Over the past decade, both the United States and Europe have made major strides in reducing their greenhouse gas emissions at home. That trend is often held up as a sign of progress in the fight against climate change.

But those efforts look a lot less impressive once you take trade into account. Many wealthy countries have effectively “outsourced” a big chunk of their carbon pollution overseas, by importing more steel, cement and other goods from factories in China and other places, rather than producing it domestically.

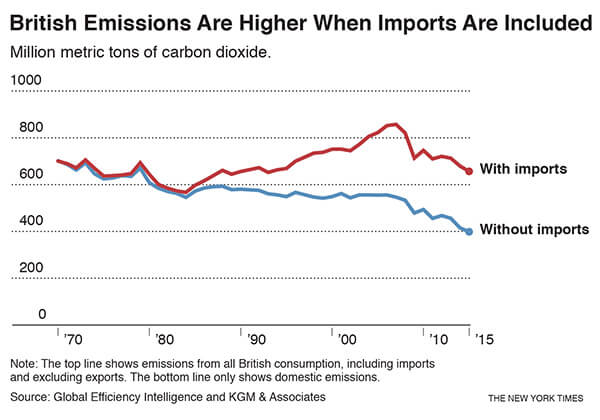

Britain, for instance, slashed emissions within its own borders by one-third between 1990 and 2015. But it has done so as energy-intensive industries have migrated abroad. If you included all the global emissions produced in the course of making things like the imported steel used in London’s skyscrapers and cars, then Britain’s total carbon footprint has actually increased slightly over that time.

“It’s a huge problem,” said Ali Hasanbeigi, a research scientist and chief executive of Global Efficiency Intelligence, an energy and environmental consulting firm. “If a country is meeting its climate goals by outsourcing emissions elsewhere, then we’re not making as much progress as we thought.”

Hasanbeigi is an author of a new report on the global carbon trade, which estimates that 25 percent of the world’s total emissions are being outsourced in this manner. The report, written with the consulting firm KGM & Associates and ClimateWorks, calls this a “carbon loophole,” since countries rarely scrutinize the carbon footprint of the goods they import.

That may be changing. Last fall, California’s lawmakers took an early stab at confronting the issue by setting new low-carbon standards on the steel the state buys for its infrastructure projects. But dealing with imported emissions remains a thorny problem.

Some environmentalists see it as the next frontier of climate policy.

Game of Whack-a-Mole

The new report, which analyzes global trade from 15,000 different sectors — from toys and office equipment to glass and aluminum — builds on previous academic research to provide one of the most detailed pictures yet of the global carbon trade.

Not surprisingly, China, which has become the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide, remains the world’s factory. About 13 percent of China’s emissions in 2015 came from making stuff for other countries. In India, another fast-growing emitter, the figure is 20 percent.

The United States, for its part, remains the world’s leading importer of what the researchers call “embodied carbon.” If the United States were held responsible for all the pollution worldwide that resulted from manufacturing the cars, clothing and other goods that Americans use, the nation’s carbon dioxide emissions would be 14 percent greater than its domestic-only numbers suggest.

Between 1995 and 2015, the report found, as wealthier countries like Japan and Germany were cutting their own emissions, they were also doubling or tripling the amount of carbon dioxide they outsourced to China.

Under the Paris climate agreement, countries are held responsible only for the emissions produced within their own borders. Experts have long debated whether that makes sense. Is it unfair that China and India are blamed for emissions that occur because they’re making goods for richer nations? What about the fact that they also benefit from having those factories and jobs?

The migration of industries like cement and steel overseas can also shift production to less-efficient factories governed by looser pollution rules. An earlier study that Hasanbeigi led at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory found that China’s steel industry, on average, emits 23 percent more carbon dioxide per ton of steel produced than U.S. and German manufacturers do. One big reason? China’s power grid relies more heavily on coal.

Since the financial crisis in 2008, however, the outsourcing of emissions from wealthy countries to developing countries has started to slow. More recently, much of the growth in carbon outsourcing is occurring between developing countries, according to a recent study in Nature Communications.

“Just as China’s starting to deal with its emissions, it’s been pushing some of its more carbon-intensive activities into countries like Cambodia, Vietnam and India,” said Steven Davis, a scientist at the University of California, Irvine and co-author of that study.

“From a climate policy context,” he added, “it’s like a game of whack-a-mole.”

The Unlikely ‘Tax’ Solution

One possible solution to all this emissions shifting would be for all countries to work together to enact a global carbon tax that applied equally everywhere. But in the real world, that is unlikely to happen anytime soon. And, while some politicians like President Emmanuel Macron of France have suggested that Europe put its own carbon tax on imported products, that idea has not gained traction.

So some policymakers are exploring other ideas.

In October, California enacted a “Buy Clean” law that requires steel, glass and other materials used in public works projects to meet certain low-carbon standards. The law came after a controversy over the refurbishing of San Francisco’s Bay Bridge, when the state bought steel from a heavily polluting Chinese mill instead of from cleaner facilities in California and Oregon.

California’s law may initially favor domestic producers — which helps explain why it was supported by some steel companies and the United Steelworkers. And environmentalists hope that, in the long term, the policy could have a ripple effect worldwide.

“California can’t go regulate factories in other parts of the world,” said Kathryn Phillips, director of the Sierra Club’s California chapter. “But we can say, if you want to do business with us, the world’s fifth-largest economy, you have to do what you can to reduce emissions.”

Lawmakers in Washington state recently requested a study of “Buy Clean” standards for their state, and a similar bill was introduced in Oregon’s last legislative session. But the idea can be contentious: In California, the cement industry fought hard to be exempted from the rule. Steel and cement production worldwide each account for about 5 percent of global emissions.

The construction industry is also starting to take an interest in the carbon footprint of the materials it uses. The U.S. Green Building Council, a nonprofit that certifies buildings as “green” under the LEED label, encourages environmental disclosures for a variety of building materials like cement or glass. A new round of LEED standards, currently in development, could go even further by urging low-carbon standards.

Chris Erickson, the chief executive of Climate Earth, a firm that helps companies assess the environmental impact of their supply chains, says that even transparency can be eye-opening. His company built a searchable database of different concrete mixes that are available, allowing architects to seek out materials that have, in some cases, a carbon footprint that is one-third of the industry average.

That, in turn, could put pressure on suppliers to lower their emissions. “Even for companies who don’t want to admit it,” Erickson said, “they know a change is coming.”

© New York Times 2018