t help thinking that Indians must be longtime subscribers to the story water supply of this land. Think of all the fantastic tales that have been handed down in the epics and folklore through the great oral tradition in India, the traveling kathakars and kathputliwallas and just the sheer volume of the written word.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login