Arts

Showtime

|

The theater is a place to love and be loved, to be a child again. And yes, there are samosas too. It is comfort food, like mom’s daal chaval, yields more benefits than a psychiatrist’s couch, and can even bring warring families together. It’s a $5 escape, a three-hour vacation and a culture catalyst. It’s a gathering spot and yes, sometimes, complete strangers have met and fallen in love there.

To top it all, it’s cheap and air-conditioned, good for catching a short nap. It’s also an emotional roller coaster; when you go there, you’re never quite sure whether you’ll end up laughing or crying or both. We’re talking, of course, about the amazing, multi-faceted cinema hall that has been ruling our lives ever since moving pictures were invented. The concept is more than a century old and critics warn that it is beginning to show its age. Videos have come and gone, DVDs may be the newest rage, but cinema theaters, marked for extinction, have got a new lease on life among Indian Americans. As many as 100 theaters screen Bollywood tamashas all over America. Some top grossers like Taal and Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gaam even made it on the Top 20 box office lists in Variety and Hollywood Reporter. “The bigger Hindi films play to a large audience, so the right ones are strong enough to hit the Top 20 on the industry box office charts,” says Gitesh Pandya of Boxofficeguru.com. “Bunty Aur Babli opened at number 16 on the North American charts and Veer-Zaara debuted at number 15. Hollywood studios take notice of this and are impressed with the amount of sales from a relatively small number of theaters.” With the burgeoning South Asian population and new fans from other cultures, the customer base for theaters is growing, and several Indian and Pakistani entrepreneurs have jumped into the fray. From Washington D.C. to Florida, Georgia to California, it is now possible to find a multiplex to see a first run Hindi movie. The theaters have become savvy with colorful websites, online ticketing and a movie hotline to find out where movies are running. Vijay Shah and Gautam Shah of Cine Corp in New Jersey co-own the biggest theater on the east coast, the 13 screen Cine Plaza 13 as well as 15 other theaters in several states.

Says Vijay Shah of the changing theatre landscape in America: “We are having the record number of eyeballs today in the whole overseas market that sees Indian films. North America is the largest overseas market for Bollywood films.” He points out that until a few years ago, distributors would release only five prints in all of North America. Now they release as many as 70 to 80 prints for a hit like Black or Paheli. He estimates that there are about 80-100 theaters showing Bollywood films in the United States and Canada, but only 25 to 30 of these locations show first run, worldwide simultaneous release Hindi movies. “The bazaar starts when the population increases,” says Shah. “Naturally everything starts on a smaller scale. There never used to be a Jackson Heights or an Edison before. There may have been one or two shops, but it all happens when there is a concentrated effort.” For early immigrants, the loss of cinema was almost a familial loss. Can you imagine the pre-video days in an America devoid of any Hindi films? Growing up in the homeland, there were all those wonderful films – the Guru Dutt cinema verite, the Bimal Roy classics and the inane romantic comedies with Shammi Kapoor acting the junglee, and Saira Banu, Asha Parekh and the rest of the brat pack, looking so cool with their sprayed, bouffant hairstyles and their tight salwar kameezs!

There was so much melodrama and so much more bang for your buck in Hindi films that Hollywood films looked quite insipid in comparison and ended far too quickly. You really didn’t seem to get your money’s worth. Growing up in India, time was all one had, so we patronized everything that hit the screen – Hollywood and Bollywood – sometimes even catching two flicks in a day. A Satyajit Ray film like Kanchanjunga in a morning and then a big masala, bodice-ripper in the evening. In the landscape of youth, the cinema hall was the most important structure – and certainly much more appreciated than, say, school. We knew the innards of every theater house in Delhi: where the seats and air conditioning was the most comfortable, where the eve-teasing Romeos were a torment and where you’d get the best snacks. Cinema was a place for family outings as well as sneak fests from college with friends. It was the lodestar of the unending week, and we bought tickets to the new blockbusters in advance or in the black market – for seeing the new offerings the moment they opened was divine. The early immigrants caught Indian cinema at makeshift local halls, often travelling miles for the movie . Often the screening was on campus, such as Columbia University, or in rented theaters. Farooq Khan, who is from Pakistan, recalls that early scene. When he moved to Houston in 1979, there were no commercial theaters showing Hindi movies regularly. He rented a Twin Theater from comedian Jerry Lewis, called it Shalimar Theater and began showing Hindi movies, starting with Muqqadar ka Sikandar, which was a big hit. Theaters screening Hindi movies in those days were far from state of the art, and then came the video boom, putting yet another nail in the coffin of the cinema hall. Khan, like other cinema entrepreneurs in scattered parts of the United States, shut his theater as audiences receded to their homes to watch movies in their living rooms. In 1989, as people rubbed their eyes and finally tired of the videos, he returned to the exhibiting business. He recalls, “I had only 3 screens with a capacity of 600, but the market grew so much that I had to acquire a 6-screen theater in 2004, and I converted it into Bollywood 6, a state of the art theater showing Hindi movies full time.”

Khan, who is a systems analyst by profession, also uses the theater for live cricket match screenings. How viable a business is it? “It depends on each picture,” he says. “It’s a very risky business. Nobody in the world makes more than 10 super hits in a year, max. So in some movies you come ahead and in some you don’t.” He adds: “It is not a business on which you can solely depend, unless you have multiple screens and you can’t afford to have multiple screens like AMC because there isn’t that much product or demand for it. In American films you are dealing with millions of people, whereas here, counting the other South Asian ethnicities, it’s just about one million.” Shiraz Jivani of California has been a movie exhibitor for 16 years – enough time to know the many variables that guide this unpredictable business. He started with Naz, just one small theater with one screen, the first theater in America dedicated solely to Bollywood movies. Today he has three megaplexes in California: Fremont, Yuba City and Artesia. He calls it North America’s First Multicultural Entertainment Megaplex showing movies from India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, China, Taiwan, Korea and Philippines. The theater has 8 screens, Dolby & DTS Sound, 3,000 seats and 5,000 parking spots. He says of the whimsical theater going market: “It’s gone up and it’s come down, it’s gone up and it’s come down. It’s gone up quite a few times and it’s come down quite a few times.” Cine Corp’s Vijay Shah and Gautam Shah have honed the screening of Bollywood movies to a fine art. They operate 13 theaters on a partnership and revenue sharing basis with American chain theaters. These include Manhattan Loews Theater in Times Square as well as theaters in Connecticut, New Brunswick, Burlington, and Cherry Hill, N.J., Philadelphia, Pittsburgh Chicago, and Charlotte, N.C. “We were the first people to put all-Indian movies in mainstream theaters,” says Shah. “They never used to give any screens to Indian people. We were the first ones, because we bought our own multiplex cinemas, the Cine Plaza 13, from Regal Cinemas.” Through Regal the Shahs developed contacts with other chains, started attending trade shows and building relationships within the industry.

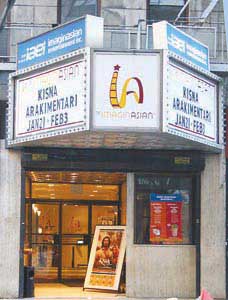

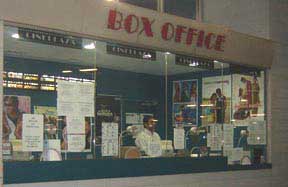

The Shahs studied the demographics in different locations and continued to take on new theaters on this revenue-sharing basis with American chains. Multiplexes in New Jersey, California, Texas and Georgia are finally giving movie-goers a satisfying experience, because small mom and pop theaters have been notorious for poor service and are technically inept – another reason why many South Asians have preferred to watch movies at home. “Most of the Indian theaters are rundown, because they do not have the capital,” says Shah. “Running a multiplex, being a theater operator, being in a people’s business, catering to what people want, and increasing the business – that too in an erratic market like this – it’s difficult.” He says the theater business is an art, unlike most businesses, such as a grocery store. Many theater operators don’t run their business professionally, he says. They do not have computerized ticket systems and sell “raffle tickets,” collecting half the ticket as clients enter. “The theaters don’t have air-conditioning, the shows don’t start on time, the restrooms are really dumps.” He says that many theaters have been closed down by the state or city. “There are so many theaters, which are not run professionally and so don’t draw a regular family or social crowd.” Complaints of movies starting late, musty auditoriums and poor sound systems are legion among Indian movie goers. American downtowns are dotted with abandoned theaters, which have sometimes been snapped up by Indians. Often these new owners don’t have the capital for renovation. “The theater business is nothing but real estate and real estate is nothing but translation of return of investment,” says Shah. “If I have a million dollar property and I don’t get a return of 20 percent – or $200,000 – then it’s not worth running this business. So theaters are dying. If a big chain comes next to a small theater, its days are numbered.” Adds Shah, “If a theater isn’t doing well, it’s dumped. It’s an entertainment business secondary, but real estate first. In Manhattan a theater has less value, but the same place converted into a supermarket or restaurant has more value. A theater is always dependent on a good product, and if you don’t get a good product this year, then you’ll do less business.” For an Indian owned multiplex to survive, it has to also screen American films to succeed. Indian chains find it harder to get first run American movies compared to powerful big mainstream chains, which have a special relationship with the Hollywood studios. It’s hard, for example, to compete with a Loews chain that has 15,000 screens nationwide. Says Shah, “Small moms and pops will get frozen out, because they do need mainstream movies too to survive.” Exhibitors like the Shahs and Jivani are doing their best to capitalize on the strengths of Bollywood by attracting non-traditional audiences, and by also screening other regional, Asian and art films as well as American films on their multiple screens. Their theaters can seat over 3,000 people, and are attracting Indians, Pakistanis, Iranians, Turkish, Srilankan, Bangladeshi, and Afghanis, and some Americans too. The ImaginAsian Theater in Manhattan is perhaps the boldest experiment in reaching different communities and bringing them together for first-run movies, not only from India but also from several Asian countries. Deceptively small and generic looking, it’s probably Manhattan’s best-kept secret. “The ImaginAsian is more than just a movie theater, it is a place where the community can gather,” says Pandya. “We are trying to use the space to spread the word about Asian artists, showcasing artists that wouldn’t usually get seen in other venues in New York City.” But keeping the Bollywood cinemas above water is a constant challenge. Shah, who is an engineer by profession, has taken to the film exhibition business with the zeal of a missionary: “I’ve tried to stabilize the industry here. I’ve put my blood and sweat into it. I’m the janitor there and I’m the dealmaker there. I come home every night at 2 or 3.”

He believes this crazy, chaotic business can be organized, almost engineered, to succeed if done right. Since neither the Indian distributors nor exhibitors have formed trade associations or organizations yet, Shah has been informally establishing a network of theater owners across the United States. “The whole movie business is like the casino business,” he says. “The movies are bought by the exhibitor sight unseen. I might spend $20,000 for the film and in the first week itself the film may crash at the box-office or if there’s piracy on Monday, I’ve lost a lot of money.” He says it may appear that the distributors take the biggest risk, but in fact the biggest risk is borne by the exhibition community, because they take the risk not only for the theater operation, but they also subsidize the cost of the distributor by giving him an advance and a minimum guarantee on the prints, whether the movie performs well or not. “Our employees don’t say, ‘Since you didn’t make money, give us less money this week,’ he says. “Our landlord won’t say, ‘Since you didn’t sell so many tickets this week, Mr. Shah, I’ll give you a break this month.’ Besides the overheads, there are the other variables such as snowstorms, cricket season when no new movies are released in India, Ramadan month, and Navratri, when nobody has time to go to the cinema. He points out that the South Asian population is comparable in numbers in the United States and the United Kingdom, but because of the geographical vastness of America, doing business is far more difficult. He says, “In the UK, they deal only with chain theaters. No Indians own their own theaters except a couple of people. Here mainstream chains don’t want Indian business, because they are dealing with hundreds of millions of dollars in grosses and our business looks like a drop in the bucket.”

The distributors play an important role in moving the product for the theaters. One of the biggest is Yashraj Films, which is both filmmaker and distributor, and has a steady reputation for delivering box office hits. This year alone its roster included such blockbusters as Black, Bunty aur Babli, Kaal and Salaam Namaste. Yashraj Films, which has built up its brand over 45 years, introduces 4-6 films a year in the U.S. market. “The challenge is how we provide viewers facilities which compare with mainstream theaters,” says Jawahar Sharma, head of operations of Yashraj Films. “Of course a lot of improvement has been made and at the end of the day those are the cinemas which form the backbone of our business, because Indian films don’t so far get consistent screen play in American theaters. Over the next few years the concentration has to be on improvement of infrastructure.” Other distributors include Kria Inc., based on the West Coast, which distributed films like Sarkar and Dus recently; the New York-based UTV, a major public company in India, distributors of Mughal-e-Azam and the upcoming The Namesake, and Rainbow Films in New Jersey, which brought in Hungama and Dil Mange More, and the upcoming Garam Masala. By far the largest distributor of movies from India, however, is Eros International, whose biggest hit Devdas was released with 88 prints. Eros distributes 50 percent of the movies coming out of Bollywood, as many as 55 movies annually, some direct to DVD. About half make it to the theater. The company was among the first to start releasing multiple prints. Its recent hits include No Entry, Chocolate, and Dil Jo Bhi Kahe. “The distributor’s role is to ensure that the film is being shown in proper places; otherwise he’s not going to get the returns,” says Ken Naz, CEO of Eros International: “The scene’s definitely changing, because in places which don’t have Indian movie theaters, we are working with big American chains to put our movies in those locations on a sharing business.” He adds: “Some of the declining business is due to the fact that young people are not happy with their cinemas. And one reason is that they are not professionally run in terms of management and service. People want the same atmosphere that they get when they go to mainstream movies: stadium seating, state of the art theaters. Our movies have become technically sophisticated and for that you need proper venue and equipment.” But is the desi moviegoer willing to pay mainstream rates for his Bollywood fix? For, like any masala movie, the story about the desi cinema hall also has a mustachioed villain – the pirate. For every blockbuster film that hits theaters on a weekend, there is usually a pirated DVD copy available for $4 in stores on Monday. “Most Indians are price conscious rather than quality conscious,” says Jivani. “They’ve been watching pirated movies for so long that their conscience doesn’t bother them. They’ve literally killed their conscience! Even the richest Indian man – you go to his house and you’ll see pirated DVDs. We should not hurt our own industry, but we are.” He points out that many desis have an entertainment budget. They watch the Hindi movies on DVD and save their dollars for the mainstream market, watching Hollywood movies in the theater: “This is because of piracy our movies are available on DVD so fast. Hollywood movies are not available on DVD for at least 6 months.” Jivani feels Indian multiplexes will be just a pipe dream until piracy, which he estimates at almost 88 percent of all viewing, is cut down by at least 30-40 percent. “It’s a very, very negative picture. Mangal Pandey opened fantastically in the first week. The second week a good quality DVD was out and it hurt the business a lot. The numbers dropped like a hot potato, sales dropped by 30 percent. To whom can you complain? It’s very sad. Aamir Khan was coming out with a movie after four years. We were hoping for very good results.” Jivani says four years ago he had secured $35 million in private funding to start megaplexes in the United States, but the investors backed out because of piracy concerns. “You cannot do anything about it, because it goes to the root. The loss to the Indian film industry is over one billion dollars a year – and that’s a billion – from piracy.” Theater-owners are trying their best to wean people from their fuzzy, pirated videos with mid-week “buy one, get one theater ticket” offers. Some are luring them with chaat and meals at the theater – for who can resist the poetic beauty of a well-fried samosa topped with tamarind chutney? Vijay Shah has gone all out to hook the Indian moviegoer, if not with Salman Khan and Shahrukh, then with bhel, papdi chaat and vada pav sandwich, topped with mango lassi, coconut juice, guava juice, sugar cane juice and Indian ice-cream and kulfi. All these are served on a 50-foot long concession stand at the Cine Plaza 13, in New Jersey with four computerized stations serving1,500 people at a time. He says, “We’ve also made Americans eat that stuff and they love it!” On the whole, he finds many people are willing to pay the higher ticket and see the movie the way it was meant to be. He says of the immigrant population: “People do spend money now, because they know that this is where they are going to die eventually. They are not going back home again. This is their land. They will go and visit India, but they are here for good.” Having calculated the cost of everything in rupees, are they ready to spend in dollars now? He says, “They know they’ve worked hard and it’s about time they loosened up and started enjoying life.” Complains Shah: “They bring their own food from home. They eat paan parag and tobacco and spit everywhere. I spend so much money cleaning up. I provide stadium seating, rocker lounger chairs with cup holders, which cost me $300 per chair. These are ergonomic chairs that take care of a person’s feet, his back and his comfort. All this comes at a cost, but people don’t want to pay a dollar extra.” Shah provides a behind the scenes peak, as it were, at the movie hall business. He says maintaining a 59,000 sq. foot cinema complex costs big bucks: The Dolby Surround System costs $100,000 and the air-conditioning and heating alone is $10,000 a month. He is charged $3,000 to haul away the garbage that people leave behind: “Whether people come or not, whether good movies come or not, I am bound by these fixed costs.” He says that theater owners are dependent 80-90 percent on Indian business: “It’s not a very rewarding business and the proportion of reward to the risk involved is not very high and that is why you don’t see too many good Indian theaters around, because there’s no support from the trade or the industry.” Yet somehow the desi movie theater survives. Our cinema halls may be the pyramids, the temples and the coliseums of the future, to be peered at by future archaeologists and anthropologists. Indeed, there are already studies on the social values of theaters showing Hindi films and the people who frequent them. Dr Rajinder Dudrah, lecturer in Screen Studies at the University of Manchester, UK, and Dr Amit Rai, Department. of English, Florida State University, are currently embarked on a study: “From the Trafford Centre (Manchester) to Times Square (New York City): Transatlantic Bollywood Cinema Going.” Dudrah is also the author of, “Bollywood: Sociology Goes to the Movies.” Dudrah and Rai looked at UCI Cinema in Manchester, a 24-screen multiplex of which four screens show Bollywood films and in Birmingham they looked at several theaters including one of the biggest, Star City, a 30 screen complex, in which six screens are devoted totally to Bollywood releases. In New York they looked at the small independent Eagle Cinema in Jackson Heights and the more plush Loews in Times Square. Their ongoing study looks at the social ramifications of the cinema hall among Indians in the Diaspora. “There is definitely a sense that Bollywood is arriving on the entertainment landscape,” says Dudrah. “But there is a much longer history that hasn’t been tapped into. In the post war period in the 50’s and 60’s, mainstream cinema halls in London were hired by desis on the weekends. During the week they were working in the factories or largely in the foundries. There were some leisure classes but they were few and far-between and it was really manual laborers. This was a moment for kith and kin, friends and family to get together. “It was also an opportunity for some of the desis who were having problems with immigration, housing or racism, to talk with others. Certainly in the UK there was a history of post war cinema going which was tied to community formation. In the US there were such stories but they were more sporadic. In the UK it’s much more compact geographically while in the US the desi populations are much more spread out.” Rai and Dudrah found a class demarcation in desis who were able to afford the Times Square economy: largely Manhattanites and those who traveled from the suburbs, hanging out in Manhattan. They would pay $10 to watch the same film that was showing in Queens for half the price. “They would come out in the razzle dazzle, in the multinational brand name culture of Times Square while the Eagle Theater in Queens was more tied to the desi community, to the mango stands, the groceries and chat shops. Dudrah and Rai recall meeting a woman in the Eagle Theater who told them, “I always carry a box of tissues to wipe down my seat.” Even the overheard conversations in the two theaters seemed to be different: Listening in, after showings of the Hrithik starrer Koi Mil Gaya, they found that in the Eagle Theater, the moviegoers would be discussing the fact that Hrithik was the son of Rakesh Roshan in a very familiar, familial way while in the Times Square theater the conversations were more about the analysis of the film. The theater is a meeting place, a place to chill out and travel back to India without actually boarding an airplane. “When you go to my lobby you feel you’re in India,” says Jivani. “You drink Indian tea, you eat bhel puri, papdi chaat and samosa; you don’t get the same ambience in the mainstream theaters ” Jivani says Naz 8 has become a social hub, a meeting spot and gives the example of two families, one from Concord and the other from San Jose who meet at the cinema on the weekend, a halfway destination to catch up on old acquaintances. They watch the movie, chat and have dinner together. It’s a self-contained complex: one can probably catch a movie, meet a suitable boy and get married on the same day, accomplishing three quintessentially Indian things in one place! Hamid, a PepsiCo network architect, says Fun City is a community collaboration where people from different South Asian countries, the mainstream as well as from different religions, have joined together: “It’s more like a community project than a one person project.” He says: “I think the future is very bright. Since DVDs, the life of the movie has gone down, but because of the quality of the movies now, movies in the first and second week, especially before the DVDs come out, have done well. This summer has been a great summer. We’ve had at least ten big hits.” Says Boxoffice Guru’s Pandya: “This summer has been pretty strong for theaters playing Indian films like Bunty Aur Babli and Mangal Pandey. It’s probably the strongest the Bollywood box office has been in a few years. But the business is very star-driven so when Shah Rukh and other A-list stars don’t have films for a while, business can get depressed as people are used to just waiting for DVDs for mediocre films.” Of course, one can never predict the future and as fancy new hi-tech gizmos appear, the cinema hall remains endangered. Says Pandya: “Hi-tech home theater equipment is threatening to take away sales from movie theaters for all types of films, not just Indian ones. Ticket prices rise each year and many moviegoers are finding that they can wait a little and equally enjoy a film at home with their home theaters. But the event films will still attract large crowds to theaters since there is an urgency factor there.” He says, “I have put together a 16-speaker, 135″ home theater with picture and sound quality that would rival the best theaters in the country. I have even added seat shakers (they call them butt-kickers), which actually vibrate the seats when Clint Eastwood fires his Magnum.” He recalls watching the Guru Dutt classic Pyaasa on DVD often, but watching it on his giant screen was a totally different experience. In the large format, the characters did become larger than life and more intense, and had Shukla and his wife teary-eyed. While he’s delighted with the high quality of his home theater, even he ends up going to the cinema hall for first run movies. Others feel the home theater cannot compare with the multi-faceted cinema hall experience, where nostalgia, memory, pleasure and companionship all mingle. “Every house has a kitchen, some have great kitchens,” says Jivani. “But you know, people do need to go out and everyone needs an outing. Being Indian we cook at home, but we love to go to restaurants once in a while. I don’t think anything we see in a home can replicate what we see in the theater.” Indeed, the desi love affair with Bollywood cinema is eternal, reincarnated through cycles of birth and rebirth, and the cinema hall is that enchanted spot where it all happens. Not on video, not on DVD, but in the dark, lush expanse of a huge screen surrounded by Dolby Sound. |

You must be logged in to post a comment Login