Arts

Banal Dreams

|

Broadway is that great New York institution. Like everything else, and unlike Disney World, it is a mixed bag. There are some shows and some theater. The shows are nothing but a tourist attraction. It is a thing to do along with an expensive meal, a trip around town, preferably with a date of your choice and often a ritual with someone who needs to be courted for one reason or another.

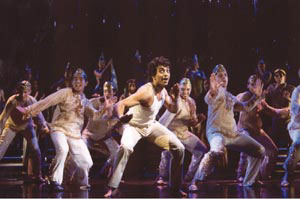

Theater on the other hand, such as it is in the age of mass produced media, is a rare and small art form that thrives in some corners. Theater is self-conscious; Broadway shows are not. The latter are a shameless exercise in showmanship. But some people like it. It is hard to figure out the reaction of the audience to Bombay Dreams. They seem to be responsive, mostly people of European origins. They were laughing, clapping and generally quite engaged with the production. So when one writes about Bombay Dreams, this becomes an essential ingredient. Perhaps Bombay Dreams, that celebrated production that arrived here from the U.K. with inspiration and guidance from Andrew Lloyd Webber and Shekhar Kapoor, serves the needs of tourists. It offers a good example of the kind of showmanship they expect, an exotic stop on their tourist route and perhaps a palatable taste of what we have come to call Bollywood. Bombay Dreams begins with an invocation of the magic of Bollywood. It is a story that promises to be about Bollywood and it attempts to show Bollywood itself. The media publicity raves about the many “special effects,” including a water fountain. It has the components of a Bollywood dream: dance sequences with bouncing flesh, melodramatic twists and turns that are within your limits of expectations, villains and heroes and a measured and mild dose of some social lesson. Yes, it is boy meets the girl story. The girl who bounces around, it turns out, is not the morally desired one, but the one who still believes in Black and White films and whose films do not have happy endings. A.R. Rahman’s score has a crescendo that simply overwhelms the poor Western spectators. It is sufficiently and conveniently cross cultural so as to be placed between belly dancers, Michael and Janet Jackson inspired choreography (which sadly has taken root in Bollywood) and blends the fusion between the Eastern visuals and Western beat. The gifted master sure could do better, but a combination of his populist talents and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s syrupy inspiration leaves this score at the level of the lowest common denominator.

The script and the storyline are meshed with the clichés that even the uninitiated are used to. One of the major breaks in laughter was reserved for a comment by a Hijra that Indian men last longer. Well, they do, don’t they! Sitting through a Bollywood film for two and a half hour certainly means you got to last longer. But it is this hybridity that makes the show a dismal failure. It is neither Indian nor is it anything else. It is a hodge-podge of clichéd, uninspiring lines meshed together to punctuate one dance number from the next. One of the criticisms about the film, Casablanca, it turned out, was one of its biggest compliments. When a critic pointed out that in that film all the archetypes hold a reunion, it was meant to be an insult, a shot at the simplicity and banality of the plot and its dialog. But the film did it so well, it was admirable. One could furnish a similar compliment toward Bombay Dreams except that it is not even a commendable imitation of Bollywood, even for stage. It could easily bring together all the essentials of Bollywood and parade them in a spectacular fashion so as to provide a shock and awe experience to the uninitiated and to the trained. It is a cheap imitation, the kind that our is created at the Bollywood Awards or the kind that you can witness at Nassau Coliseum when some of the stars or their inexpensive look-alikes come to visit.

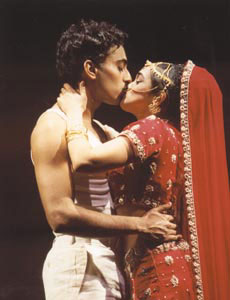

This could have served another purpose, that of a social critique of Bollywood. It could have been a parody, a satire, a self-conscious commentary on the banality or profoundness of Bollywood. The only critique comes in the line that belongs to the protagonist when he says that poverty is made to look beautiful in films. How true! That is a good transition for getting to the Bollywood fare and also the so called art cinema. Alas, the audiences have to look to the some esoteric academic sources to serve that function and that is why it never gets addressed. It becomes clear by the time the intermission arrives why the reviews in mainstream press have been less than glowing, at times deservedly brutal. If the show was a success in the U.K., it has managed to get less of critical acclaim here. And as spectators of Bollywood films know quite well, just because people like something, it doesn’t mean it has to be good. It is instructive, no doubt, that the crowds have seen something entirely different than those who have some critical eye have discovered with great effort. When The New York Times glowed about the “dangerous curves” of Ayesha Dharkar (a major holdover from the London cast), it offered clues. Ms. Dharkar exhibits her ample assets with an untiring energy and an implanted broad smile that cannot be erased. As it turns out, the attractive woman always has a wicked and selfish heart, a lesson in morality that is so common in Bollywood that it should have been offered with some emphasis while we were focused on her curves.

The scope offered by the opportunity to act is limited here as much as it is in Bollywood. But as we know, an average Bollywood film is expected to be saved by the playback singers. When you place that burden on stage actors, it is not an easy calling. Manu Narayan demonstrates this with great ease as he stops short of the demands placed by the ballads and the rocking singing numbers. The saving grace is the character of Sweetie, the central Hijra with a conscience. The common person with a reasoned mind comes from a Hijra community. This motif is used well although to the novices in the audience the script provides little explanation of what a Hijra is and what are they doing in Bombay. The final question one leaves the show with is this: Why bother? In many of the folklorish stories promoted by the arrival of Starbucks culture is the formula of “why bother?” When you order a decaf latte with skim milk, it is often called “why bother?” latte. What can you get with a combination of non-ingredients? Now we know we get Bombay Dreams. The curiosity of the audience may be better served with a Bollywood DVD rental from any of the grocery stores. In fact, a trip to Lexington Avenue or Jackson Heights for the tourist-minded would do more justice. They may not get to see the real curves, but they are not for touching anyway. |

You must be logged in to post a comment Login